You should probably eat more protein (Patreon)

Downloads

Content

What’s wrong with the food in this picture?

<figure>The Revis family of North Carolina. Food expenditure for one week: $341.98. </figure>

</figure>This is one family from America’s weekly groceries per Time Magazine’s 2013 article Hungry Planet: What the World Eats. The family actually looks pretty trim and healthy, but if someone were to critique their groceries, they might say it’s too much processed carbs, others would say it’s too much sugar and salt, others would say it’s too much fat and some might say there’s too many animal products.

Next, consider this:

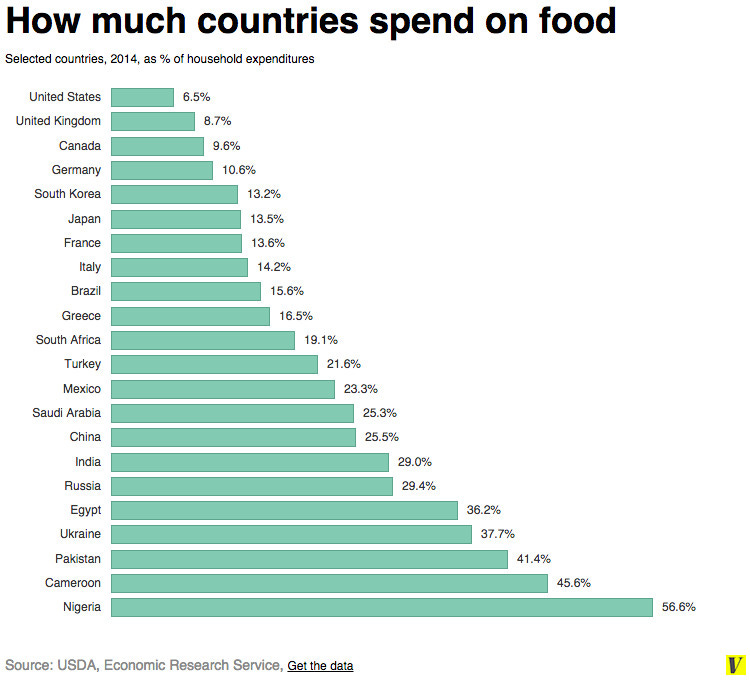

<figure>(USDA/Vox) </figure>

</figure>Reporting on USDA data, Vox claims that “Americans devote just 11 percent of their household spending to food, a smaller share than nearly every other country spends on food consumed at home alone.” Now part of this is because America is a wealthy nation so people don’t have to spend much on food, but considering America spends a lot less than France or Norway, part of it is likely due to the fact that Americans simply buy cheaper food.

