Part 2: Reading the Finalists in the 2023 Hugo Award for Best Graphic Story Category (Patreon)

Content

by Doris V. Sutherland

Welcome to the second of a two-part series reviewing the finalists for the 2023 Hugo Award for Best Graphic Story. The present post will cover Supergirl: Woman of Tomorrow by Tom King, Bilquis Evely, and Matheus Lopes (DC Comics), Cyberpunk 2077: Big City Dreams by Bartosz Sztybor, Filipe Andrade, Alessio Fioriniello, Roman Titov, Krzysztof Ostrowski (Dark Horse Books), and Dune: The Official Movie Graphic Novel by Lilah Sturges, Drew Johnson, Zid (Legendary Comics).

Supergirl: Woman of Tomorrow

Although the title character here is Supergirl, the story begins neither in Metropolis nor on Krypton, but on another world entirely; a world dominated by swords and arrows. The narrator is Ruthye, a young girl whose father has been murdered by a rogue named Krem of the Yellow Hills after an argument over the new king. Taking Krem’s abandoned sword, Ruthye sets off hoping to find a warrior who can use that blade to slay Krem.

Her first choice is a generic Conan-like barbarian, but this man promptly gets into a dispute with – and is bested by – a drunken blonde woman in a thick brown jacket. A woman whose undergarments turn out to be bright red and blue, and who goes by the name of Supergirl (or, alternatively, Kara Zor-El).

The two travel until they encounter Krem of the Yellow Hills, who gives fight. As this is a planet with a red sun, Supergirl lacks her usual invulnerability. She herself survives the encounter despite an injury, but her dog Krypto is seriously hurt when Krem hits him with a poisoned arrow. Krem escapes into space, and his two pursuers begin a joint mission to track him down: Ruthye still desires her revenge, and Supergirl needs to find an antidote to save the life of Krypto.

The central creative team of Supergirl: Woman of Tomorrow is artist Bilquis Evely, colourist Matheus Lopes and writer Tom King, and the last of these names will be familiar to anyone who keeps up with the Hugos’ comic category. Although King has never penned a single series that became a Hugo fixture in the way that Saga, Monstress or Once & Future have done, his superhero series evidently appeal to Worldcon voters: his take on the Vision for Marvel was a finalist in 2017, while his Strange Adventures miniseries for DC was in the running for 2022.

King is known for high-concept twists. In the case of Supergirl: The Woman of Tomorrow the innovation is that, while Supergirl is nominally the central character, Ruthye serves as narrator. This sounds like a small detail, but given the sheer density of these prose-filled caption boxes, it comes to shape the whole of King’s writing. At first, it serves to amplify the genre-clash of Supergirl ending up in a sword-and-sorcery world: a familiar four-colour superheroine being described by a narrator out of Tolkien or Dunsany.

As the story progresses, and the characters visit different worlds, Ruthye’s sardonic-pedantic tone takes on a new dimension. She becomes a cross between a snarky sitcom Goth and Alice, interrogating the logic of Wonderland’s inhabitants. Her general personality is summed up by an argument she has with an inconsiderate fellow-traveller on public space-transport.

“You’re small. Mm”, says the alien sitting rather too closely next to her. “Are you tasty?”

“For the life of me,” replies Ruthye, “I cannot fathom how my size and piquancy have any relation to the disputed matter at hand. Though I do assure you that any attempt to consume me will result in your humiliated surrender. For I do not travel alone, but am accompanied in my vengeance-quest by a warrior whose renown echoes from one side of the universe to the other. The Maid of Might. Supergirl. Who is currently seated to your opposite side.””

While the comic frames Ruthye (who describes things) and Supergirl (who does things) as representing two different genres – sword-and-sorcery versus sci-fi superhero – they have something in common in that they are both used to conflicts having easy solutions. For Ruthye, a murder can be readily avenged by slaying the murderer. Supergirl, while averse to outright killing people, is still a triumphalist figure who can quip and punch her way out of most situations. A few pages after the above-quoted spaceship dispute, Supergirl is accosted in a bar by a gun-toting alien with a grudge against the Superman family “Are you really Supergirl?” asks her opponent. “Well. Let’s see”, she answers. “I’m wearing a big yellow S on my chest. And a very fashionable red skirt. So if I’m not Supergirl… who the %@## do you think I am?” She proceeds to beat up the alien.

