Inventing the Roleplaying Game (Part 1): The First "Game Master" | Preview (Patreon)

Content

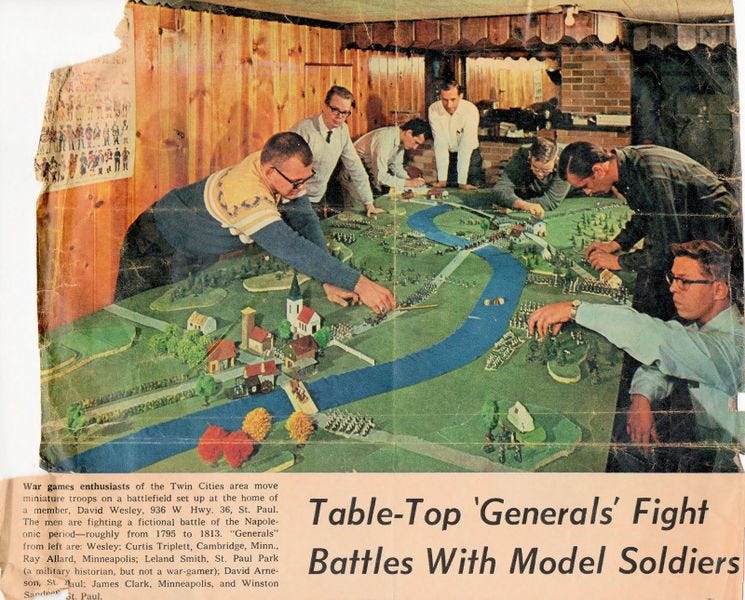

A while back, I sat down with a good friend of mine, Joe DeSimone, to learn about the history of the tabletop roleplaying game (TTRPG) genre and its origins in the 1960s American wargaming scene (this happened during an episode of Anything But D&D for long-time Patrons). While discussing the influences of tabletop wargames such as Strategos by Charles Totten (1880), Siege of Bodenburg by Henry Bodenstedt (1967), and Chainmail by Gary Gygax and Jeff Perren (1971), the topic of one of the lesser known influences on the history of the hobby came up - the “Braunstein”.

The First “Game Master”?

At their core, TTRPGs involve players assuming the roles of fictional characters and collaboratively create a story. The action is described primarily through spoken word and the outcomes are often determined by formal rules arbitrated by a referee and dice rolling (though there are dice-less games that use tools like playing cards or a Jenga tower).

In the west, Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) is synonymous with tabletop roleplaying games as a hobby. However, while Gary Gygax and David Arneson are credited as the creators of D&D in 1974, it would be incorrect to say that they created the practice of tabletop roleplaying - the roots of which trace back to tabletop wargames like:

- Strategos by Charles Totten (1880)

- Modern War in Miniature by Michael F. Korn (1966)

- Siege of Bodenburg by Henry Bodenstedt (1967)

- David Wesely’s Braunstein* (1969)

- Chainmail by Gary Gygax and Jeff Perren (1971)

And board games like:

- Outdoor Survival by Jim Dunnigan (1972)

- Dungeon! by David Megarry (1975)

*Note: Wesley’s creation is often referred to as “the Braunstein” (i.e. a game) or “a Braunstein” (i.e. a game genre).

Korn’s Modern War in Miniature is often attributed by scholars as the game that set the precedent for a dialogue between players and a referee. But it’s Wesely’s Braunstein that is commonly credited as the first game to emphasize personal interactions and setting context over complicated mechanical rulings.

Unlike the popular wargames of the 1960s and 1970s, which saw players command armies on the table, the Braunstein took a radically different approach. The first was in it's setting. The first Braunsteins (meaning “brown stone” in German) were set in a fictional town of the same name between conflicts. The second was in the role of the players. Instead of controlling large, faceless armed forces, each participant took on the role of an individual character - usually an important inhabitant of the town with their own goals and agendas.

In an archived post on Acaeum, Wesely outlined his inspirations for the Braunstein.

The first was Strategos (1880), a wargame by Charles Adiel Lewis Totten that was designed to as a training tool for the United States Army. In the 1960s, the game had fallen into relative obscurity until it was rediscovered and repurposed by Wesely for the miniature wargames played by the Midwest Military Simulation Association (MMSA).

*I have tidied up the spelling from quotes of his post for the sake of readability and provided context in parentheses.

“The idea of having an all-powerful Referee who would invent the scenario for the game (battle) of the evening, provide for hidden movement and deal with anything the players decided that they wanted to do was not taken from Kriegsspiel [a genre of wargaming with roots in the historical Prussian Army used to teach battlefield tactics] but was mostly inspired by 'Strategos, The American Game of War', a training manual for US army wargames [First] Lt. Charles Adiel Lewis Totten, USMA 1871, published by Doubleday in1880. We had found a copy in the U of Minn [University of Minnesota] library and I had tried to adapt it for Napoleonic Wargames ('Strategos-N') before Braunstein.”