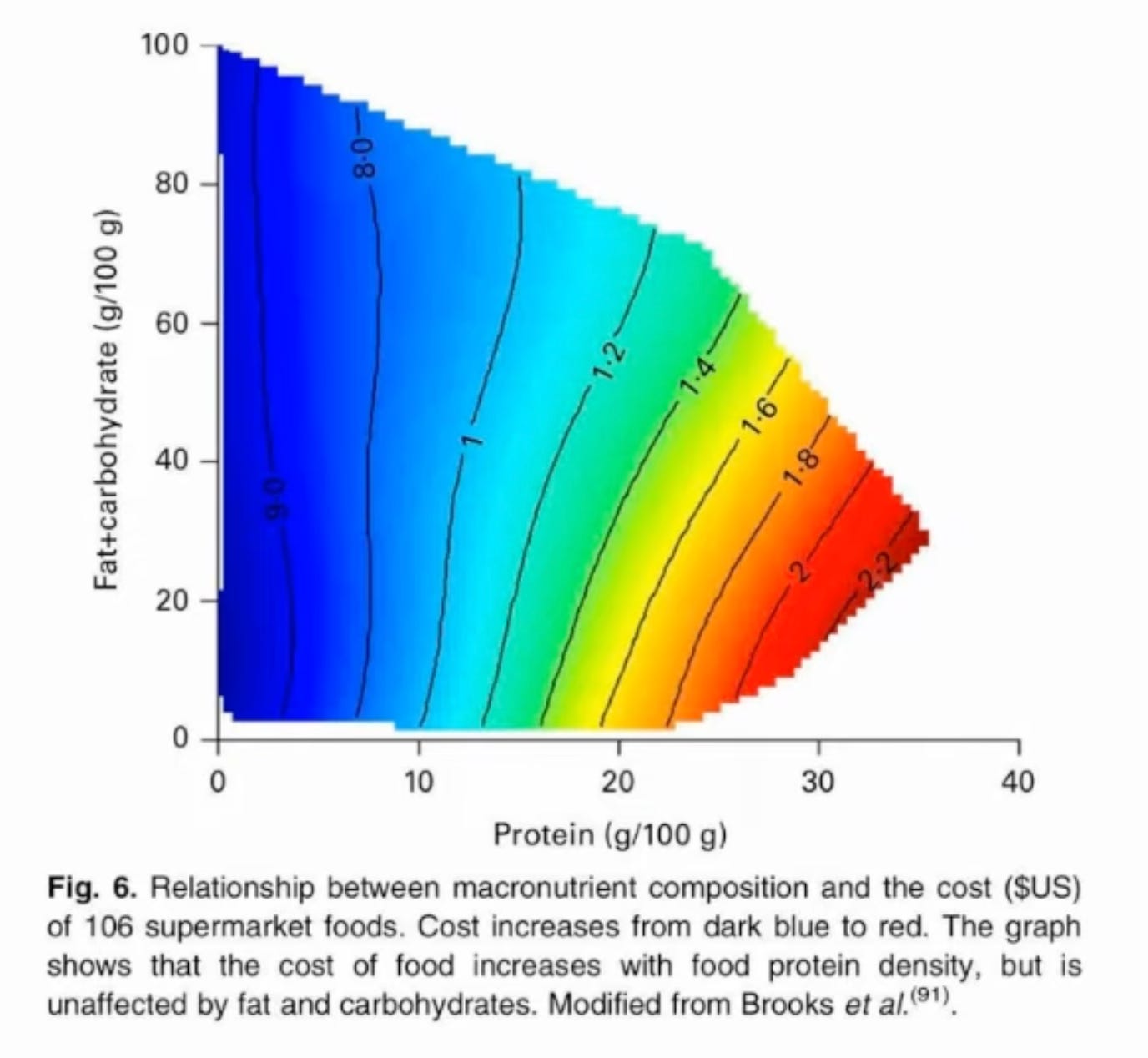

I don’t think you’d be surprised to hear that cheaper food makes you fat. It’s true that cheap processed food is loaded with processed carbohydrates and seed oils, but what it doesn’t have much of is protein. Protein is the most expensive macronutrient.

<figure> </figure>

</figure>This study found that foods high in fat and/or carbohydrate were cheaper, and the more protein a food had, the more expensive it was.

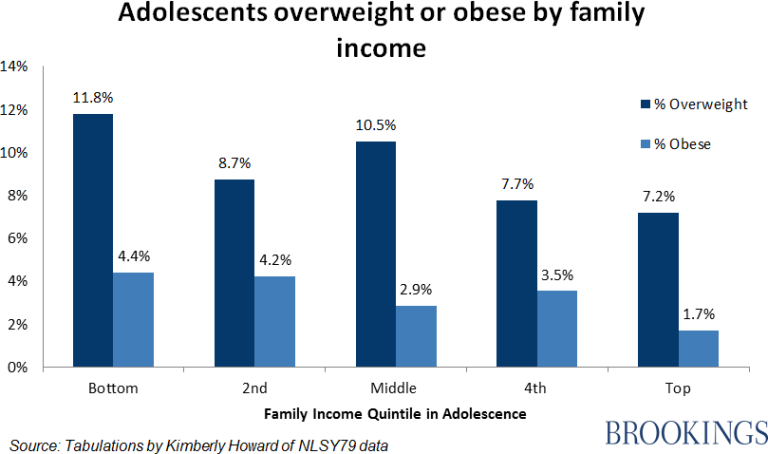

<figure> </figure>

</figure>NLSY79 data suggests that as income goes down, obesity goes up.

So of course cheap foods have all kinds of negative attributes, but could protein have anything to do with obesity?

<figure> </figure>

</figure>Here’s the spoiler alert courtesy of Dr. Ted Naiman :

“Every single human obesity study you will ever look at, ever, at all, period, in the history of medical literature - the more protein people ate, the better. Always. Completely. Like, there's no exception."

