AI Crisis: The danger of AI working perfectly (Patreon)

Content

*Note: None of this article was written by ChatGPT

<figure>This image was generated entirely from a single text prompt to a generative AI called Midjourney. </figure>

</figure>The first website was published in 1991 - not long after I was born. I was in High School when social media finally came on the scene. MySpace was competing with Facebook at the time but I spent most of my time on AOL Instant Messenger. Considering how easy it was for me to lose a couple hours of sleep to sitting in an uncomfortable chair waiting for a reply to my AOL message on the family desktop computer, I’m truly glad I didn’t grow up with a smart phone. The iPhone came out in 2007 before I graduated High School but at the time I didn’t see the appeal.

Barely the next year in 2008, author Nicholas Carr wrote an article titled Is Google Making us Stupid?

The advantages of having immediate access to such an incredibly rich store of information are many… But [it] comes at a price. As the media theorist Marshall McLuhan pointed out in the 1960s, media are not just passive channels of information. They supply the stuff of thought, but they also shape the process of thought. And what the Net seems to be doing is chipping away my capacity for concentration and contemplation. My mind now expects to take in information the way the Net distributes it: in a swiftly moving stream of particles. Once I was a scuba diver in the sea of words. Now I zip along the surface like a guy on a Jet Ski.

The content of that Nicholas Carr article is surely not news to you. It’s more or less common knowledge that the internet can make us impatient, inattentive, anxious and more socially awkward. Ironically the internet has diminished our relationships, but you pretty much have to use the internet to effectively participate in society.

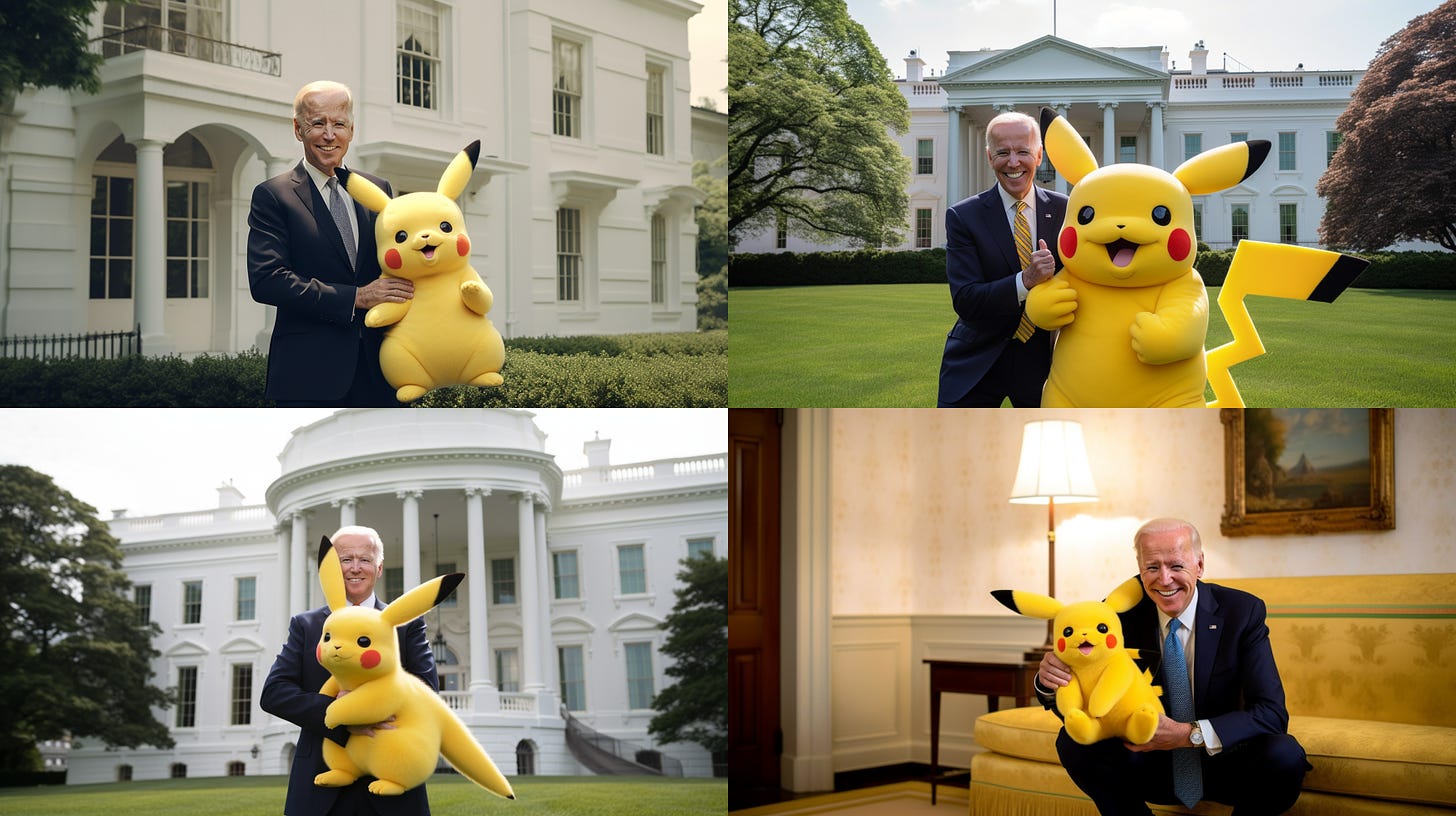

In case you are unaware of how good AI is getting, here is what the text-to-image AI Midjourney generates when I give it the prompt “a realistic photograph of Joe Biden with Pikachu at the White House.”

<figure> </figure>

</figure>The AI discussion is a spectrum ranging from AI is going to destroy the world to AI will bring in the Utopia. The typical idea for how AI will take over the world is a kind of careful what you wish for situation. You give the AI a goal, and because it does not have human values it may achieve that goal in a very undesirable way no one could have expected.

<figure> </figure>

</figure>AI Turbocharged Phone Scam

For example, you give the AI a goal like ‘make 1 million dollars as fast as possible and deposit it into Silicon Valley bank account with account number 1234567.’ You may expect it to run a successful business but what would be faster would be to use an AI with similar capabilities to ChatGPT to generate an innocent script simply designed to keep a person on the phone as long as possible, but a few seconds should enough.

Hello, is this so-and-so? … Sorry, is this the so-and-so with number 555-555-5555? … OK Great. Is now a good time to talk? … Well, I think you know what this is about … No it’s nothing serious, I just wanted to talk regarding …

The AI will then use a text-to-voice service like ElevenLabs to turn that script into a realistic sounding voice and use various services like rocketreach.co or Apollo.io to generate a list of names with corresponding telephone numbers. It would then use twilio.com to make calls to these people with the earlier generated script. The person answering the phone can be totally dismissive, with responses like:

‘Yes. Yes. What’s this about? I don’t know, that’s why I’m asking. OK I’m not interested, bye,’

because the AI is only calling them so it can record their voice.

