Your Brain craves Protein (Patreon)

Downloads

Content

</figure>

</figure>I just released article #2 about protein titled You’re not too fat, you’re under-muscled where I present the idea that we should focus more on having healthy muscle more than having tunnel vision on losing fat. For this third protein-focused article, let’s talk about protein, muscle and exercise’s benefits on alertness, mood and the brain in general. I’m mixing the three together because as discussed in the last article, higher protein intake generally suggests more muscle mass and of course exercise means more healthy muscle.

<figure> </figure>

</figure>Ample protein appears to be really important for the brain. I recently posted this study above finding an association between protein intake and reduced risk for depression. Another 2020 study concluded that “total protein intake and protein intake from milk and milk products might reduce the risk of depressive symptoms in US adults.”

Of course we eat protein for the amino acids it contains, and those amino acids are are important precursors of neurotransmitters, especially in the brain. As just one example, maybe you’re aware of the amino acid tryptophan being the precursor to serotonin. A small study analyzing subjects who slept at a sleep lab found that those who ate protein rich in the amino acid tryptophan were more alert in the morning likely due to improved sleep quality. With that in mind, how does protein consumption play out for people’s brain function as they age?

<figure> </figure>

</figure>According to a March 2020 study:

Compared with the healthy elderly, patients with dementia have significantly lower protein intake and lower protein intake of patients with dementia is reported to be associated with severe dementia.

Drawing on multiple papers the authors of that 2020 study explain:

Nutritional epidemiology has shown the importance of protein intake for maintaining brain function in the elderly population. … The levels of protein intake in aged people are positively associated with memory function , and elderly people with high protein intake have a low risk of mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Moreover, elderly people with high protein intake have recently been reported to have low amyloid β accumulation in the brain.

Subscribed

On the flip side, there are multiple studies like this one from 2018 that find an association between lower cognitive functioning and lower muscle strength and muscle mass.

