Andrew Tate's Therapist on digging up our Childhoods (David Sutcliffe) (Patreon)

Downloads

Content

Back in September, I wrote an article titled Therapist argues Andrew Tate is a Hurt Child in response to therapist David Sutcliffe’s interview of Andrew Tate.

<figure> </figure>

</figure>In my article, I broke down a couple sections of Andrew and David’s interview and pointed out that while it made for a very interesting podcast, if this were a standard therapy session, it would be concerning as it seemed like the therapist was encouraging Andrew to view his childhood as problematic.

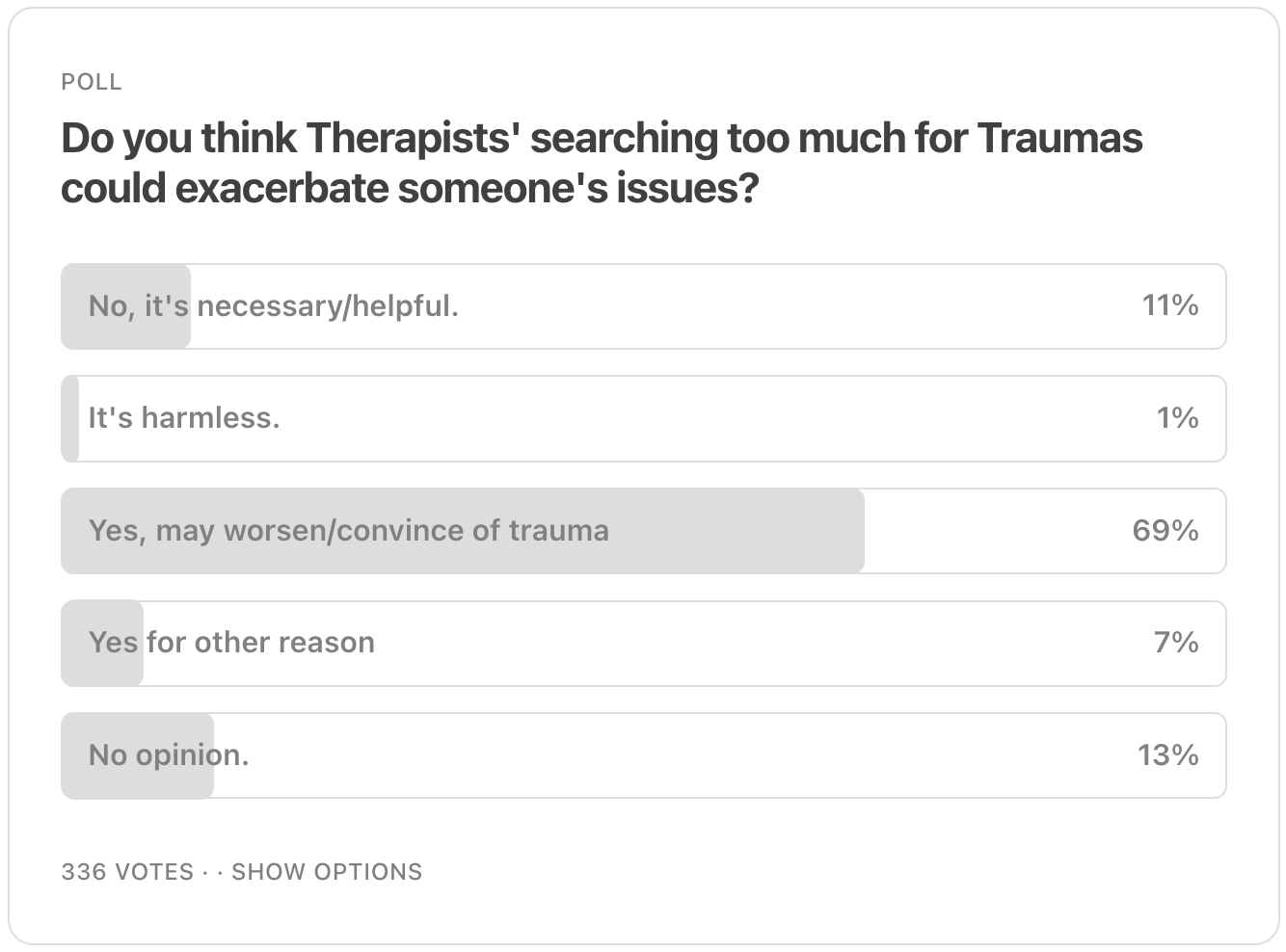

<figure>A poll from that article. </figure>

</figure>David reached out to me and we ended up having a great discussion. Here is a 25 minute clip from the 2 hour discussion. (Scroll down after the paywall for the video. Click the voiceover button above if you’d like to just listen.)