The AI will save a recording of that person and then plug that recording into ElevenLabs to clone that person’s voice. Now, it can generate a number of scripts like one that fishes for personal information or one that asks for a ransom. With these scripts it can call a member of that person’s family. Something like ‘Hey Mom, I’m at the DMV and it’s already my turn can you remind me my Social Security Number real quick?!?’ would be read out in that person’s daughter or son’s voice. The ransom tactic would probably use two voices:

AI Voice 1: Ms. so-and-so? We have your daughter.Cloned Daughter’s Voice: Mom I’m so scared, they just took me!

AI Voice 1: If you ever want to see your daughter, send $10,000 to the following Bitcoin address.

@bethroyceI feel the need to tell everyone I know about this. Literally the scarriest moment of my entire life #scam #scammers #scammed #hostagesituation #trauma #phonescam #fyp #foryoupage #fypシ #viral

Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

It would be possible for the AI to even make it look like the call was actually coming from that family member.

Remember that the AI will be able to track what happens in each scenario to improve its tactics. It may try various scripts for the initial step where it is just trying to get people talking enough to clone their voice until it arrives at a script that consistently gets a full minute of the person speaking. Similarly, it could then come up with more effective phishing and ransom scripts.

If this sounds farfetched, some of it has already happened.

Just in April of this year, an article titled AI clones teen girl’s voice in $1M kidnapping scam: ‘I’ve got your daughter’ was published. It explains how a woman received a call from an anonymous number that started with an AI clone of her daughter’s voice saying “Mom, I messed up!” Next, a man told her that he had kidnapped her daughter and demanded $1 million in ransom.

“I never doubted for one second it was her,” distraught mother Jennifer DeStefano told WKYT while recalling the bone-chilling incident. “That’s the freaky part that really got me to my core.” (S)“After a chaotic, rapid-fire series of events that included a $1 million ransom demand, a 911 call and a frantic effort to reach Brianna, the “kidnapping” was exposed as a scam. A puzzled Brianna called to tell her mother that she didn’t know what the fuss was about and that everything was fine.” (S)<figure>

</figure>

</figure>This imaginary phone scam is nice and scary and we can imagine up all kinds of ‘careful what you wish for’ type sci-fi movie plots like …

A doctor with a computer science degree creates a generalized AI that, with the right resources, can complete any task. He gives the computer the task “make sure no human has cancer.” Now Vin Diesel and the Rock have to ride expensive cars to save the world from a mindless AI attempting to eradicate human cancers by simply eradicating all humans.

However, maybe we should also be wary of AI working exactly how we want it to.

<figure> </figure>

</figure>The problems with AI working how we want it to

In Peter D. Hershock’s 1999 book Reinventing the Wheel, A Buddhist Response to the Information Age, he discusses Ivan Illich’s observations on the “counter-productivity” of progress.

In a study of transportation technologies and travel time, he discovered an apparent paradox: the faster we travel on the average, the more time we spend traveling. More precisely, the breakoff point is at 19 mph—roughly the speed of a brisk bike ride. As technologies are developed that allow the average vehicular speed in a society to rise above this point, increasing amounts of time will be spent per person, per day just getting around. Because we can go faster, we go more—so much more that we find ourselves spending 300 to 500 percent more time transporting ourselves than people who are limited to horse-drawn carts and bicycles.

Hershock spends a good chunk of the book discussing how technologies are not just tools. They are more like a symbiote that doesn’t just allow us to do the same behavior quicker, they change our behavior.

The results of Illich’s studies of the relationships between technology and our transportation, education, and medical practices can be generalized as a rule that in each technology, there exists a threshold of utility beyond which the technology becomes an end in itself.

Facebook was supposed to make it easier to connect with our friends. We could better connect with them by seeing what many of our friends are up to at a glance, we could organize parties easier, make fun comments without much effort and leave “likes” that show our appreciation for what they’re up to. But then people stopped making posts for their friends and started making posts for the likes. So much so that you can find endless examples online of degeneracy for the purpose of garnering likes.

Very recently, a minor TikTok celebrity more or less hijacked a train for social media attention.

<figure> </figure>

</figure>Another “streamer” harassed train passengers in Japan in order to gain the likes and comments of people he’s never met. He was confronted by a Korean American man from Texas on … he mistakenly assumed the man was Japanese and threatened him by saying: “Hiroshima, Nagasaki, you know? … We gonna do again.”

The point is, social media made us more connected (depending on your definition of connection, anyways) but at the same time it amplified a well known human tendency to misbehave for attention. Often, technology won’t just help you do the same things better, it will change how you do those things and may change your behavior patterns altogether.