The next was The Compleat Strategist (1954) by J.D. Williams. This is an accessible resource on games strategy theory that is still free to download from the RAND Corporation. Following that was Conflict and Defense: A General Theory (1962) by Kenneth E. Boulding.

“I created all the non-military roles for the first Braunstein game, not because I had too many people for the game, but because I had become interested in the concepts of n-player [finite and defined number of players] strategy games (where N is > 2) discussed in Kenneth Swezy's [he confused J.D. Williams and Kenneth E. Boulding] book about the theory of games 'The Compleat Stategist' and of overlapping and conflicting, but not directly opposite, objectives laid out in 'Conflict and Defense' (sorry, I've forgotten the author of that one) [Kenneth E. Boulding]. The latter were the only books on "games" or "strategy" in our college library in 1963.“

Unlike the popular war games of the time, Wesely’s Braunsteins were fairly unstructured for a tabletop gaming experience.

“I thought of the "wacky" roles as a joke on my players, and did not expect we would be repeating my multi-objective game any time soon. However, the players were of a different mind, and after two flops, when I realised that the key was letting the players try to do whatever they wanted, and not worrying about how to score the game, we started playing a lot of "Braunsteins" (no one ever called them MOGs [multi-objective games] again).”

This, however, proved to be very influential to the trajectory of the hobby. David Arneson would later marry the miniature-based rules of Chainmail with roleplay elements inspired by the Braunsteins that he participated in. He received wider attention of his efforts after he published Facts about Black Moor. Arneson’s creation of Black Moor would then lead to the collaboration with Gary Gygax that resulted in the creation of D&D.

<figure>David Wesely (left). Source: RPGgeek.com </figure>

</figure>Despite the immense influence the Braunstein would have on the future of tabletop roleplaying games, Wesely himself wouldn’t categorize it as such.

”By the way, I did not like the term "role-playing game" when it appeared, as "role playing games" that had nothing to do with what we were doing, already existed: The term was already being used for (1) a tool used to train actors for improvisation (an example being the Cheese Shop Game [referring to the sketch from Monty Python's Flying Circus] since immortalized by Monty Python) and (2) a tool used for group therapy and psychiatric analysis…I favored "Adventure Game" but that was seized-upon at the time as a replacement for "Hobby Game" or "Adult Game", and now we are stuck with "RPG".”

An Interesting Claim

Interestingly, in the same archived post on Acaeum, Wesely claims to have invented the use of polyhedral dice in tabletop gaming practice.

While I am beating my own drum, I would like to lay claim to having "invented" polyhedral dice. I was the first person to USE what were then being sold as "Models of the five regular polyhedra" (for mathematics teachers to show to their students), AS DICE. I have since seen a book that claims that the Japanese were already using three D-20s, numbered 0-9 twice, to generate 3-digit decimal random numbers at some time before 1976. So it may be that they also invented this use for polyhedra, but I was unaware of them so I am at least an independent re-inventor. And it was my introducing the D4, D8, D12 and D20 to our gaming group in 1965 that led to them being used in RPGs and D&D.

This is factually incorrect, as there have been several patents involving polyhedral dice. For instance, Fredda F. S. Sieve filed a patent on February 20, 1963 for a “Dice game with a tetrahedron die“. The dice were required for a game of her invention called Zazz (details on it can be found on Playing at the World).

<figure>Details on this patent can be found here. </figure><figure>Fredda Sieve (R) in March 1960 and a Zazz set (L) - Source

</figure><figure>Fredda Sieve (R) in March 1960 and a Zazz set (L) - Source </figure>

</figure>Before Fredda F. S. Sieve, the icosahedron die (the d20) with 0-9 numbered twice was invented by Yasushi Ishida (Japanese patent no. 195222, utility model no. 404183) and distributed by the Japanese Standards Association in Tokyo, Japan. Though, we have certainly seen icosahedron appear in the archaeological record (such as this one rediscovered in Egypt from the Ptolemaic Period to Roman Period).

<figure>Image source: Dice Collector </figure>

</figure>So how is a Braunstein played?