Such incidents may give the impression that Supergirl: Woman of Tomorrow is a tongue-in-cheek romp, but much of the comic is spent exploring heavy subject matter. Krem of the Yellow Hills turns out to have partnered with a crew of space pirates known simply as the Brigands, who have run a trail of destruction from planet to planet. The horrors wrought by the Brigands are explicitly presented to evoke real-world atrocities.

In one issue, Kara and Ruthye land on a planet with an Art Deco aesthetic suggesting the early-to-mid twentieth century, inhabited by blue, frog-like humanoids. Kara sees evidence of another race, one with purple skin, being segregated at some point in the past; yet even with her super-sight she is unable to see any purple aliens still living. When she visits a desolate area once known as Purpletown, she uncovers a mass grave.

Interrogating the blue mayor, Supergirl learns the full truth. The planet had been attacked by the Brigands; but the Blues, on the suggestion of Krem, were able to spare their own lives by handing over the Purples to be killed. The sequence is a bizarre but undeniably effective one, evoking real-world genocide imagery (particularly, given the overall 1920s ambience, the Tulsa massacre) but mixing in with the cute, cartoony designs of the blue-purple aliens and the fantastical steampunk of the Brigands, all illustrating a story told through Ruthye’s florid narration.

The issue concludes with Supergirl comforting Ruthye, whose view of human(oid) nature has been shaken. She has seen how the blue people were able to lead normal lives and treat each other with kindness despite having been party to genocide: all of this is a long way from her planet where wrongdoers are easily identified and can be safely slain with a sword. Notably, while Kara is drawn in this scene as the model of tenderness and empathy, she is given no dialogue. Supergirl, too, is facing tough questions.

It has to be said that, for some time now, Supergirl has been among the less consistently portrayed of DC’s big-name heroes (right down to the awkward existence of multiple canonical Supergirls). In Supergirl: Woman of Tomorrow, Tom King appears to have made it his mission to define the character. Although it may appear that Kara is being sidelined by Ruthye, the truth is that Ruthye acts as a foil so that Supergirl can establish herself in a coming-of-age narrative.

At the start of the story, Kara has just turned 21 and is celebrating by getting thoroughly drunk; here, we see the uncouth, smart-mouthed interpretation of Supergirl that goes back at least as far as her nineties riot grrrl incarnation, and which positions her as a rougher-edged counterpart to the eternal nice-guy Superman. When she teams up with Ruthye, however, Kara is forced to grow up. She becomes a mother-figure to the young girl, talking her through cultural standards that range from washing her hands after using the bathroom to not killing people.

There is a clear irony in that the well-spoken Ruthye is coded as being more mature than the drinking, swearing Kara. After all, Ruthye has been forced to grow up fast by the death of her father. But as the story comes to emphasise, Kara has been through a still greater loss: a key part of her backstory is that, unlike Superman, she actually remembers Krypton and its inhabitants from before the planet and its inhabitants were destroyed. The fact that the two main characters have both similarities and stark differences allows them to bounce off each other and eventually to grow together. An added irony is that, when Supergirl becomes incapacitated by Kryptonite, it is Ruthye who must act as caregiver.

The two basic driving forces of the Superman mythos are the fantastical possibilities of Kryptonian superpowers on the one hand, and an essential faith in human compassion and the achievability of justice on the other. Both traits are on show in Supergirl: The Woman of Tomorrow, although the comic knows when to embrace such optimistic fantasy and when to keep it tempered.

One vignette has Supergirl encounter a towering, Jack Kirby-esque alien seemingly bent on destruction for the sake of destruction; but it turns out that this alien has lost her family to the Brigands, and has found herself incapable of mourning: violence has become her only conduit. The encounter ends with the alien and Supergirl embracing for a moment of shared tenderness. During her voyage, Supergirl’s powers can constrain as well as liberate. Shortly after the above incident, she visits a citadel of glass filled with the remains from another Brigand attack, and she is unable to stay. If she stays, then she will scream; and if she screams, then the entire glass citadel will shatter.

All of this presents an imposing task to any artist tasked with drawing it. Bilquis Evely, who provided the black-and-white art with Matheus Lopes colouring, was required to draw a multitude of worlds – all distinct yet with a strain of aesthetic consistency – and populate them with characters both mythically larger-than-life and capable of eliciting empathy. She succeeds in her job: if this graphic novel is remembered by future generations, it will be for the sumptuous artwork at least as much as the scripts, even if King is presently the auteur whose name is used to sell the book.