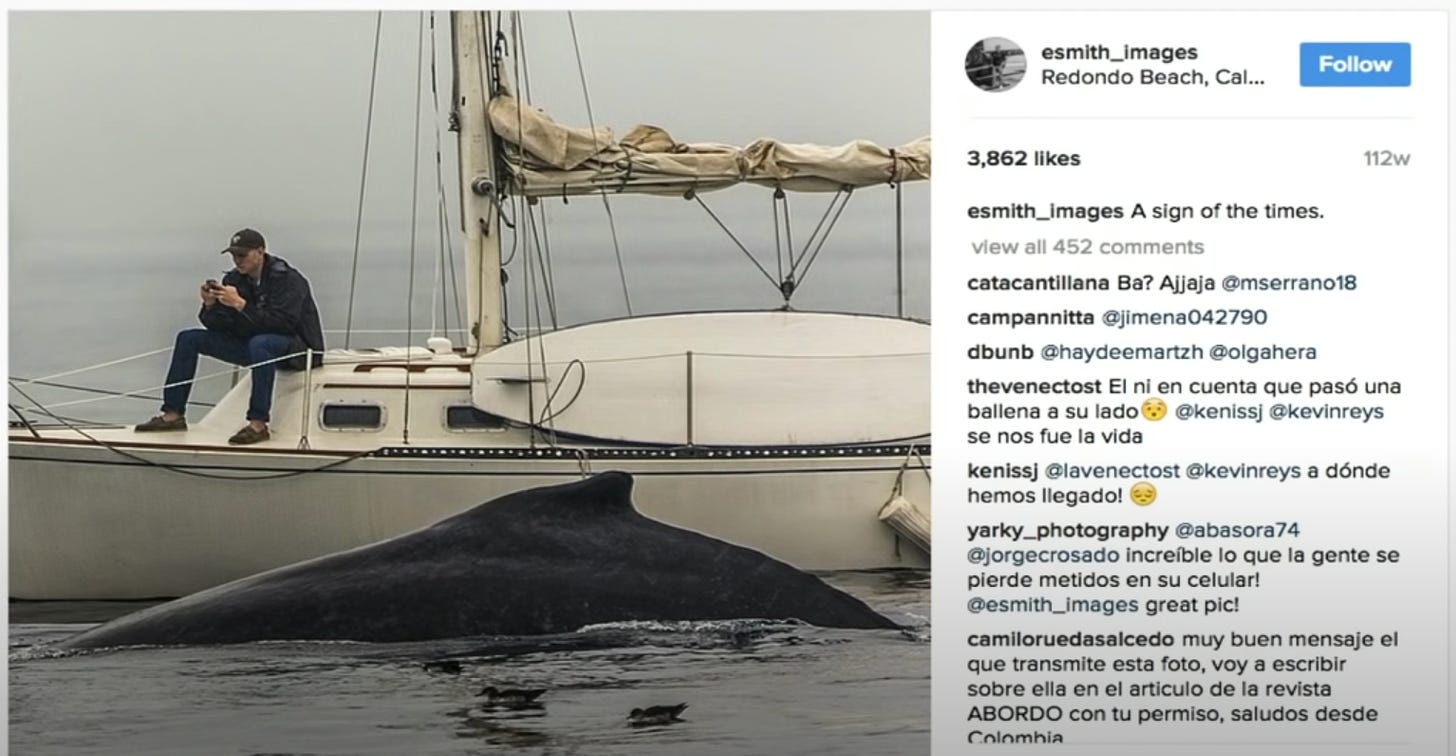

<figure> </figure>

</figure>In Nicholas Carr’s book The Glass Cage, he discusses how filling out patient information into a computer form has quite overtly changed the doctor-patient interaction. The doctor is not looking at the patient but at a screen most of the time, with the screen offering up boxes for the doctor to check that describe the nature of the patients’ ailments. This reduces the amount of meaningful interaction between the patient and literally steers the doctor to confining the nature of patients’ ailments to what matches the text prompts on the computer screen.

Once everyone has their own ChatGPT 7 rapidly deciphering and managing the cumbersome aspects of the world around us, we will be able to get what we want, faster and with less effort. How will that change our values?

<figure> </figure><figure>

</figure><figure> </figure>

</figure>In Adam Sandler’s 2006 movie Click, Christopher Walken gives him a magical remote that allows him to pause or speed up aspects of life as he sees fit. He could hit slow-mo on the big breasted woman going for a jog, pause time for his boss David Hasselhoff so he could slap him multiple times and fart in his face, and he could mute Terry Crews taunting him with a song in the middle of traffic, and he could speed up that tedious traffic so he wouldn’t have to experience the dull wait. That is, the technology in his hand gave him a superhuman ability to experience what he wants when he wants. (SPOILER ALERT) The heavy handed moral of the story is what you’d expect - Sandler cheapens his life by choosing not to experience the unexciting aspects of it and the immense dissatisfaction torments him on his deathbed.

<figure> </figure>

</figure>The problem with getting what you want

In a lecture at Harvard Divinity School, Peter Hershock says that:

“So what I’m referring to is a system that is a recursively amplifying wish fulfilling system that is designed to exploit human attention energy in order to realize previously unprecedented degrees of predictive certainty and behavioral control. It’s a new system for taking desires and translating those into responses to us individually. Individually targeting our values, our interests and our desires and feeding back to us as individual consumers and citizens precisely what we have asked for and wanted … and that’s why we should be worried.”

Why should we be worried about getting what we want? Isn’t that why we do anything, because we want something?

I think the issue is getting what we want too fast, with too little consequences and with too little effort.

<figure> </figure>

</figure>This is more or less the nature of video game or internet addiction. The amount of effort necessary to see something entertaining is so low that your brain says ‘might as well.’ When you’re deathscrolling Twitter, Instagram or TikTok or whatever, your brain runs a calculation of ‘is this amount of effort that this requires low enough to justify the amount of reward I can expect?’ and if it keeps getting a ‘Yes,’ your natural tendency is to keep deathscrolling. I will spare you the explanation of the hedonic treadmill and dopamine’s role in addiction (you can watch this for a more thorough explanation), but as you probably understand already - the more frequently we engage in behaviors that provide some sort of reward or stimulation without much effort (TikTok, video games), the less effort we are willing to exert on “slower” things in the future (participating in sports, writing, reading, creating things etc). A teenage boy may become less motivated to develop the social skills necessary to get a girlfriend the more he watches internet pornography.

Funny enough, I spoke about this in my first ever Youtube video 6 years ago in the section It’s addictive, but I’m not addicted:

"People pursue success in business, fitness or relationships mainly because they are anticipating some reward - usually a good feeling that comes with achievement. ‘But why work towards these types of fulfillment for so long when you can invest a couple seconds snorting cocaine or taking some pill?’ Surely a terrible mindset, but not completely different from getting the rewarding delicious flavor of a donut immediately, rather than chasing the great feeling of women complimenting your hard earned six pack. Or even swiping through a couple profiles on tinder to feel excited when you see a sexy girl versus investing a couple more minutes to read a chapter of that book you like. When you look at it like this, the idea of not just substances, but behaviors being addicting is more plausible."<figure>

</figure>

</figure>Later in his lecture, Peter Hershock says

“To get better at getting what we want, we have to get better at wanting. And to get better at wanting, which is a sense of feeling of lack, missing something, needing something we don’t have, then we can’t ultimately want what we get. The Karma of craving that forms a desire is the karma of continual dissatisfaction - of continual feeling of want and lack.”<figure>

</figure>

</figure>This ‘wanting’ leading to ‘getting’ leading to ever more ‘wanting’ reminds me of Tantalus. In Greek Mythology, Tantalus’s punishment was to be made to stand in a pool of water with fruitful fig tree branches surrounding him. Whenever he would reach for a fig, it would evade his grasp and when he’d bend down to drink the water it would recede.

The way we want has changed

In Peter Hershock’s Reinventing the Wheel, he says:

Once initiated, a technological lineage involves a co-evolution of useable and useful tools and patterns of wanting. Perfecting a technology is thus a way of perfecting—bringing to completion—a style of valuation, a particular fashioning of likes and dislikes. Because they are not things but forms of relationship, by changing our conduct, technologies necessarily take part in transforming not just what we desire, but who we are in our desiring.<figure>

</figure>

</figure>Nowadays, we want everything from furniture to food to coffee to entertainment to respect, money, fame and societal change quicker and with less effort. In short, by getting more of what we want and more of what we didn’t know we wanted, we have become ‘better at wanting.’ This of course is called impatience.