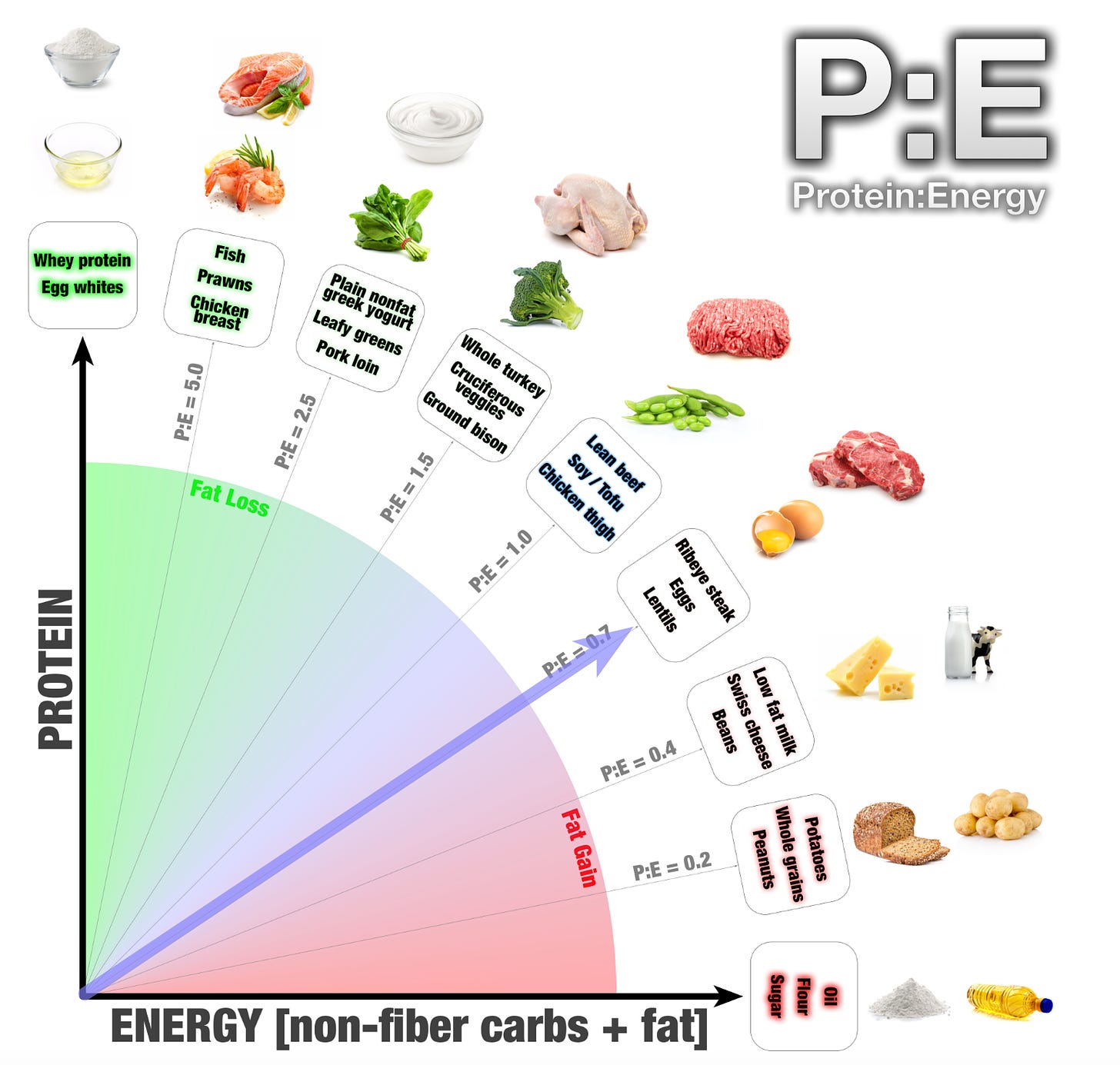

Ted Naiman’s philosophy on maintaining a healthy weight is really simple. You need to improve your protein to energy ratio. Try and look at the macronutrients like this: We need protein to build our muscles, maintain our cellular machinery and so on: it builds us up and maintains our biological machinery. Fat and carbs we’ll consider as just an energy source. So you want to get plenty of grams of protein per calories of fat and carbs. Protein : energy. For example, a ribeye steak has plenty of protein and plenty of fat but no carbs, so its P:E ratio is 0.7. Lean beef has no carbs and even less fat, so its P:E ratio is 1.0 . Then of course things with tons of calories relative to protein are going to have really low P:E ratios - potatoes and peanuts have a P:E of 0.2 .