Every last page of Supergirl: Woman of Tomorrow stands up to close inspection. Evely draws worlds that range from a pseudo-medieval fantasyland, to the interiors of a space-opera craft, and then to a vaguely Lisa Frank-ish dreamscape where sea creatures drift through a clear sky (the last of these, in a delicious piece of stylistic irony, is the backdrop to the climactic, life-and-death confrontation with Krem). No corners are cut here: the backgrounds are filled with little details, each one feeling like a world that the reader can step into and explore.

It should be stressed that, because of the heavy reliance on narration, a significant amount of the comic occurs with little or no dialogue, meaning that it is the artwork that does the heavy lifting more than anything King writes for the speech balloons. While much of the story requires the figures to do little more than to strike statuesque poses, Evely’s art also provides the requisite moments of kinetic fighting and emotive character interactions.

So, is Supergirl: The Woman of Tomorrow an artist’s comic, or a writer’s comic? Or is it one of those special cases where the two halves are balanced? This question is hard to answer. It is true that King’s densely-written narration tugs the reader away from dwelling on the artwork; yet at the same time, Evely’s fantastic worlds contain stories that are at most only hinted at in the caption boxes. The two components roll along at their own paces, each succeeding on its own terms, yet somehow always feeling separate from one another.

Supergirl: The Woman of Tomorrow appears to have been conceived to define Supergirl as a character in the same way that, say, Batman: Year One defined its protagonist. The end result seems a little too idiosyncratic to ever reach that status, but it deserves to stand as an example of how a familiar superhero can always be given a fresh new story.

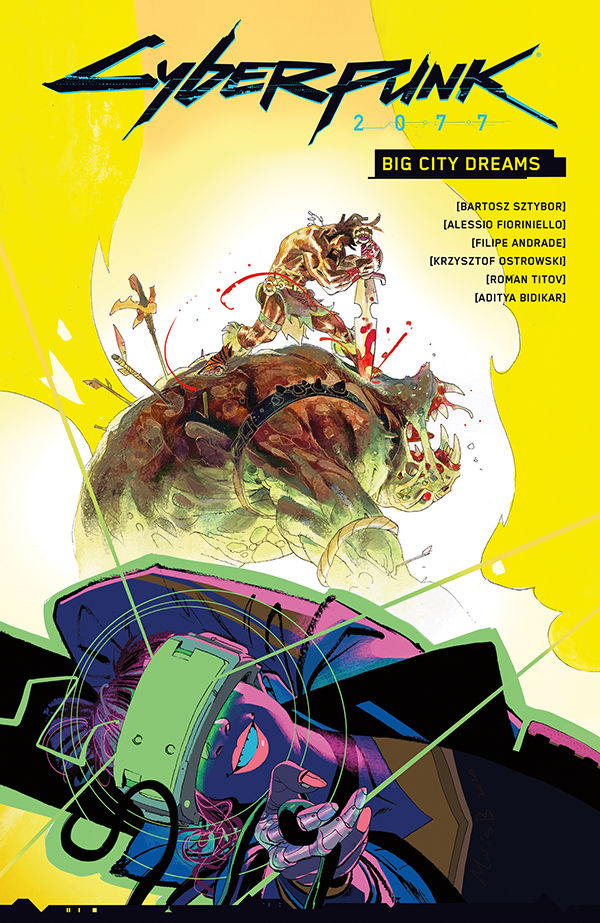

Cyberpunk 2077: Big City Dreams

So far, the Best Graphic Story category has been a string of Hugo regulars: Monstress, Saga, Once & Future and the superhero sagas of Tom King. Here, though, we enter less familiar territory with Cyberpunk 2077: Big City Dreams. This is a tie-in comic for the Cyberpunk game series, a franchise that has attracted little visible attention from Hugo voters until now.

It may have been voted onto the ballot by Chinese fans participating in the 2023 Chengdu Worldcon: note that this Hugo recommendation list posted on the Chinese social network Weixin includes the comic as one of its two picks for Best Graphic Story, the other, a Dune adaptation, also made the ballot and is discussed below.