<figure> </figure>

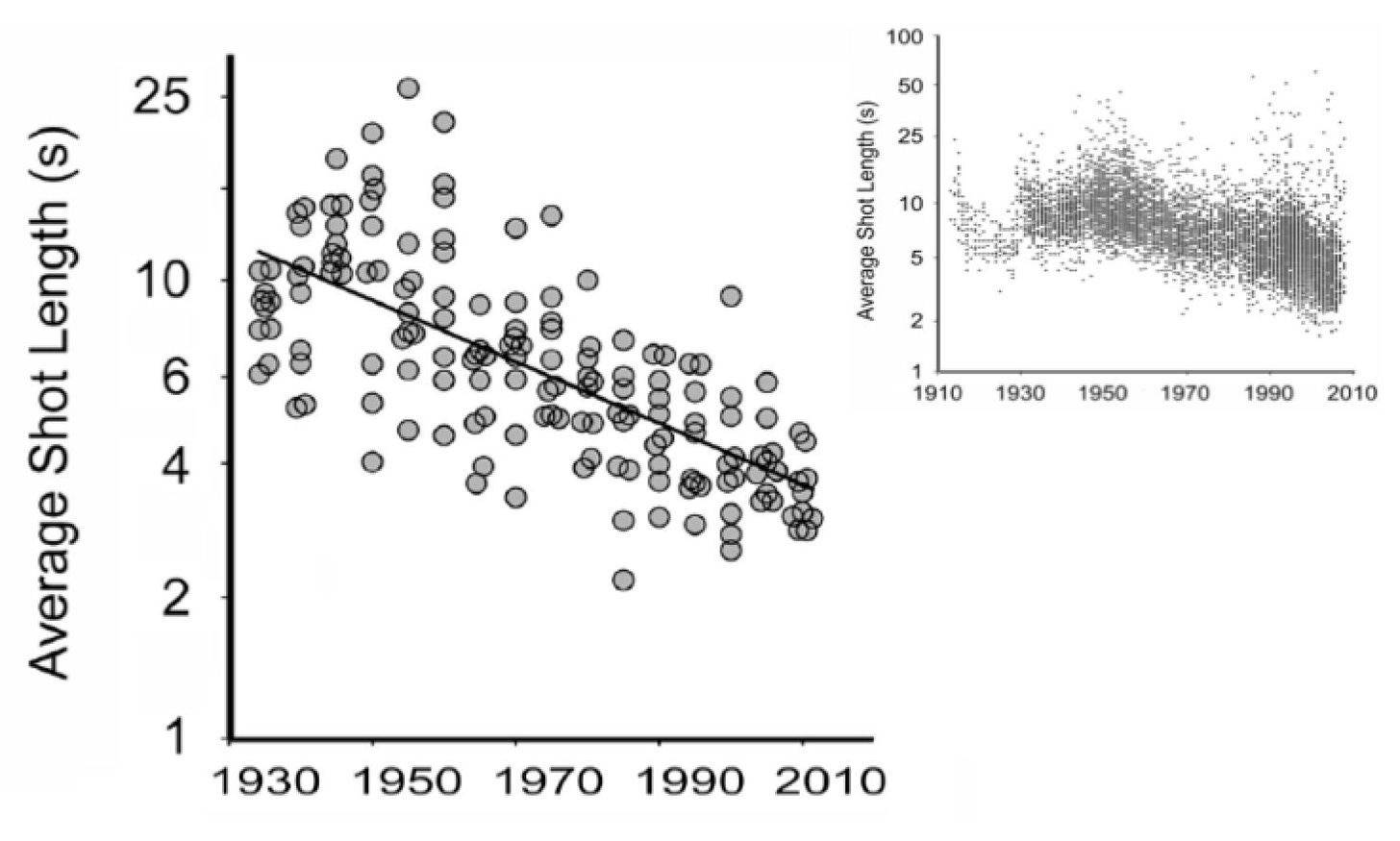

</figure>In 2014, Wired published an article titled Data from a Century of Cinema Reveals how Movies have Evolved. It focuses on psychologist James Cutting’s analysis of changes in cinema.

What stood out to me was that, as you can see in the image above, the average shot length in movies has about halved. In fact, in my own Youtube channel you can observe the increase in pace simply by watching my first video and my most recent video. My editing style changed not only because I found that a faster paced video seemed to perform better (depending on the topic), but because I myself enjoyed and preferred faster paced videos. Unsurprisingly, being exposed to content that delivers what I want faster caused me to become impatient with slower content.

<figure> </figure>

</figure>In Gary Wilson’s TedX talk, he points out that papers on internet addiction have been popping up even since 2009. He explains that:

“Constant novelty at a click can cause addiction.”

Of course we all know that, because that’s exactly what deathscrolling is. You swipe your thumb and you don’t necessarily get something good but you get something new, and you get it quickly.

<figure> </figure>

</figure>Unsurprisingly, one paper titled Examining the short-term effects of video exposure on children’s attention and other cognitive processes found that fast-paced children’s shows with many cuts per minute has a detrimental effect on children’s attention span.

Manoush Zamorodi claims in her TED talk that: “A decade ago, we shifted our attention at work every three minutes. Now we do it every 45 seconds and we do it all day long.” Near the end of the presentation, she said: “If you have never known life without connectivity, you may have never experienced boredom.”

<figure> </figure>

</figure>For better or worse, our brains quickly adapt to the pace at which things work out for us. We then become impatient when things don’t meet our new pace. I have a pair of Apple Airpods and they’re quite magical - they automatically connect to my phone the moment I take them out of their case without having to push a button or select the device on my phone. Sometimes they will automatically connect to my computer when I open it, which disconnects them from my phone and the music I was listening to suddenly stops. My magical technology not working exactly how I wanted it to causes a squirt of to irritation bubble up in my neck and I may even say say ‘piece of crap’ to myself as I have to perform an entire three clicks to disconnect the Airpods from my computer.

<figure> </figure>

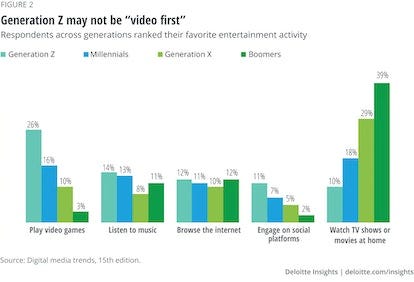

</figure>Movies are apparently not particularly entertaining for Gen Z-ers, they’d rather be playing video games. A DailyTelegraph article consulting psychologist Tanveer Ahmed claims that Children are ‘Unable to Watch a Movie’ because of TikTok.

This takes us back to Peter Hershock’s pointing out the problems of technology giving us exactly what we want. The internet has hijacked our attention span and made us more impatient people because we kept getting what we wanted.

It’s going to be difficult for human creators to compete with AI because algorithms (which seem primitive to upcoming AIs) already know what you want before you know it. For those of you using Youtube, how many of you use browsing features for most of your watching? If you search for a certain type of video you’ll probably find what you want. However, the recommended feature has an idea of what you want before you’ve even thought of it. My browsing feature is pretty good. Most of the time there’s at least one video that appeals to me that I in fact go on to watch. What happens when there is an AI that knows your reading habits so well that it can generate books from scratch that scratch just the type of literary itch you have?

<figure> </figure>

</figure>Money for nothing and your chicks for free

Becoming more impatient and dissatisfied with our entertainment is one thing, but the desire to actually do something productive or create value can pull people away from cheap rewards like that. But what about when producing becomes cheap?