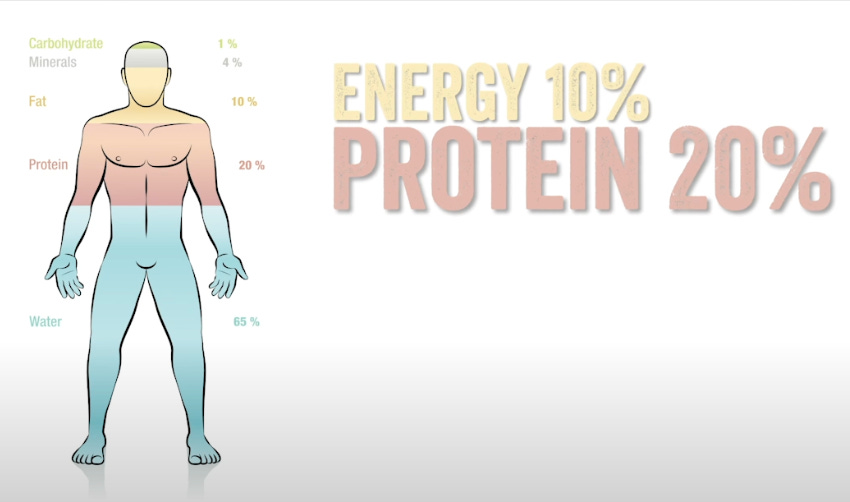

<figure> </figure>

</figure>An interesting way to think about it is that the body of a lean, healthy person would have a pretty high protein to energy ratio. They would have plenty of skeletal muscle, not so much fat on their body. The more overweight and unhealthy you become, the lower your protein to energy ratio will become.

<figure> </figure>

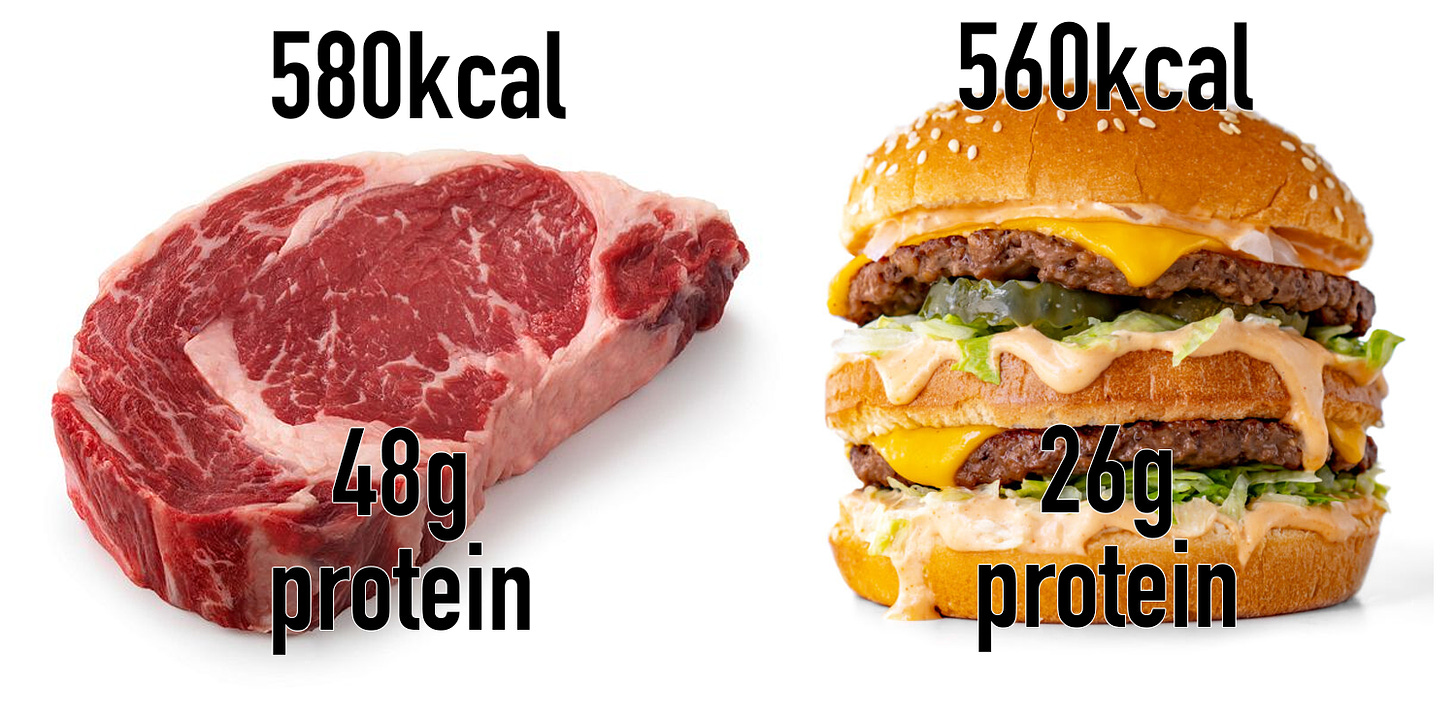

</figure>Ted Naiman has done a lot to popularize the “Protein leverage hypothesis” which essentially suggests that humans (but not only humans) prioritize protein to where if they are given a low in protein, they will overeat in order to get more protein. A high-protein diet will hit their protein needs quicker so the satiety signal comes quicker with less calories. So for example you may be full after a 200g ribeye steak but might still want a little something after eating a Big Mac even though they both provide around 570 calories because the ribeye steak is giving you 48 grams of protein but the Big Mac only gives you 26 grams of protein.