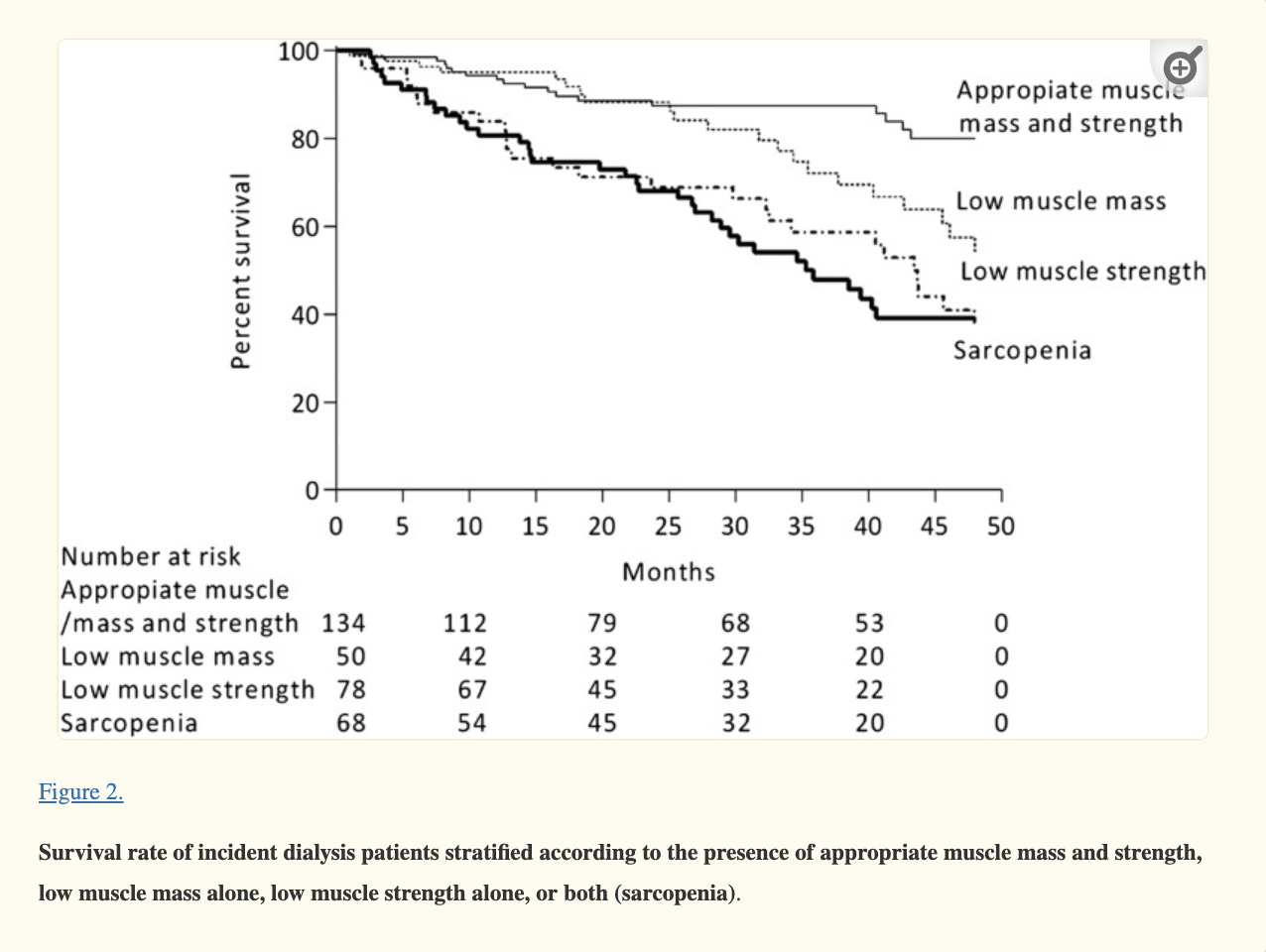

<figure> </figure>

</figure>This study interestingly demonstrated that patients on dialysis with more muscle mass had significantly higher rates of survival.

A clinical trial even found that snacking on high protein foods in the afternoon “improves appetite, satiety, and diet quality in adolescents, while beneficially influencing aspects of mood and cognition.” A 2021 study out of China found that kids on a higher protein diet had better math scores.

<figure> </figure>

</figure>I would be really interested to see some studies on the effect of diets with differing macronutrient compositions on pro gamers’ performance. People competing at that level are operating at the peak of (a specific type of) mental fitness. There are very few gamers past the age of 31 and a study from PlosONE titled Over the Hill at 24 suggests that once you hit 25, you’re pretty much too old to be a pro gamer because that is when reaction times start to wane. Maybe gamers would benefit from a more protein-rich diet.

Subscribed

A randomized control trial looking at the “effect of a high protein meat diet” on cognition found those people in the group getting the high protein diet “improved their reaction time significantly” compared to the “usual” protein diet group. Maybe gamers themselves have already picked up on the importance of protein … considering an 2023 article titled What Do Gamers Eat? alleges that gamers eat “too much meat,” according to a 2021 German study.

One other important aspect of day-to-day cognition is your level of alertness. You might have an IQ of 135, but if you need a coffee to wake up, a coffee to get through the post-breakfast slump, another coffee to get past the post-lunch slump and another coffee to get past the midday slump, maybe your brain isn’t performing so well. There’s a lot of factors to a situation like that, but when it comes to protein, one thing you should know about is a neuropeptide called orexin.

<figure> </figure>

</figure>Protein, Alertness and being Tired all the time

Almost 2 years ago, I made a video titled Why you’re always tired where I talk about the orexin neuropeptide system and how in general you can expect things that increase orexin signaling to raise alertness. Unsurprisingly, things like exercise, caffeine, fasting, low carb diets and weight loss all increase orexin signaling. Personally, I’ve found when I eat just a bit too many carbs, it reliably makes me tired and a ketogenic diet or fasting reliably gives me more stable energy.