Big City Dreams opens with a striking contrast. The first scene is set in rural America and depicts a man driving down a dusty road to his cramped house in the boondocks; were it not for the man’s robot arm and the strange, seemingly levitating devices that replace pylons, this could have taken place at just about any point in the past half-century or so. Once indoors, the man has an argument with his wife. “I can’t believe anyone in their right mind would wanna spy on our boring lives”, she says. “I know everything, Ted. I found the checks from DMS. You sold us out. Sold your life, our memories! Why?”

The action then switches to an inner-city setting. Two young drug-runners, Mirek and Tasha, drive their van through the neon-lit streets, casually committing a hit-and-run and avoiding the police by throwing the corpse of an earlier victim at an oncoming car. They arrive in time to deliver their client his dopamine-boosters, only to be screwed out of their full payment. The message of all this is that Big City Dreams may be a conventional cyberpunk story – but then again, it may not, he very ambiguity being thrown in our faces.

The aspect of the game's worldbuilding that plays the biggest role in the comic is the concept of braindances. These are advanced virtual reality simulations that can depict fantasy scenarios or real events taken directly from a person's memories -- as with the farmer seen in the prologue. Mirek, who has expressed guilt over spending time with the murderous Tasha, is an avid user of braindances. First, he tries a braindance set in a Conan-like sword and sorcery environment, but asks for something more peaceful.

“You’re an indie guy, a softy”, says the proprietor of the braindance arcade. “You dig that intellectual shit from Europe. BD’s about lonely people or about emotional cyberware, right?” Mirek declines this description, and the proprietor has him pegged for another type: “born in the badlands…or the countryside…thought he’d find a better life in Night City, escape from his drunk padre. And yet he still dreams of the cornfields stretching into eternity…”

And so, Mirek is given the braindance memories of the farmer seen earlier on in the story. He is able to escape into the lives of the couple from the time when they first moved into the house as newlyweds through to their daughter growing up and deciding to move out.

Meanwhile, Mirek is dragged still deeper into Tasha’s world of organised crime. Reluctant to live as a murderer, he returns to the arcade time and again to escape into those rural memories. The two narratives – Tasha and Mirek’s crimes, and the farming couple’s life – play out together, and between them, form an ironic fable of the proverbial grass that is always greener on the other side. While Mirel wants to flee to the country, the rural couple’s teenage daughter wants to leave her peaceful but dull surroundings and head for the city. When a noisy pair of punks drive past her family petrol-pump, she sighs: not because the peace has been shattered, but because the motorists are living the life that she herself dreams of.

Cyberpunk 2077: Big City Dreams is a slim book with only fifty pages of story; the plot could conceivably have been squeezed into a single 24-page standard US comic issue, although it would have had much less space to breathe. That additional room turns out to be vital, as the comic is more about atmosphere than incident.

The Cyberpunk 2077 game on which it was based was developed by Polish company CD Projekt Red, and Big City Dreams is likewise a European creation, with a mixture of Polish, Italian, Portuguese and Russian talent (plus India-based letterer Agitya Bidikar). The dialogue quoted earlier regarding “intellectual shit from Europe. BD’s about lonely people” is perhaps a sly acknowledgement of the comic’s origins. BD stands for braindance – but it can also stand for bande dessinée, the French term for comic book.

The artwork by Alessio Fioriniello and Filipe Andrade shows an intriguing blend of influences, a European flair mixing with Katsuhiro Otomo-esque subject matter to create a world of expressive, stretchy-faced characters. A clever visual irony is that, of the two main settings, it is the small-scale rural home that is given more detail. The care that has gone into drawing every wooden panel in the little shack and every crop in the field is palpable, while the city itself is blocked in with deliberately bland and generic buildings. The urban backdrops are so interchangeable that, in many cases, it falls upon colourists Krzysztof Ostrowski and Roman Titov to distinguish one area from another. All of this helps to drive home Mirek’s desire to leave for the country.

The five-page sword-and-sorcery sequence (which, despite its brevity, is spotlighted on the book’s cover) is also handled well, with the team leaning into Moebius-style fantasy illustration. Big City Dreams fulfills the old showbusiness rule of leaving the audience wanting more: it is easy to imagine this team telling similarly accomplished stories in a wide variety of different settings.