<figure> </figure>

</figure>"You can take any human or any omnivore mammal and feed it a diet high in fat, high in carbs and high in energy density and it will automatically overeat by about 30% of calories and become obese." -Ted Naiman

One randomized controlled trial from 2011 wanted to test this hypothesis and they indeed found that:

Lowering the percent protein of the diet from 15% to 10% resulted in higher total energy intake.

Interestingly, the higher calorie intake in response to the low protein diet came “predominantly from savoury-flavoured foods.” Apparently if you don’t get enough protein, you’ll crave things that taste like they should have protein in them.

The study concluded:

In our study population a change in the nutritional environment that dilutes dietary protein with carbohydrate and fat promotes overconsumption, enhancing the risk for potential weight gain.

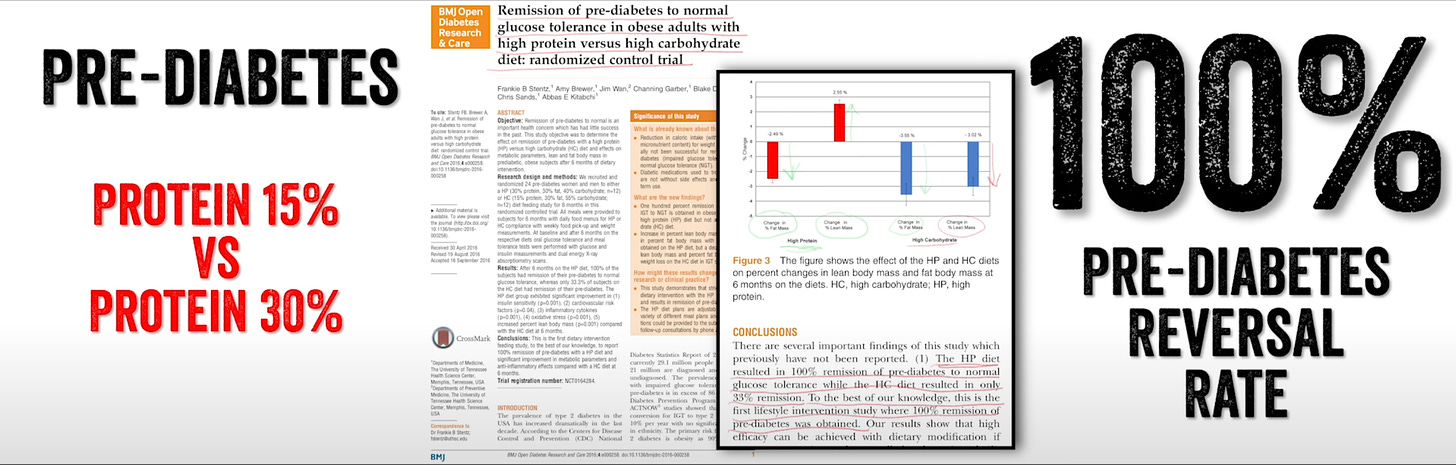

Backing up his claim that “every study” always shows more protein is better for metabolic health, Ted Naiman presented slew of studies including one comparing 15% protein diet vs. a 30% protein diet in people with pre-diabetes. The high protein group not only lost more weight but they had a 100% pre-diabetes reversal rate.

"The study authors said to the best of their knowledge, nobody had ever gotten a 100% prediabetes reversal rate ever, doing anything."<figure>

</figure>

</figure>A study from just this year found that on average, each 1% increase in protein lowers total calorie intake by about 1%. A 2022 study found more total protein was associated with less incidence of metabolic syndrome. Another 2019 study found that higher total protein intake was associated with a reduced risk for diabetes and pre-diabetes.

The thing I like about focusing on protein is it really simplifies your diet. Alex Hormozi says his diet rule for the past 20 years is to simply eat 200 grams of protein and then eat whatever he wants after that.

<figure> </figure>

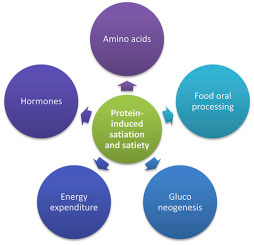

</figure>How does protein blunt your appetite?

Most of this protein magic is coming from the fact that protein simply quenches your hunger much more than carbs or fat. Per Revisiting the role of protein-induced satiation and satiety :

“Many studies have investigated the effects of protein on satiety and satiation, and most but not all have found that, at sufficiently high levels, protein has a stronger effect than equivalent quantities of energy from either carbohydrate or fat”

So what is so special about protein? Well, a couple things are going on.