<figure> </figure>

</figure>Well, that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Youtube is a great example of cheapening production. Without the connections or resources necessary to get your content on TV, people had no way to broadcast themselves or their content to a large audience. Once it started to become the norm for everyone to have internet access and a smartphone with a great camera, pretty much anyone had a chance on Youtube. Youtube was and continues to be flooded with all kinds of content, anything from toxic, depressing or just plain boring to educational, motivating or entertaining. Now, everyone has a chance to be successful in broadcasting.

So one thing we should expect to see from the advent of ChatGPT and its code writing abilities is a flood of people making and selling their own apps. In fact, I think a whole new wave of Youtube channels will come on the scene because the amount of effort necessary to make a reasonably watchable video continues to reduce. ChatGPT can quickly write you a script or a top tens list of the best Indie Rogue-like games to play, ElevenLabs can make generate a quite convincing voiceover from a text input, RunWay Gen 2 can even make pretty decent visuals from just a text prompt. I don’t mean images like Midjourney generates, I mean actual videos. Take a look at this entirely AI generated commercial:

Once the magical sparking quilt of AI blankets the entire world, many things will become cheap - not only in terms of cost to produce, but in terms of perceived value. Like swapping antique hand-made walnut tables and chairs for something hastily chosen at IKEA, the digital and potentially physical world will be populated with so many things that are just … cheap and forgettable.

Considering that in 2021, IKEA was the most valuable furniture retail brand at a value of over 21 billion USD, it makes you wonder if this is necessarily a bad thing. While IKEA’s optimizing of speed and quantity over quality was great for them and perhaps the consumers (especially college students), it wasn’t so great for antique sellers. By 2017, prices for antiques had dropped to their lowest levels since the 1930’s. We can bet that OpenAI and other companies developing AI’s that drastically lower the bar to being able to make decent code will make tons more money, but the average salary for programmers will probably reduce. By the same token, those people that hire developers to create apps for them will expect better apps for cheaper and delivered faster.

AI will raise the bar for everyone. AI may drastically reduce the tedium in our lives by doing all kinds of boring tasks for us … but it will do this for everyone. An influential number of people will use the efficiency afforded by AI to produce more, not produce the same amount with less effort.

You may have to exert the same if not more effort to be relevant enough in the marketplace to receive pay that is above average. Based on my experience with Youtube, I’m guessing having a cool thumbnail for this Substack article will be important to getting people to click on it by making it stand out. Luckily, I have Midjourney that can make pretty fantastic images just from a text prompt. Though, pretty soon all Substack writers will wise up to the fact that they can make compelling thumbnails with a mere text prompt and I’ll be right back where I started and will have to once again spend extra time and effort on my Substack thumbnails.

If AI is constantly yielding more and more amazing things for us faster and faster, it’s likely to make us more impatient people. With our patience eroded, will it be more difficult to exert that effort necessary to get a leg up in the marketplace? It may not just be our patience that is eroded. We may be losing the patience and the skills to compete with AI.

<figure> </figure>

</figure>Smarter AI, Dumber Humans

Nicholas Carr’s 2010 book The Shallows expands on the concepts set forth in this 2008 article Is Google Making us Stupid? In the book he tells the story of how Igloolik Inuit hunters are losing an ancient technique for safely navigating across miles of ice and tundra to track down their food. The barren Arctic terrain offers few landmarks and quickly erases any trails, yet to the amazement of scientists and explorers, Inuit hunters have been able to find their way for centuries. Igloolik hunters learn to navigate the terrain by dedicating themselves to developing a profound understanding of winds, snowdrift patterns, animal behavior, stars and tides.

Yet, things have become much easier nowadays thanks to GPS technology. The thought of older Inuit harping on the younger ones about how they need to learn way finding techniques of their elders reminds me of how my grade school teachers would tell us that we need to learn our maths because we’re not all going to be carrying calculators in our pockets.

Yet along with the proliferation of GPS devices came reports of serious accidents during hunts. It’s annoying but not a big deal when the little blue dot in Google Maps on our phones misleads us into thinking we’re at our destination but we’re actually a block over. However, getting lost in the arctic tundra when a GPS receiver fails is much more than annoying. Being misled can be a matter of life or death.

“The routes so meticulously plotted on satellite maps can also give hunters tunnel vision, leading them onto thin ice or into other hazards a skilled navigator would avoid.”

The moral of the story is use it or lose it. As we delegate certain tasks to machines, we lose certain abilities.

Carr gives another example of pilots relying too heavily on their planes’ autopilot systems. Some plane crashes have been due simply to pilots doing the wrong maneuver when the autopilot needs to be disconnected and they have to manually fly the plane.

Automation has become so sophisticated that on a typical passenger flight, a human pilot holds the controls for a grand total of just three minutes. What pilots spend a lot of time doing is monitoring screens and keying in data. They’ve become, it’s not much of an exaggeration to say, computer operators.And that, many aviation and automation experts have concluded, is a problem. Overuse of automation erodes pilots’ expertise and dulls their reflexes, leading to what Jan Noyes, an ergonomics expert at Britain’s University of Bristol, terms “a de-skilling of the crew.”<figure>

</figure>

</figure>Will essaysists become ChatGPT operators? Are artists going to become Midjourney operators?

While it did take about 60 prompts to get something that felt right, my most recent video’s thumbnail is entirely generated by Midjourney, all I did was add the text. I always thought I was pretty decent at making thumbnails, but did I rob myself of the chance to improve and maintain my thumbnail making ability by offloading the entire process of making that thumbnail to AI?

(On that note, none of this article was generated by ChatGPT)

Unemployment for nothing, droids for free?

“Work spares us from three evils: Boredom, Vice, and Need.”

-Voltaire

In a TED talk from 10 years, ago Andrew McAffee said “Just in the past couple years, we’ve seen digital tools display skills and abilities that they never ever had before and that kind of eats deeply into what we human beings do for a living.”

He goes on to talk about Siri, multilanguage instantaneous translation services, IBM’s supercomputer Watson beating out other contestants on Jeopardy!, autonomous cars, DARPA’s robotics challenge and so on. (Remember this is 10 years ago)

“But in the not too long term, within the lifetimes of most of the people in this room, we’re gonna transition into an economy that is very productive but that just doesn’t need a lot of human workers.”

McAfee explains that the employment situation for the Teds and Bills of the world are drastically different. Ted represents the college educated; manager, doctor, lawyer, engineer, scientist, professor or content producer. Bill represents the no college; blue-collar, service, or low-level white-collar worker.