Is Cyberpunk 2077: Big City Dreams really the sort of standout work that deserves a place on an award ballot? Well, probably not, and people looking back on the 2023 Hugos in years to come might wonder why it was deemed significant at the time. Yet it remains a solid and concise piece of graphic storytelling that can be appreciated even by readers who have never played Cyberpunk 2077.

Dune: The Official Movie Graphic Novel

The final contender for Best Graphic Story is another comic that was included on the aforementioned Weixin recommendation list, and it’s an adaptation from Legendary Comics of the well-received 2021 Dune film, itself based on Frank Herbert’s classic 1968 science fiction novel.

Just as the 2021 movie was not the first film version of Herbert’s book, this graphic novel is not the first Dune comic. A psychedelically-influenced version, written by Ralph Macchio, drawn by Bill Sienkiewicz and based on the 1984 David Lynch film, was published by Marvel in the 1980s. More recently, Boom! Studios released Dune: House Atreides, adapted from Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson’s prequel novel.

And now, we have a comic-of-the-film-of-the-book to take us on another trip to a future in which interstellar travel coexists with a feudal social structure, and where the young aristocrat Paul Atreides faces up to his key role in the affairs of his hostile planet – a role shown to him by prophetic dreams.

Three writers – Denis Villeneuve, Eric Roth and John Spaihts – are listed as adapting the screenplay into comic form, with Lilah Sturges credited as the comic’s scriptwriter. The end result is very close to the film in content, omitting a few of the less important stretches of dialogue but retaining the bulk of the story.

As for the artwork by illustrator Drew Johnson and colourist Zid Niezam, how closely this follows the film varies from sequence to sequence. Some stretches of the comic, such as the first scene in which Paul speaks to his father, are modelled directly upon stills from the scene: even the individual curls of Timothée Chalamet’s hair are captured with fidelity. In other scenes, such as the earlier sequence in which Paul has breakfast with his mother, Johnson shows more imagination in how he transfers the plot to the page, coming up with his own compositions while maintaining recognisable likenesses of the film’s actors.

While many would dismiss a comic where about half of the panels appear to have been traced from film stills, we should not overlook the creative thought that must have gone into even the most literally-translated sequences. Johnson and, presumably, writer Sturges will have had to consider which shots to adapt, how large each panel should be, how much space should be given to each scene and how best to capture the rhythm of the film.

By way of illustration, consider the film’s portrayal of the “gom jabbar” test, in which Paul is forced to place his hand into a box and experience excruciating pain. His is not something that can be translated directly to comic format. It relies upon the performance of the actors and the passage of time to emphasise how long his ordeal is taking. The comic’s adaptation seems one of the more “traced over” sequences in the book, yet it remains a well-crafted piece of sequential storytelling. The balance between long shots and close-ups, the choice of expressive character shots and even the additional light on the protagonists’ faces all succeed in generating tension and mood, conveying the feel of the film’s sequence within a completely different medium.

Admittedly, a few aspects of the film are lost in translation. One sequence in the movie shows Paul fencing with a second character, their weapons producing a holographic flicker on impact: the flicker is ordinarily blue, but if the blow is one that would have been fatal with a real weapon, it becomes red. When viewed in motion, this makes perfect sense; but when translated directly to the comic page, the flicker becomes a mere haze. The meaning is lost, and a reader unfamiliar with the film might take the red haze as indicating acual blood. This is a case where the comic would have been better off coming up with its own visual language, rather than drawing straight from the film. On the whole, however, the awkward moments are outnumbered by smoother translations.

So, the comic serves its main purpose of turning the film into a series of pages and panels. Its presence on the Hugo ballot, meanwhile, still leaves us with one significant question: is it really award-worthy? Had the creative team embarked upon a direct adaptation of the novel, translating Herbert’s fictional world using their own terms, and ended up with a similarly solid result then this would be an impressive achievement. But the fact remains that, as they were working from a film adaptation, a significant chunk of the job (arguably the majority of it) had been done for them.

Comic adaptations of films had their heyday in the years before home video became commonplace and films were harder to revisit. After this, they became easiest to justify when the artists involved were able to put a unique flair on the page (see, for example, Mike Mignola’s idiosyncratic work in adapting Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula). Dune: The Official Movie Graphic Novel, while handsomely-mounted, never manages to breathe new life into its source material. An award-winner is, ideally, something that stands the test of time; but of all the Dune adaptations in existence, this is the one most likely to be forgotten.