<figure> </figure>

</figure>1. Diet Induced Thermogenesis - Is it the meat sweats?

<figure> </figure>

</figure>The meat sweats are thought to be the consequences of diet induced thermogenesis (DIT). When you eat food, it takes a little bit of energy to break it down and protein takes the most energy to break down. This increased energy expenditure is one idea behind the meat sweats phenomenon (though one theory is that’s just due to the fact that we often use capsaicin containing spices to season meat.) In any case, the earlier paper says that protein’s high DIT is a component of its satiating effect.

Energy expenditure is not clearly dependent on the protein source, although there is some evidence that animal proteins produce higher energy expenditure than vegetable proteins, resulting in reduced appetite

2. Protein Increases ‘satiety’ hormones

This one’s pretty straightforward.

Protein-induced satiety coincides with a relatively high increase in concentrations of anorexigenic hormones or a larger decrease in orexigenic hormones.

When people are satiated by protein, there’s more satiety-inducing hormones and less hunger-inducing hormones floating around in the body.

<figure> </figure>

</figure>Just one example is a study that found that an amino acid mix given to obese adolescents reduced their appetite. This appeared to be due to an increase in the appetite suppressing peptide GLP-1, probably in response to the intestines sensing the presence of certain amino acids.

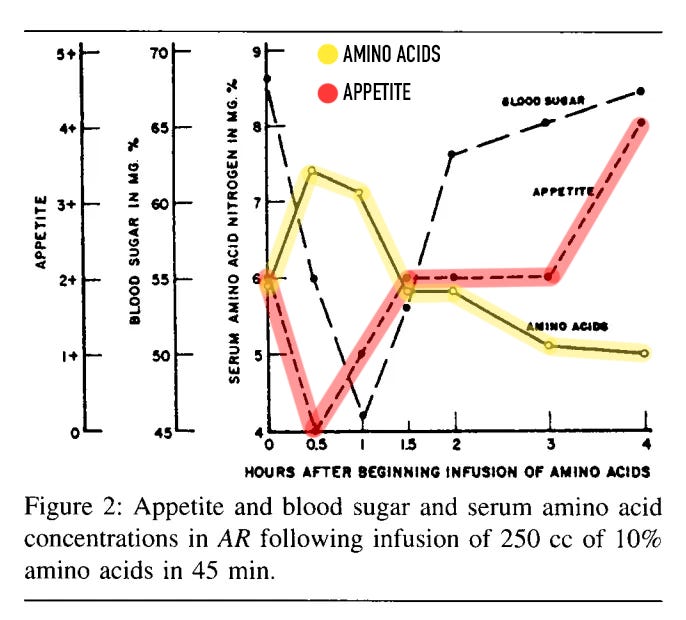

3. Aminostatic hypothesis - Body maintains amino acid balance through hunger

<figure> </figure>

</figure>This is a really cool graph from Relationship Between Serum Amino Acid Concentration and Fluctuations in Appetite . Take a look at the red line (appetite) and the yellow line (serum amino acid concentrations). They’re pretty tightly linked to where amino acids go up, appetite goes down, amino acids go down, appetite goes up. As the study puts it:

Whether induced by feeding of protein or of amino acids, or by infusing amino acid mixtures, a rise in the serum amino acid concentration appears to be accompanied by a waning of appetite. The subsequent increase of appetite is accompanied by a fall in the amino acid concentration.

There’s something called the aminostatic theory that basically says the body is always trying to maintain a certain level of amino acids. When it senses there is not ‘enough’ amino acids present, it will make you hungry. According to The Role of Psychobiological and Neuroendocrine Mechanisms in Appetite Regulation and Obesity

The aminostatic theory proposes that amino acids in the blood have a significant role in defining satiety. …According to the aminostatic hypothesis, amino acids act as peripheral signals to the brain in order to maintain the long-term balance between energy intake and energy expenditure as well as body fat mass over days or weeks.

Put another way, food intake is adjusted in response to amino acid availability to meet the protein demands of the body.

<figure> </figure>

</figure>4. Protein raises ketones?

Hard to say how significant of a factor this is, but another really interesting way protein may reduce appetite is by producing ketones. High protein diets rich in ketogenic amino acids may result in increased plasma ketone body concentrations, which in turn contribute to increased satiety. Ketones are known to be an appetite suppressant.

The ketogenic amino acids are Leucine, Lysine, Phenylalanine, Isoleucine, Threonine, Tryptophan, Tyrosine.

According to A high-protein diet for reducing body fat: mechanisms and possible caveats :

Instead, the authors observed an increased production of ketone bodies (especially beta-hydroxybutyrate) in response to the high-protein diet. The increased concentration of beta-hydroxybutyrate may act as an appetite suppressing substrate.<figure>

</figure>

</figure>Too little protein is definitely a thing. Is there even a “too much” protein?