I did mention in that video that not only do dietary amino acids themselves stimulate action of the orexin system, but if you eat ample protein with your carbs you can lower the alertness blunting effect of those carbs.

<figure> </figure>

</figure>One thing I didn’t point out in that video is how protein’s influence on hormones leads to greater orexin signaling. To make this simple, insulin and glucagon are two hormones in the body that kind of have opposite functions. Insulin makes you store energy from food, glucagon helps you burn food for energy. Higher levels of glucagon are associated with more alertness, and ingesting more protein leads to a greater secretion of glucagon.

A 2011 randomized trial on undergraduate students demonstrated positive short-term effects of a high-protein breakfast on mood while enhancing vigilance and decreasing distractibility.

When you feel like you need another coffee NOW to peel you off of the floor, you could try eating a hunk of lean protein first. Ingested proteins elevate amino acid levels in the blood and brain on a time scale of tens of minutes.(S)

According to Eat, seek, rest? An orexin/hypocretin perspective:

“Intragastric infusions of dietary-relevant mixtures of non-essential amino acids evoked a slowly building excitation of [hypocretin/orexin neuron] population activity, which peaked 10s of min after the injection.”<figure>

</figure>

</figure>The Brain craves Muscle and Exercise

Contracting the muscle is a major source of neurotrophic factors.

Neuro meaning “brain” and trophic meaning “growth.” So, muscle contraction produces ‘brain growth factors’

This paper explains that “the literature suggests that sarcopenia and cognitive decline share pathophysiological pathways,” meaning that the process that is having older people lose their muscle … is also degrading their brain.