<figure> </figure>

</figure>David Sutcliffe:

If we've been abused by our parents in some way, physically, emotionally, if were betrayed, something happened to us, we have a right to be angry about it. The organism that we are will respond to oppression with rage. That's what it will do. Now, if you're a six year old and your mother or father is screaming at you all the time or hitting you, reacting with rage is going to make it worse. So you're going to suppress that rage, and you're going to develop some other strategy to avoid that behavior or avoid being subject to that behavior.

But that rage is inside you, and it's going to come out somehow, some way, probably in some future relationship, or you're playing sports and all of a sudden you're beating the shit out of somebody, something is going to happen, right? And we all know these parts of ourself where we're in traffic and we just lose our fucking mind. What is that?

I mean, my first time, I went to a week long group therapy retreat, I acted out killing my mother. Now, this sounds crazy, right? But I didn't know that level of rage was inside me. It wasn't a performance. I mean, I was an actor. I know what a fucking performance is. This came out of me. It completely shocked me, the intensity of the feeling that I had. And then it took me right to my pain, right to this place where I felt unseen, unloved by my mother. I then turned that into a story. “I'm unlovable, I'm not enough.”

And I then spent the rest of my life trying to figure out a way to win the love of my mother. So I became an actor and got famous, and that didn't work, and that started me on this journey.

Joseph:

A lot of it makes sense. All that right there. One thing I'm thinking of, though, is how often is therapist, let's say, kind of checking the patient on their interpretation? For example let's say someone says: “I sense I have a lot of hang ups or I feel like I have some sort of trauma because my brother was mean to me when I was a kid.” Would therapist jump straight into, like, “okay, what were the emotions you felt when he was being mean to you? What was the worst thing that he did? Tell me more about that.” Or are they going to, at some point in the process, say, “well, were you annoying kid? Like, was it possible that his meanness was appropriate to your provocation?”

If it was justyour brother saying, like, don't come in my room because you have sticky hands and you're going to get all my stuff dirty… so stay out of my room. But then maybe the kid at the time just interprets that as, “oh, he hates me, and why doesn't anybody like me?” You see what I mean? Are there certain times when the patient could just use some checking and it could be like, well, let's take a look. What did you do? What did he do? Okay, does [interpreting this differently] make you feel a little less oppressed?

David Sutcliffe:

Listen, the whole name of the game is, from my perspective, self responsibility. That's where I'm trying to lead people to. So once this person comes in the room, once I killed my mother, for instance, okay, I get that energy out of me. Now, I know that I've exercised that part of me. I felt my pain. I have an understanding of what happened. I can spend the rest of my life blaming my mother for all my problems, right? And maybe I have a legitimate grievance around that, but at a certain point, it's like, that's what happened. That's what happened to you. There's no right or wrong to it. It just exists. It just is. These are the feelings you had about it. Fair enough. But now you're here, and you've got to accept what happened to you.

You've got to grieve the loss of what you longed for and didn't get. You've got to mourn it. You've got to let it go, and you've got to take responsibility, right? So if I spend the rest of my life being angry at my mother or angry at women because of what happened to me with my mother, that's on me now. I think where it gets sticky is if you don't know, that's why you're angry at women. Like, if you have no connection between those two things, you're kind of in a hell because you just don't know what's going on, and you're stuck in the resentment. And a lot of people who come to me, that's where they are. They're stuck in resentment. They're stuck in blame. It's somebody else's fault. My mom, my dad.