The RDA for protein is set at 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight. So, if you’re a 70kg man, you should be able to get 56 grams of protein and call it a day. Two big macs and a handful of almonds should do the trick. However, what some don’t realize is that the RDA is the minimum required intake to prevent deficiencies, it’s not what’s optimal.

In fact, double the RDA of 0.8g/kg is likely where you want to be. Recent research has found 1.2kg to 1.6kg of protein is better for health.

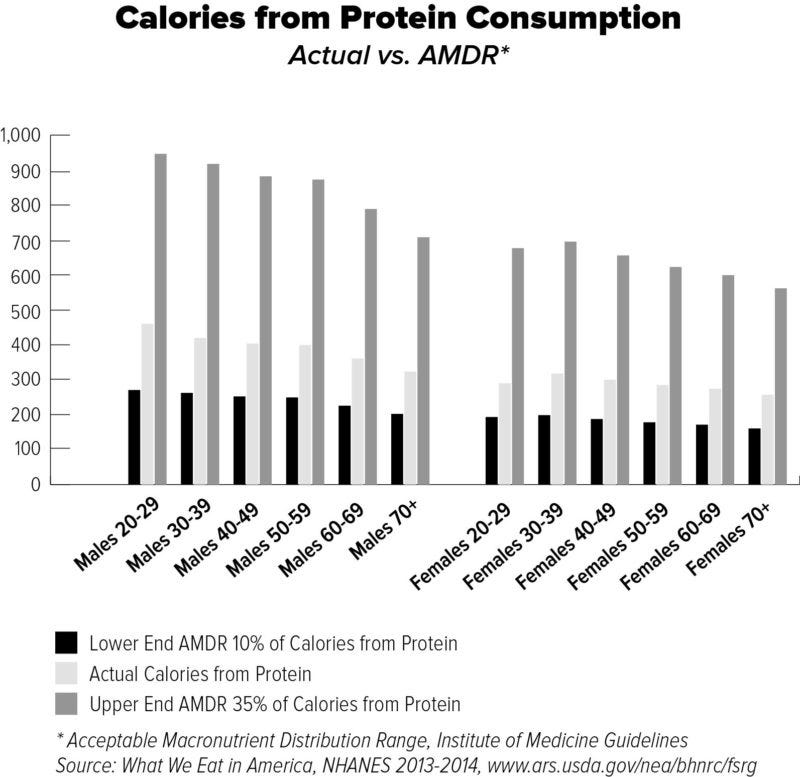

<figure> </figure>

</figure>There’s something called the “Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range” which is set based on epidemiological evidences that suggest consumption within these ranges plays a role in reducing risk of chronic diseases. (S) As you can see in the chart above, while the average American is at least above the lower end of the AMDR, they are far from the upper end. So, could we stand to get more protein?

Well, first let’s establish that an amount of protein that is “too much” has not been established.

<figure>Dr. Gabrielle Lyon </figure>

</figure>Dr. Gabrielle Lyon states that we haven’t seen negative effects from upper limits of protein - 3.3g per kilogram, which is 4 times the RDA. One study having women eating over four times the RDA as much as 3.4g/kg per day did not have any deleterious effects. The U.S. and Canadian Dietary Reference Intake review concluded that there was not sufficient evidence by 2005 to establish a an upper limit for how much protein can be safely consumed.

<figure> </figure>

</figure>One study did suggest the combination of super high-protein (35% of calories as protein) and low-carb reduced total testosterone. If you’re eating 2500 calories, 35% of that as protein would mean about 220 grams of protein. Let me remind you that’s a lot. Even Arnold Schwarzenneger back in the day allegedly ate around 4500 calories and 250 grams of protein, meaning only 22% of his calories came from protein. Even then, it’s hard to tell if the drop in testosterone in the people in that study was due to the protein, the low-carb aspect or a combination of both. Paul Saladino admitted that reintroducing fruit and carbohydrates into his long-term ketogenic carnivore diet significantly increased his free testosterone due to lowering his SHBG.

But at the end of the day, to get ‘too much’ protein, you’re going to have to try pretty damn hard.

“In 20 years of medical practice, I have never once looked at a patient and said ‘you’re eating too much protein.’” -Ted Naiman

Maybe you’ve heard of this idea that protein is bad for the kidneys and liver?

