2021 Hugo Award for Best Graphic Story Part 2 (Patreon)

Content

By Doris V. Sutherland

As an exclusive for our Patreon subscribers, here is the concluding part to Women Write About Comics’ examination of the 2021 Hugo Award for Best Graphic Story finalists…

Once & Future Volume 1: The King is Undead

Duncan McGuire’s date is interrupted by a phone call telling him that his grandmother has wandered out of her care home. When he tracks her down, the elderly-but-robust lady reveals a cache full of heavy-duty firearms and a life full of big secrets. It turns out that Gran has a history as a monster-hunter, and Duncan soon encounters his first monster in the form of a snake-headed, mammal-bodied Questing Beast.

As Gran explains, the appearance of the Questing Beast is just one sign of something more serious afoot: an archaeological dig has discovered the scabbard of Excalibur, and a far-right extremist group has stolen this enchanted artifact for use in a plan with grave implications.

“Never trust a prophecy that can be taken in two ways” says Gran, commenting on the legend of King Arthur’s return during Britain’s darkest hour. “Well, he could return because it’s Britain’s darkest hour, sure… or his return could cause it.”

When Arthur is resurrected, it is as a skull-faced undead monster with a taste for human blood and little love for the nationalists who summoned him (after all, they are Anglo-Saxons, the invaders he once fought against). But the political extremists were merely pawns in a larger plan – a plan to resurrect not only Arthur but the stories connected to him, with potentially apocalyptic consequences.

Once & Future is one of two books written by Kieron Gillen to be up for the Hugos’ Graphic Story award this year, the other being the second volume of Die. The two comics each make an intertextual engagement with the fantasy canon: Die depicts a role-playing game come to life in which historical authors (J.R.R. Tolkien, Charlotte Brontë) appear as doppelgangers; Once & Future tackles Arthurian legend in a similarly playful manner.

But the two comics also have a significant difference in storytelling style. Die is dense, richly-layered, and difficult to summarise to any satisfaction. Once & Future, on the other hand, can be neatly summed up in a single line: this is an action-horror comic with guns, swords and a zombie King Arthur.

That said, Gillen’s metafictional interests are still on display. A major aspect of the comic’s worldbuilding is the notion of story as a tangible, even lethal force. “Yes, the world is haunted”, says Gran. “Haunted by these feral stories. They lure us in, they’d gobble us up, given half a chance… takes a certain sort to go wandering in the woods. Looking for wolves.” King Arthur is clearly famed as a character from a story; his emergence into the real world opens the door for other elements of his story to come through – leading to the creation of a new Galahad, a new Fisher King and so forth. The comic’s doomsday scenario is for the story to be retold in its entirety, thereby replacing reality altogether.

Arthur’s status as a character in a story raises the question of exactly which story this undead Arthur came from, in turn allowing Gillen to show off his research. When the heroes see Arthur draw a sword from a stone, Duncan assumes this to be Excalibur; his Gran points out that, in most stories, Excalibur belonged to the Lady of the Lake. She theorises that it might actually be another legendary sword, Clarent, only to reconsider: “That’s probably too late. 14-15th century. This Arthur seems mainly early Welsh. Mainly.”

Still, compared to Die, where the interaction with earlier works of fantasy was the entire point, this is fairly basic. The intertextual aspect of Once and Future is an elaborate layer of icing, the base of the cake being the sword, sorcery and shotgun romp. And a tasty cake it is: the two main characters – the clumsy but athletic academic and his gun-toting badass grandmother – make an engaging double act, and the surrounding story does them justice.

Dan Mora’s artwork is a world away from Stephanie Hans’ paintings on Die, yet perfectly suited to the story Gillen is telling here. The comic’s protagonists are an expressive set of caricatures, while the undead villains are well-rendered and would have been right at home in a fifties EC comic. Most notable of all is the sheer dynamism that Mora brings to the story, with quite literally every panel filled with either kinetic energy or smouldering tension. This fits Gillen’s script, the pace of which likewise never lets up. Once and Future is not a story where the characters get to sit down and catch their breath: even the dinner-date scene that introduces Duncan takes place immediately after he has spilt wine over his girlfriend’s front.