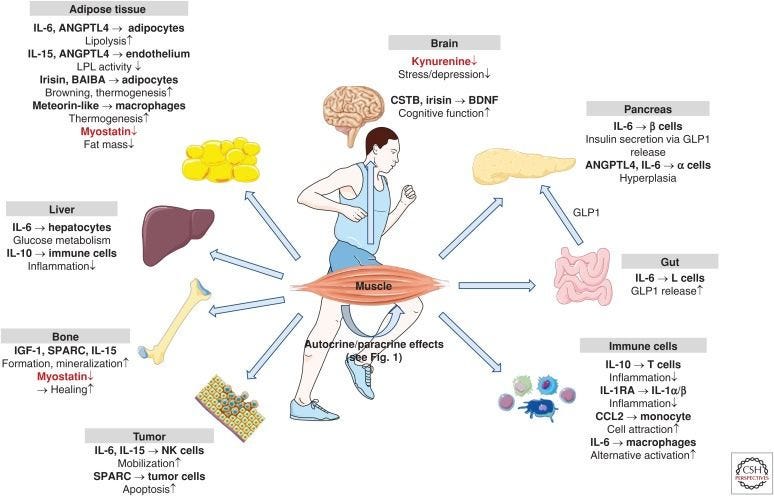

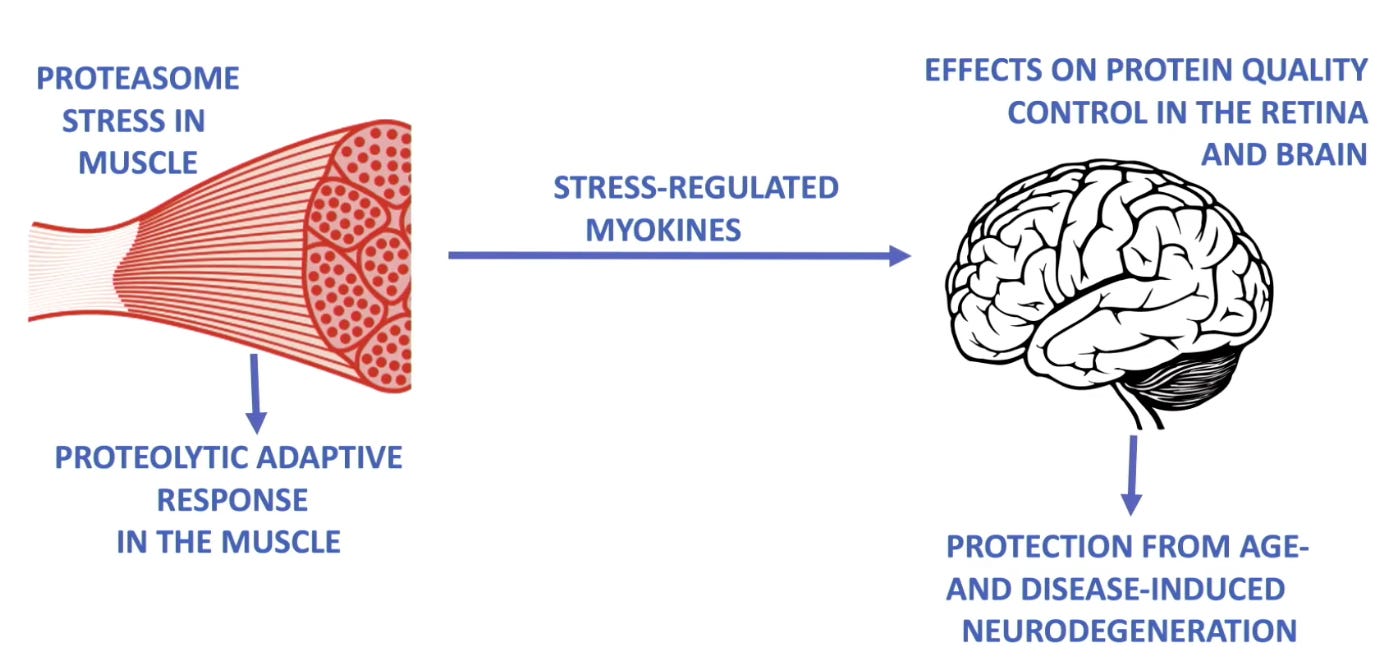

What many people don’t realize about muscle is that it’s not just a bunch of rubber bands that get bigger when you lift weights - the muscle is an endocrine organ. Stimulating the muscle with exercise facilitates the release of proteins called myokines that have endocrine and cell-signaling functions. Myokines are fantastic for health - they help you regulate your weight, lower your inflammation and even improve cognitive function.

<figure> </figure>

</figure>Dr. Fabio Demontis gave a talk titled Myokine-based interventions to contrast muscle and brain aging where he presents yet another way exercise is good for the brain (and eyes).

<figure> </figure>

</figure>His work shows quite simply: Exercise is a stress on the muscle and, as a result of the muscle responding to this stress, myokines are released. These myokines have the eventual effect of protecting the retina and brain from aging.

<figure> </figure>

</figure>In a September 2016 issue of TIME Magazine, Dr. Mark Tarnopolsky said:

“If there were a drug that could do for human health everything that exercise can, it would likely be the most valuable pharmaceutical ever developed."<figure>

</figure>

</figure>In his lecture The Real Reason for Brains, Neuroscientist Daniel Wolpert says:

“we have a brain for one reason and one reason only and that’s to produce adaptable and complex movement. There is no other reason to have a brain.”

He illustrates this with the example of a sea squirt. Early in its life, the sea squirt has a nervous system that allows it to move around so it can find a nice rock to attach itself to. Once it achieves that, it will spend the rest of its life there, with no need to move. So the first thing it does after it arrives at the rock is it digests its brain for energy. Maybe brains like it when we justify their existence by moving our bodies around.

<figure> </figure>

</figure>Dr. John Ratey wrote a book called Spark that explains all the ways exercise is good for the brain. One mechanism highlighted in the book is how exercise encourages the secretion of Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor. Neuro- means “brain” and trophic means “growth.” John Ratey calls this brain growth factor miracle-gro for the brain because it literally makes the brain grow.

Ratey writes in his book that:

Early on, researchers found that if they sprinkled BDNF onto neurons in a petri dish, the cells automatically sprouted new branches, producing the same structural growth required for learning.