But ultimately, what you're trying to do is essentially, in some way, it's really simple. Everybody needs their feelings validated. I understand why you felt that way. I get it. That makes sense to me that affirmation is so important, especially if they've never gotten that before, because in the absence of their feelings being affirmed, they conclude that there's something wrong with themselves. And so you want to take that off. Now, there may be something wrong with them, but it doesn't mean that there's something wrong with them on a deep level, like, I'm defective, I'm bad, right? There's different that I have quirks that can be annoying, or I was an aggressive kid and I provoked my mother. That's different than I'm fundamentally, at my core, bad and unlovable. And you would be surprised at how many people are walking around with that belief.

I would say most people. It's unconscious, but there's, I think, a place inside many of us that is scared to show all of who we are, because we think that if we show that, we'll be rejected, we won't be loved. Most of us are hiding something. Why are you hiding? What is it you're hiding? You must be something that you feel shame about. Where did that shame come from? Why do you feel ashamed about that? What is the story you tell yourself about that shame? That's the matrix that I'm trying to help people unpack.

Joseph:

I see one thing on the affirming feelings is I would kind of think that there are some feelings or some conclusions that someone might make at an early stage in their development that don't make any sense, that are actually pathological or they are not, let's say an appropriate feeling in the sense that it is not a feeling that helps them. So just to give you an example, I was looking at this video between he's like some certain certification. I don't know if it's a psychotherapist or clinical physician or a physician or whatever it is, but he was talking with someone in his community who was having issues, and it's one of these things where you have a live session, and then they can talk and explore the situation.

Anyways, the guy clearly had a very difficult childhood, and his mother was incredibly overbearing berating him for, like, hours a day. And then the minimum, the average, was an hour a day. He was being berated for how useless he is. And he even kept a diary of this, like a journal. Like, okay, today was an hour, yesterday was 45 minutes. So he had a pretty rough situation. And let's say therapist, therapist said, asked him about that asked him about how he felt about that. They started getting talking about suicide, and then he said things like, therapist said something like, I'm surprised you're still here. As in, I'm surprised you didn't commit suicide.

And so I could tell that was a type of empathy and a type of I see how you arrived at that thought process, but I was thinking, is that really helpful to say? Like, the logical conclusion from this sequence of events is that you should kill yourself? I know this is an extreme example.

David Sutcliffe:

But no, it's a good example. Well, what you're affirming, yes, it makes no sense, but it made sense to the child. And so you're affirming that logic pattern because otherwise they feel insane. It needs to be seen. They need to be acknowledged. They need to be known in that way. And what it does is it relaxes them. Here's the thing. We all long to be seen. We want to be understood. We want to be known. And what happens very often with children and certainly happen with me, things are happening in your environment. You can't make sense of them, and you're alone with all of those feelings. You're four years old. You're six years old. You're eight years old, trying to figure out what the hell is going on. All children are essentially narcissists, so they make it about themselves.

They don't have the discernment to say, oh, mom has issues, and I'm not going to take this personally. They can't not take it personally. So what you're trying to do is affirm the feeling without agreeing with the story, right? So somebody will come in and they'll say, this happens all the time, right? They're talking about their husband and their wife and how horrible they are. And you're listening, and you're like, yeah, maybe she's horrible, but maybe you're also contributing to this. Right? But you can't lead with that. You have to let them discharge their frustration, and you have to develop connection and safety with them. And the way to do that is to say, I understand. I can understand why you'd feel that way. I'm not agreeing with the story. I'm not saying, you know, it sounds like your wife's a fucking bitch.

I'm saying I can understand why you'd feel that way. That must have been painful. I can imagine you were scared. Whatever it is, you're just affirming the feeling without agreeing with their interpretation of the story. And once that trust and safety is developed, they call it unconditional positive, regard it's from that place that you can then lead them into a deeper level of awareness and say, well, how are you contributing to this? Are you seeing this clearly? Maybe there's something from your history that's being projected onto this situation, because when you told me about your wife doing this thing, I didn't see it the same way that you described it. So I wonder if there's some distortion that you have, and maybe we could explore that it's things like that. But at the beginning, we just need our feelings affirmed.

I mean, that's what I want when I'm upset about something. I just want to fucking rant for five or ten minutes and just have a person, yeah, fucking, yeah, guy's an asshole. Totally. I'm like, fuck you. And then I calm down. I'm like, all right. Fuck. Okay. And I bring it back to myself, and I know what I'm doing. Right. But the client, they don't know yet. So you're trying to lead them there.