<figure> </figure>

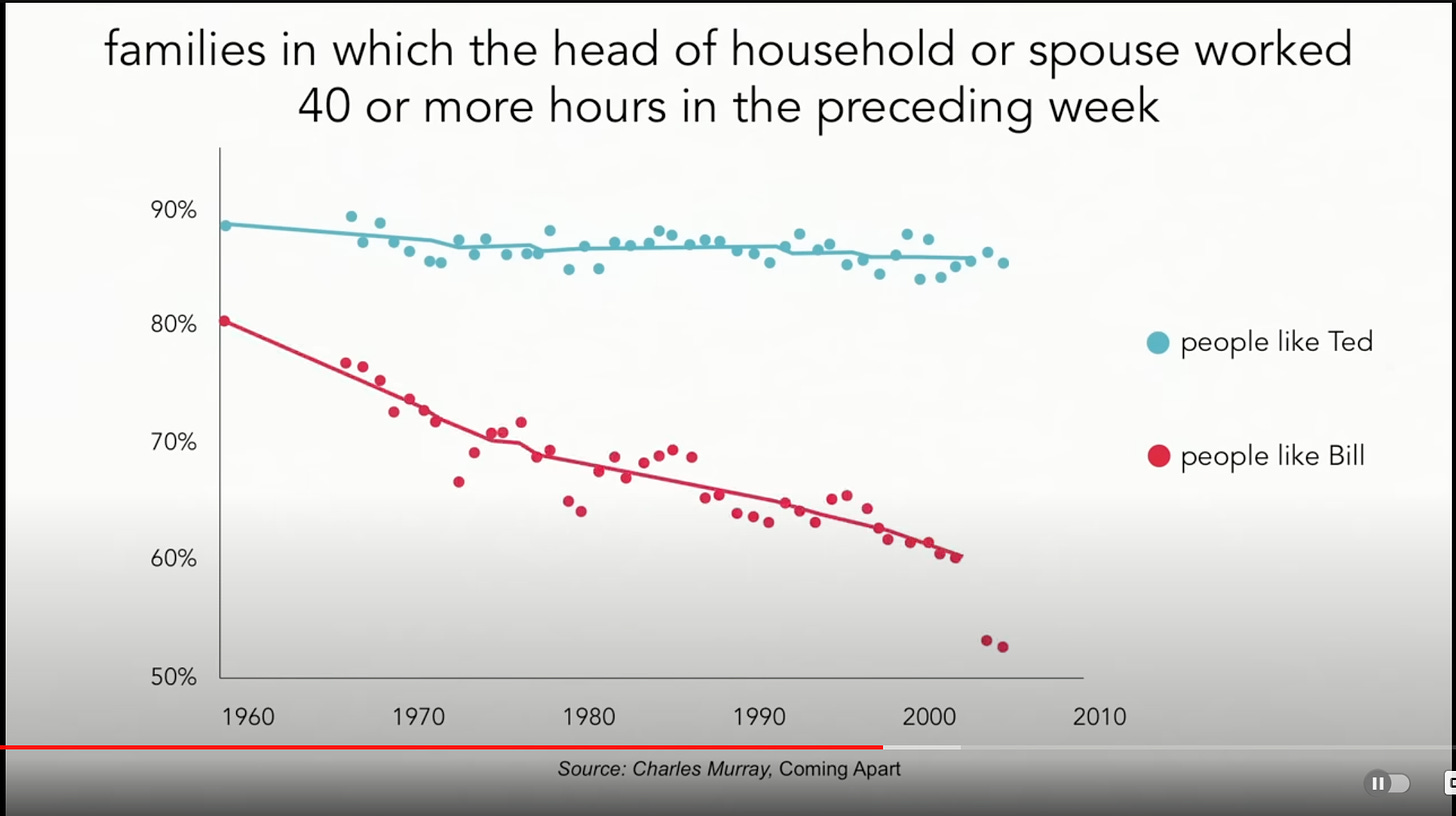

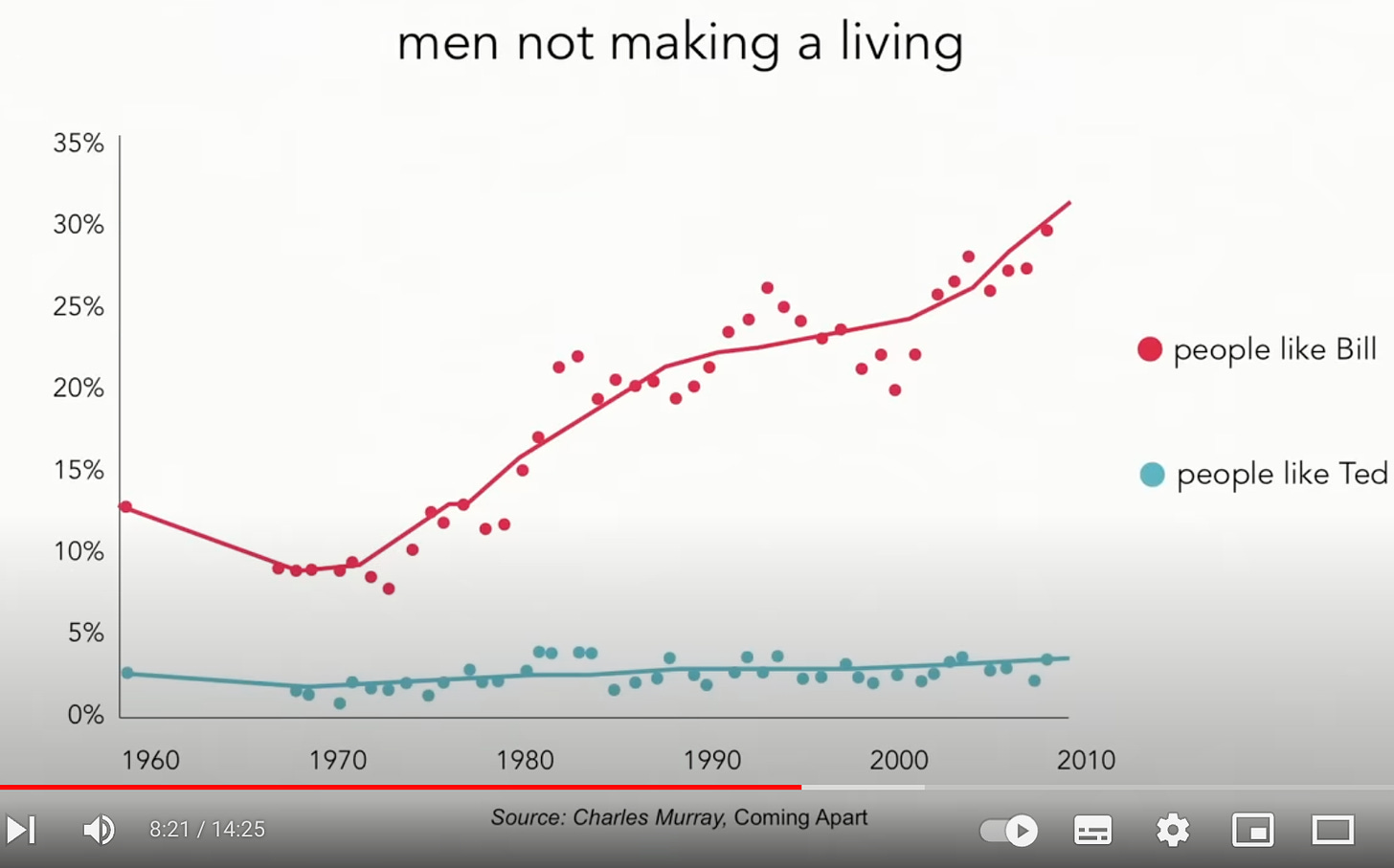

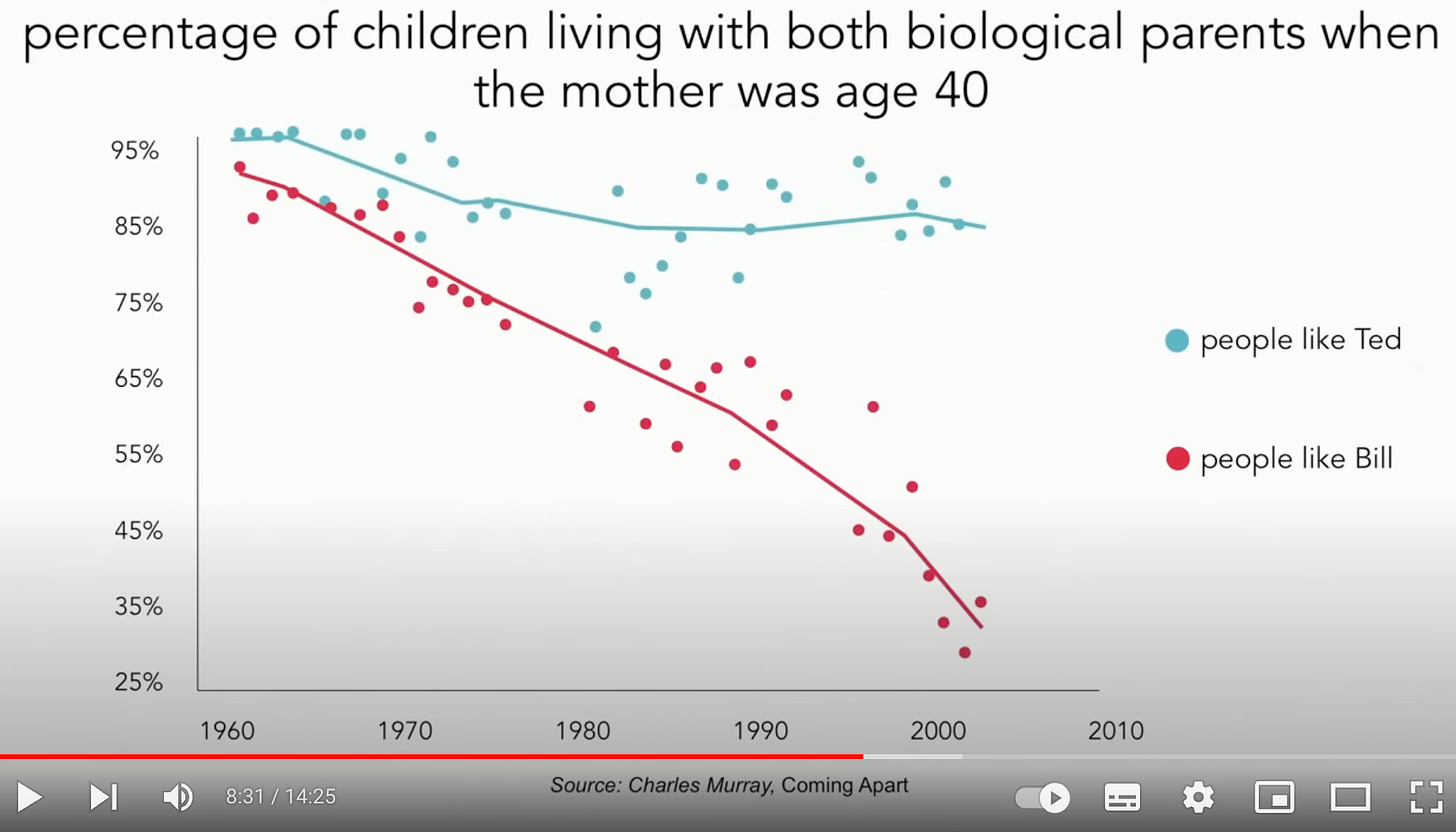

</figure>He shows three charts that illustrate that the Bills of the world have less work nowadays and are experiencing more divorce.

<figure> </figure><figure>

</figure><figure> </figure><figure>

</figure><figure> </figure>

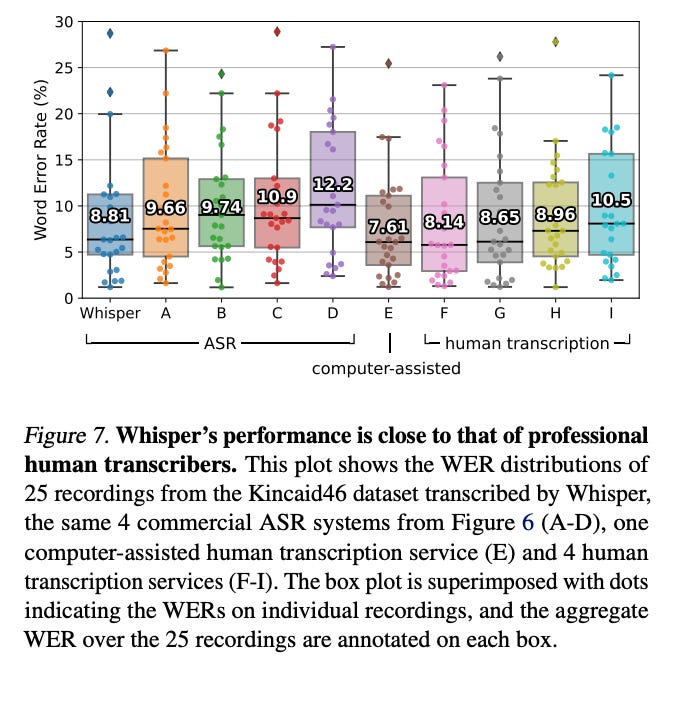

</figure>ChatGPT has "performed at or above the median performance of 276,779 student test takers on the Medical College Admission Test.” We have Midjourney as you’ve seen and, Reuters claims lawyers should be afraid of ChatGPT taking their job, AI is diagnosing heart attacks better than humans, and AI is better than some humans at transcription. So maybe the Teds of the world will suffer a fate similar to the Bills of the world.

<figure> </figure>

</figure>So, what do we do?