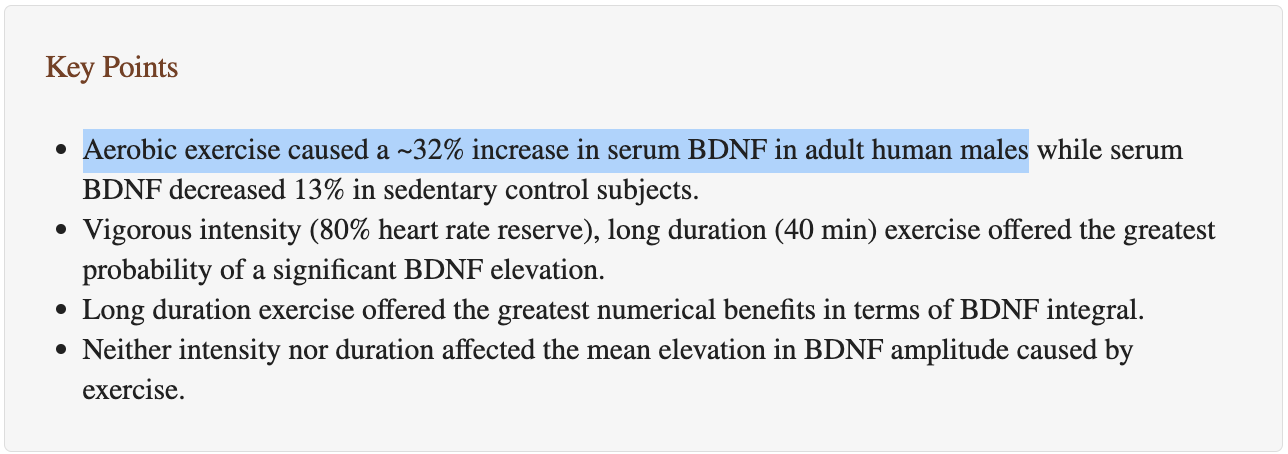

A 2013 study in the Journal of Sports Science and Medicine found that just 20-40 minutes of aerobic exercise increased BDNF in the blood by 32%.

<figure> </figure>

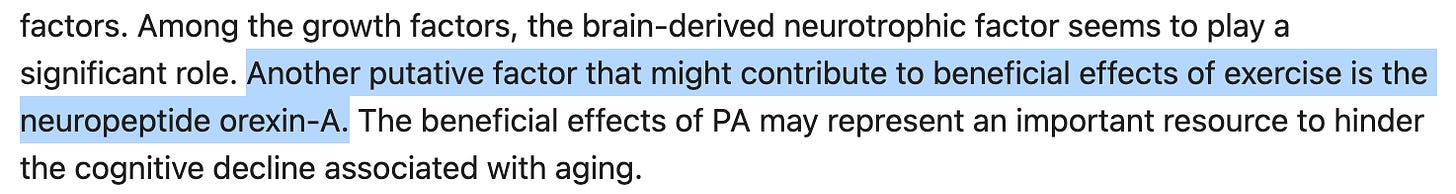

</figure>Another study says that many of the beneficial effects that come from exercise may be due to exercise’s connection to orexin-A, that neuropeptide we discussed earlier.