Joseph:

So what it kind of sounds like is part of the affirming, the feeling process is it gets you on their side. Absolutely. Let their defense down. And so that's kind of a stepping stone where you're like, okay, I see how the story you had arrived at that feeling. But, okay, now that we agree on that, is there a possibility that the story is wrong?

David Sutcliffe:

The story is always wrong. Your story is wrong. Your mind is a horrible narrator of your own experience. That's the place to start. I mean, that's how I am when I'm in a fight with my lady. I don't know what's going on. If I'm triggered, it's 100% sure that I don't even know what I said. I don't know what she said. I think I know, but if I'm in my defense, I know that I'm not reliable. The only thing I know is how I feel. I'm angry, I'm hurt, I'm upset. That's it. Everything else is pretty much nonsense. And that's also what I'm trying to teach people. It's like, just come back to the feeling. That's all you can be certain of.

Because we're interpreting the story through the lens of our history, and we're very attached to our stories because our stories are belief systems. We have a narrative that's running in our mind all the time, and really, on some level, I think therapy and all spiritual work, whether it's meditation or whatever, it's about exactly that it's getting out of the story, getting out of being attached to a particular kind of narrative. I mean, I think we're going through something in the culture right now where the stories that we've been telling ourselves for the last 50 years, people are seeing, this was all fucking bullshit. What the fuck is going on? And that's why there's a collective freak out. It's just what happens with a client.

It's like when they start to realize that the story they've been telling themselves is wrong, well, they have nothing to hold on to. They don't know what's real anymore. So it's very scary to let go of. Even if that thing they're holding on to is causing them suffering, it's all they know, right? So convincing them to let go of it is not an easy thing, but usually life will force it on you in some way if you keep wanting to grow and evolve. Life is going to show you where your limitations are. Life is going to show you where your map of reality is not accurate. And you're going to keep bumping up against it over and over again until you learn the lesson. And that it's all about you. That reality is essentially a projection. It's not out there, it's in here.

And then you project it out. So your reality, as Tate said perfectly, it's just a mirror for your inner world. And once people understand that, then they come back to self responsibility. And ultimately, what happened with your mother and your father ultimately is irrelevant. But if you're attached unconsciously to the story of it's not irrelevant at all. It's everything. And until you understand that and liberate yourself from that, you're a slave to those feelings. You're acting unconsciously. You're not truly free. Now, can you actually get free? The Matrix movie, I think the conclusion was, you get out of one Matrix, you're in another. It's continual matrixes forever. And so all you can do is just accept, okay, this is what it is, love and accept, which is the message of Christ, right? Like, love, war, peace, tenderness, mayhem, violent.

I just have to learn to be with it. All that ultimately, is the highest level of consciousness. And so can we give that to ourselves? Can we accept ourselves in our own beauty, but also our own ugliness? Can we accept the madness that lives inside us and see the goodness of it? Because there's really no way, really out of it. And in fact, there's great gifts in it.

Joseph:

Depending on the way in which therapist questions the patient or leads them to investigate their childhood. Could it be done in a way such that the question turns into kind of a suggestion? Like, if you're asking, were there any things your parents did that hurt you? Then that could have them say, oh, I never thought about it like that. Let me search for ways that my parents hurt me. I'm wondering if there's two. And if you're saying, what are the ways your parents hurt you? But then you're also saying, what are the things you're grateful for that your parents did, then there's a kind of balance. My kind of worry is it too often the case that it's, let's look for any transgressions and let's work from there?

So then the person's interpretation of their past is kind of unbalanced to be, let's say, ungrateful for or resentful for more than the reality would suggest is warranted.

David Sutcliffe:

Yeah, well, I think that can be a trick of the mind to continue to come back to that. I hear exactly what you're saying. I think the blind spot is that you're projecting your own stuff onto your clients. That's really the danger, because none of us are perfectly conscious. That's why most therapists do. And if they don't, they should get supervision. So you're trying to make sure that you're as clean as you can possibly be. And that is a problem. Right. And I saw it in the interview with Tate. I mean, when I watched it, I was like, I'm projecting. It's fine, because I let it all go. If I make a suggestion and he doesn't bite, I don't necessarily push unless I feel that there's an opening.