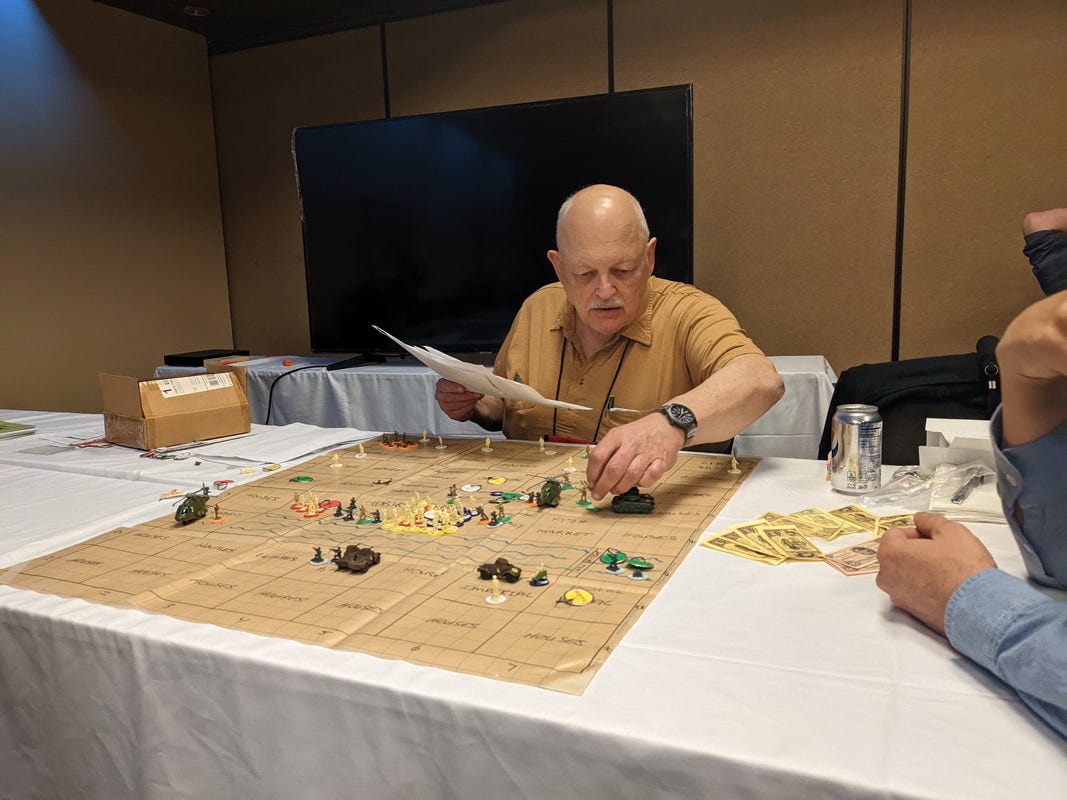

<figure>David Wesely refereeing a Braunstein at Gary Con 2022. Image source: Secrets of Blackmoor. </figure>

</figure>The original rules of Wesley’s Braunstein were often in flux, but had some common characteristics:

- Despite the German name, a Braunstein can be set anywhere. A well documented first hand account of a Braunstein refereed by Wesely at Gary Con 2022 was set in the 1950s in the fictional South American country of Banania.

- Maps, tokens, miniatures, and terrain are not required, but are commonly used to visualize the progress of the scenario.

- Players are given or may choose from a roster of pre-generate characters with established objectives and motivations that are required to “win” the scenario - these typically aren’t accomplishable by a lone character. These objectives may put a character at odds with another, or require them to form alliances. Individual objectives for a character may conflict with one another. Multiple players can win the game if their objectives do not overlap or end up involving an alliance.

- Characters have varying degrees of importance to the scenario developed by the referee. This allows players to join late (i.e. as backup characters) or for people of different comfort levels to participate.

- The primary means of interaction are player character-to-player character, with very few non-player characters. During the session, players can even leave the room to scheme in secret.

- Braunstein’s have very few actual mechanics, taking a free Kriegsspiel approach and allows the referee to arbitrate the game. Another account from Gary Con (referring to 2017 or 2018) noted that, apart from the character handouts, rules or reference sheets were not present.

- After the scenario is presented by the referee to the players, players are free to talk to other players as they strive towards their individual objectives - forming alliances (genuine or not), making mock threats, jockeying for information from others, etc. After a predetermined amount of time for a “turn”, each player turns in written orders for their character that the referee reads, interprets, and executes (in the style of Kriegsspiel wargames).

To me, Braunstein’s appear like a LARP combined with large group wargames!

An accessible Braunstein?

I had to try playing a Braunstein, or something as close as I could get.

The most accessible and comprehensive resource I could find was Barons of Braunstein, a TTRPG written by James and Robyn George that is inspired by the original Braunstein and officially licensed by David Wesely. The product page on DriveThruRPG even includes a supplementary essay for playing in a traditional Braunstein written by David called Braunstein in the Middle Ages. Once I can get a group together, I’m going to try playing it!

<figure> </figure>

</figure>So what’s next?

In 2006, Wesely noted that he isn’t technically the only inventor of the tabletop RPG.

“…in 1968 [it was actually first published in 1966], Michael J. Korns published "Modern War in Miniature", a set of miniature rules with all of the features of an RPG, and he and I had never met. While Braunstein pre-dates Korns' rules, it is only fair to say that he also invented the RPG.”

That said, it’s only fair that an examination of Modern War in Miniature should come next!

References

Playing at the World: A History of Simulating Wars, People and Fantastic Adventures, from Chess to Role-Playing Games by Jon Peterson

Strategos: a series of American games of war by Charles Adiel Lewis Totten