<figure> </figure><figure>

</figure><figure> </figure>

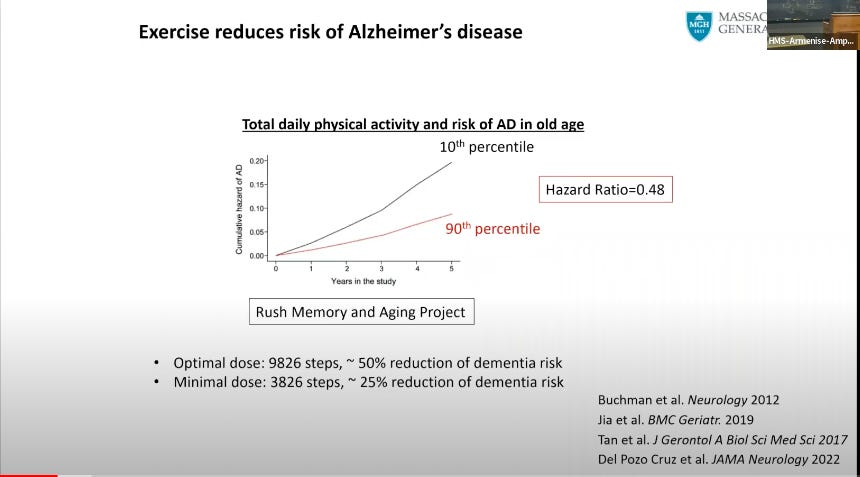

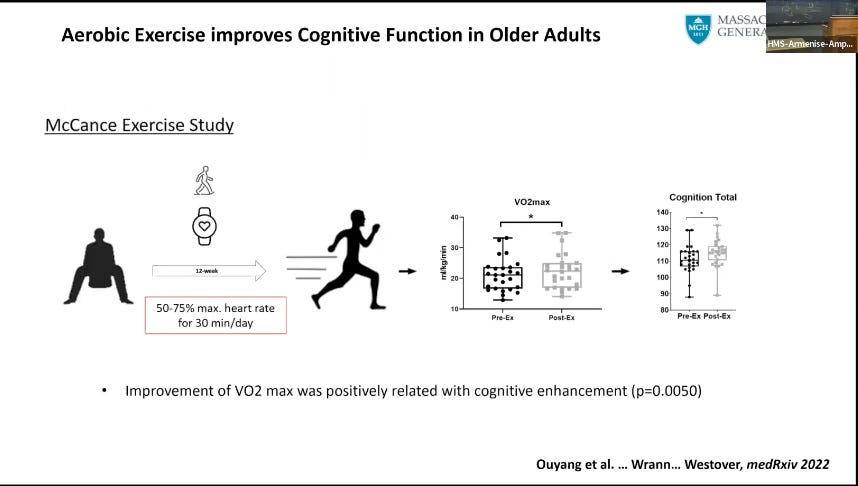

</figure>In a presentation of Dr. Christianne Wrann’s, she presents data showing that walking just 10,000 steps a day cuts your risk for dementia in half. Exercise being fantastic for the brain and for healthy brain aging is very well established. Dr. Wrann’s presentation outlines many of the ways exercise, particularly aerobic exercise is good for the brain, but if you’re interested in the basics I’d say this presentation by John Ratey is a better place to start.

<figure> </figure><figure>

</figure><figure> </figure>

</figure>Isn’t protein bad for longevity?

Despite the various data showing better cognitive performance and better health outcomes for elderly people with more protein, David Sinclair (among others) has popularized this idea that restricting protein makes you live longer because it reduces activation of something called mTOR. This mTOR is basically a signaling pathway that encourages growth and there are some papers that suggest that reducing mTOR activation increases longevity in certain non-human organisms in the lab. So, to live longer, David Sinclair recommends reducing protein intake to reduce mTOR activation.

However Dr. Gabrielle Lyon points out in an episode of the Mark Bell podcast how this simplistic logic doesn’t make sense. In a nutshell:

・Sufficient intake of high quality protein is important for maintaining muscle mass.

・Having healthy muscle is well known to be important for longevity in humans.

・The elderly require more high-quality protein because as you age your ability to utilize the protein for muscle growth and maintenance diminishes.

・While protein activates this ‘bad’ mTOR, mTOR is the key trigger for inducing muscle protein synthesis and building your muscle.

・Exercise is well known to be important for longevity in humans, but…

・Exercise stimulates mTOR.

・There is no actual data in real-life humans proving this idea that decreasing mTOR activation through protein restriction extends lifespan.

・If we should reduce mTOR activation to live longer, then we should be sedentary people with low muscle mass. However, we know from actual human data that would decrease your lifespan.

There’s a lot more to this ‘protein decreases longevity’ myth and I think this idea is pervasive enough that I was planning to dedicate an entire post to it.