And the way that I knew that I had created safety with him is that he stayed with me through it. Right. He was present in his way through all of it, and there kept being invitations.

Joseph:

Yeah. It never looked like you made him uncomfortable.

David Sutcliffe:

Exactly. Because you have to stay in connection. Right. Like, you have to stay in some way in favor and be garnering their trust, but also challenging, especially for a guy like Tate. He wants to feel challenged. Right. That's exciting to him. Listen, people come into my office all the time and say I said, well, tell me about your childhood. They're like, My childhood was great. No problem. And I'm like, okay. I don't really I'm like, okay. And then I'm what's going on? Well, this and that, and DA DA. And they'll tell me their whole story, and then eventually I'll ask them what happened with growing up, and they'll tell me a story, and I'll be like, what?

I said, wow, that sounds like kind of traumatic to me, because something that they just lived with it, they dealt with it, they moved on. And it makes sense that they don't want to make it tragic because it was so painful. They want to disassociate from it now. I'm not trying to I mean, maybe I am. I'm sure I am, actually. Like, making hypnotic suggestions is sort of what you're suggesting, but hopefully I'm doing in a way that's leading to some kind of truth. They're very vulnerable, and you have a lot of power over them, and you have to take that with a lot of responsibility. And I guess the skill is attunement. And sometimes you can just feel when somebody's, like, not in the truth, it's a vibe.

It's like you both know that they're lying not lying, but that they're in some kind of distortion, and you just want to meet them there. And I think the thing is, you just hold it lightly, and you really be soft and tender. But I think you're right. It's a good question to ask, because I think it's really tricky. And it's very important that therapists do not oppose or impose an agenda onto their clients, whether it's just to feel useful, because I want to be a good therapist and I want to keep this client, and I want them to like me, and I want them to think that I know what I'm doing. Or we're projecting, as I said earlier, our own unconscious material onto them.

So I had issues with my father, and now I'm sitting across from this person and I'm hearing stories about what happened with their father and I'm relating to it. And then I'm making suggestions about what it may be, but it in fact is related to my own stuff. And that's something that you have to be incredibly mindful about. And I don't think anybody gets it right 100% of the time. It's a tricky thing to navigate.

Joseph:

I would imagine most people are not going to therapy thinking that therapist is going to be like this perfect, almost like AI avatar that only says the most unbiased, optimally designed questions going in and out.

David Sutcliffe:

I hope not. I mean, I try to demonstrate my humanity, I was going to say as often as I can, but in appropriate moments so that they're aware that I'm a human being. I have my stuff. I don't have it all figured out. I'm just going to try to be a mirror for you. What I'm modeling more is the acceptance of my own humanity. So I'm imperfect, but I continue to do my best to love myself. Despite that. I try to liberate myself from shame, from being too hard on myself. I'm not perfect at it, but here I am, this imperfect person doing my best. And that's all we can do. And so I want to model that behavior for you.

The tricky thing, and this is kind of inside baseball, but it's really interesting is that I talked about what we call countertransference, like your stuff that you might put on your client. But what's also happening is they're putting stuff on you so they're not seeing you. They're seeing their father unconsciously, their lover brother. I mean, in my case, I'm a man. So it's these things, authority. So all of their issues with all of those people in their life are all at some point going to be projected onto you. And so you have to be aware of and hold that projection. You're not in real relationship, you're in relationship, but there's a dynamic that's being created. And so for me, I know that the archetype that I represent for people is the good dad. Whether they're aware of it or not. I'm the good dad.

I'm the nice guy. I understand, I get it. I work out, I'm kind of cool. So you know what I mean? I'm accessible. But at the end of the day, I'm the good dad. And sometimes I'm really loving and caring and gentle and understanding. And other times I'm like firm and direct and get your shit together and I see through your bullshit. Let's go. That's the avatar that I work with because I got the gray beard. I'm 54. That's what's happening. So you're always using that. If you use it wisely, you can help people. Because people wanted a good dad.