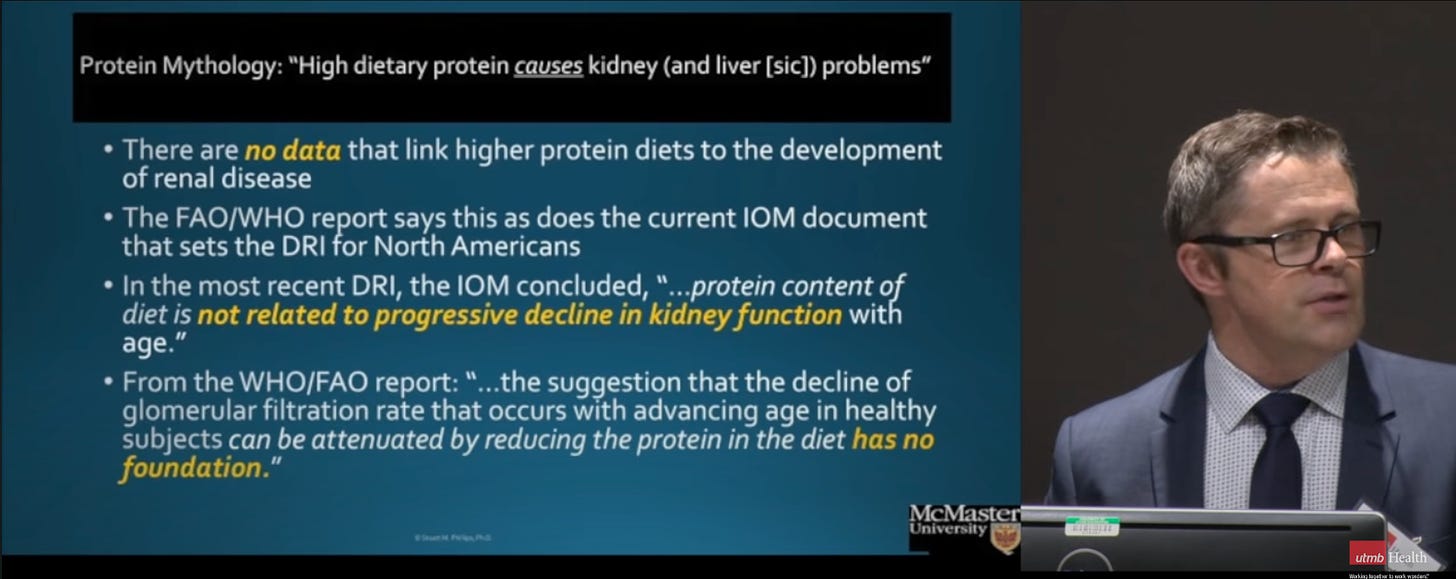

Dr. Stuart Phillips, a professor and Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Skeletal Muscle Health talked about that in a lecture at UTMB Health that “There’s no data. There’s no data that link the two. None. Not a scrap.”

<figure> </figure>

</figure>He explains that the the idea that protein is bad for the kidneys came from the fact that people who already have renal disease do better on lower protein diets. Though, it’s the disease that made the kidneys unable to properly handle protein, not the other way around. I’d make the analogy that it’s like saying people with prostate cancer have trouble peeing so water causes prostate cancer.

<figure> </figure>

</figure>Why would we need any more protein than the minimum?

Protein is much more than just the brick and mortar used to build muscle. Of course our bodies don’t require “protein,” but the amino acids that protein is composed of.

The review article Amino acids: metabolism, functions, and nutrition lays out that Amino Acids (AA):

・Act as cell signaling molecules

・Regulate of gene expression.

・Act key precursors for syntheses of hormones and very important biological substances like dopamine, serotonin, epinephrine, norepinephrine, and thyroid hormones just to name a few

・Some AAs (called functional amino acids) regulate metabolic processes necessary for maintenance, growth, reproduction, and immunity.

Dietary supplementation with one or a mixture of these AA may be beneficial for

(1) ameliorating health problems at various stages of the life cycle (e.g., fetal growth restriction, neonatal morbidity and mortality, weaning-associated intestinal dysfunction and wasting syndrome, obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, the metabolic syndrome, and infertility);

(2) optimizing efficiency of metabolic transformations to enhance muscle growth, milk production, egg and meat quality and athletic performance, while preventing excess fat deposition and reducing adiposity. Thus, AA have important functions in both nutrition and health.

If your eyes glazed over reading that, just know that amino acids are important enough that there’s an entire academic journal (titled Amino Acids) dedicated to them.

That’s cool and all, but do we need more protein than we already eat? Is eating another steak going to make our cells signal … faster? Does eating 10% more protein each day mean we have 10% more dopamine?

While I think keeping people satiated on less calories is already a huge win, in another post I’ll talk more about the other roles of protein in maintaining health and why Dr. Gabrielle Lyon and Dr. Don Layman recommend a “muscle centric” approach to health.