Unsurprisingly, we can expect AI to soon be seamlessly integrated into our society. Commenting on the observations by Ivan Illich, Peter Hershock points out that “once we cross a technology’s threshold of utility, what was once only ‘possible’ becomes ‘necessary’.” It used to be that people’s place of work was arranged based on the fact that we didn’t have means to easily traverse large distances with ease. Now of course, our lifestyles are arranged based on that the fact that we have cars and trains. Again, technologies don’t just assist our lifestyles, they change them. Elevators didn’t just save us some effort, they enabled a whole new type of architecture, changed city dynamics and our culture. Nowadays, for most people it’s a necessity that they have access to a car or public transport and to have internet access to be able to live their lives.

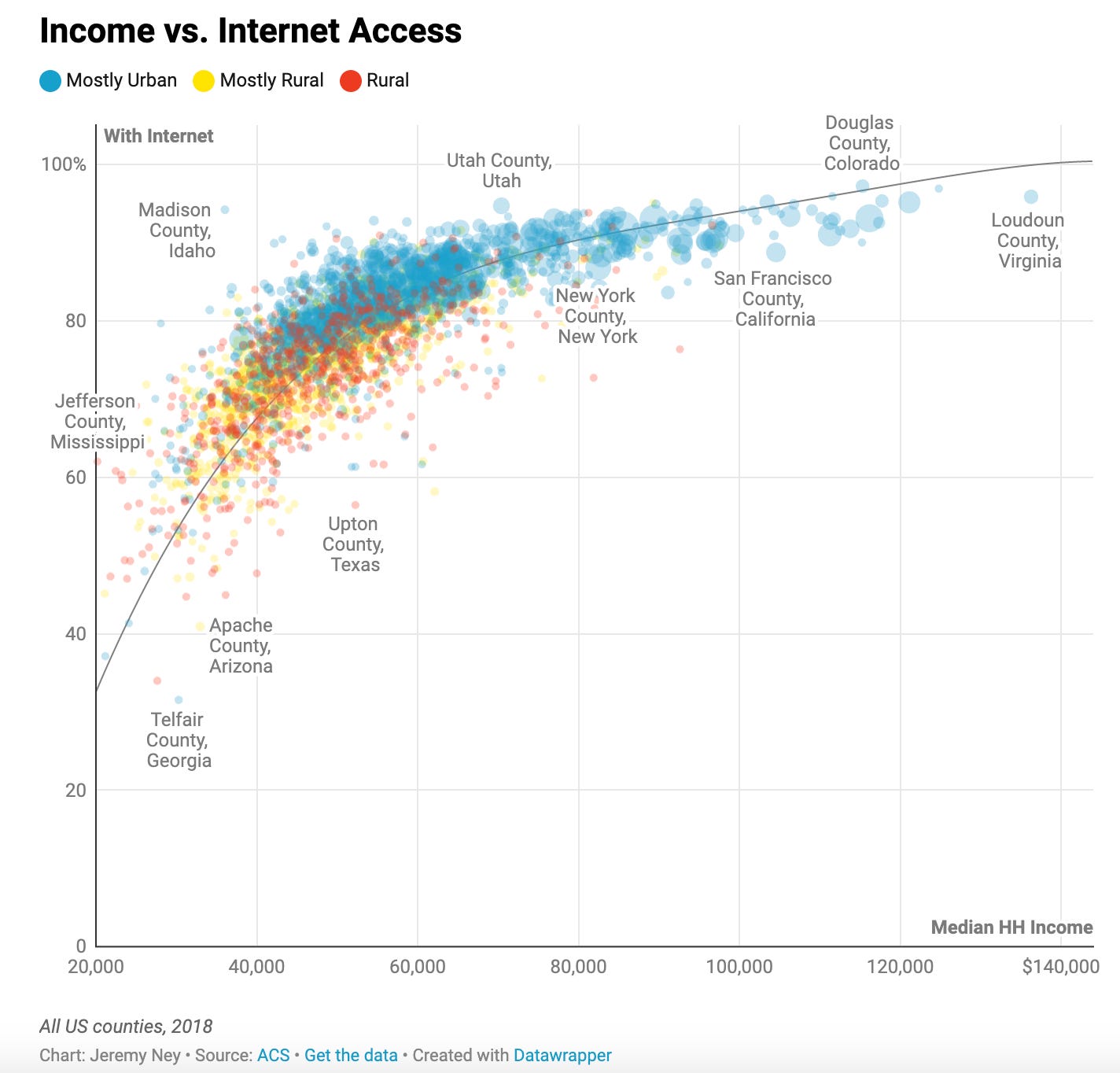

<figure> </figure>

</figure>It may not be neccessary for some that they adopt a certain technology, but it will certainly be advantageous. The above image from Jeremy Ney’s article on Internet Access and Inequality shows an unsurprising relationship between internet access and income. Areas with more internet access have a higher median income. We should expect a similar trend with adoption of AI.

It’s almost certainly the case that in general, the people who become more effective users of AI will have much higher earning potential. This is to say that we will have to exercise the mental discipline to become adept users of AI whilst not letting it erode our minds.

You might think that that is exactly what I have done with Youtube. That I avoid all the negative aspects of Youtube while just using it for my benefit by watching educational videos and lectures and making a living off of it. However, I am not that effective at evading Youtube’s erosion of my mind. I’m practically always consuming content - whenever I’m walking to the cafe, to the gym, to the supermarket or even when I’m just washing the dishes, I’m listening to or watching some video. I procrastinate on my work by telling myself that the content I’m watching will help me come up with more interesting points for my articles or my video scripts, but at the end of the day I forget a majority of what I listen to. To actually make use of the information, I should be balancing time consuming content with time spent allowing my mind to become bored and make interesting connections between the chunks of information that I’ve ingested.

The good thing is that when I dig myself into these pits of excessive content consumption, I know how to dig myself out. The solution to the mind being intoxicated by speedy experiences delivered by technology is simply to do more slow stuff. Spend more of your time reading books, going to the gym (and less watching videos between set), taking walks with your friend or spouse and so on. Better yet, do one of the slowest things of all: investigate the quality of how your mind operates by meditating.

So what?

“So what?” is the title of the last chapter of Peter Hershock’s book. He says:

The bald fact of the matter is, we are not going to give up our cars, our refrigerators, our air conditioners and heaters and electric lights. We are not going to dismantle our computers, televisions, and radios. … For better or worse, for richer or poorer, we’re locked in. The lives we lead and call our own depend on the successes of our various technologies and the control they afford us. …If we are to resist the colonization of consciousness… we must free ourselves from the knot of our own wanting and satisfaction.

At the risk of cheapening his message by extracting the “point” from the 278 pages of context he provides, he basically says that the solution is to meditate.

Hershock’s book was part of the reason I felt compelled to do a 10-day meditation retreat which yielded some results that slightly resembled what I thought could only happen in Buddhist fairy tales. If that piques your interest, take a look at my series Is Enlightenment Real?