Tamra Bonvillain’s colouring adds still another layer to the most appetising cake. Although defaulting to earth tones, the comic’s palette changes abruptly when the supernatural phenomena flares up, with lime and magenta glowing from between the inky pools of shadow. Somehow, this colour scheme is able to evoke the more lurid areas of fantasy iconography – namely vintage RPG box covers and 8-bit video game graphics – without lowering the overall tone of the mytho-horror.

While most of the comics in this year’s Hugo ballot (even Ghost-Spider Volume 1) are continuations, Once and Future Volume One is the start of its story. A second volume is already available, but the first book works well as a stand-alone piece.

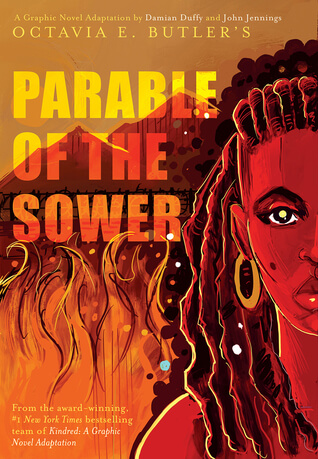

The Parable of the Sower

Lauren Oya Olamina is a teenage girl who lives in a dystopian California. Her neighbourhood is surrounded by a wall to protect it from the crime and violence that exists throughout the rest of the town; but life is grim even on the inside of the wall. The older generation – including Lauren’s father, a Baptist preacher – find solace in religion: “To the adults, going outside to a real church was like stepping back into the good old days when there were churches all over and too many lights and gasoline was for fueling vehicles instead of torching things.”

The younger generation has little faith in spiritual matters, however. Some, like Lauren’s brother Keith, aspire to reach Los Angeles and fulfill vaguely-defined dreams of material benefit, despite being assured by adults that the big city is simply more of the vice and poverty that stretches far beyond the wall. Lauren, however, has her mind on higher matters. Rejecting the religion of her father, she begins developing her own spiritual philosophy. Dubbed Earthseed, Lauren’s pointedly anti-traditional religion holds that change itself is divine; that adaptability, persistence and positivity are essential; and that humanity’s future lies not in walled neighbourhoods, but amongst the stars.

Parable of the Sower is an adaptation of the 1993 novel of the same name by Octavia Butler. Writer Damian Duffy and artist John Jennings, who previously adapted Butler’s novel Kindred, had the job of translating her dystopian classic into graphic format – and an intimidating task it must surely have been.

In Butler’s original novel, much of the story is conveyed through Lauren’s internal thoughts, from her memories of all that she has witnessed to her blossoming spiritual theories. John Jennings captures this subjective aspect through a self-consciously handmade aesthetic. The motif of lined notepad paper crops up repeatedly, being used as the background to Lauren’s narrative captions and, indeed, even the background to the whole of the page that first introduces Lauren as a character, after which it blurs into the barbed wire fence atop the neighbourhood’s wall. The characters and their settings are digitally-painted in a brash, blocky manner that suggests markers or wax pastels, almost as though the entire saga is being told through an elaborate series of payment murals.

An obvious hurdle faced by any attempt to adapt Parable of the Sower visually is the sheer brutality of the society depicted in the novel. The city inhabited by Lauren is one in which men, women and children alike are routinely subjected to murder, mutilation, slavery and rape. In the novel this is detailed by Lauren’s narration in an understated, even detached manner that allows full emotional impact without ever becoming sensationalistic or exploitative. The comic shows a considerable degree of inventiveness in translating this into illustrations.

The moments of graphic violence are carefully-placed and so heavily stylised that they come across more as Lauren’s impressions of the atrocities – a technique that, in its way, lends the scenes more impact than point-blank literalism would have done. Elsewhere, death is portrayed simply through a chilling absence: early on we meet a minor character, a little girl whose blonde hair and a white-toothed smile stand out sharply from the comic’s muted colour scheme. Her death is described rather than shown, yet her passing is signalled by yellow and white vanishing from the palette.

Like any good adaptation, the comic is able to tease out the hints and implications of its source while leaving a fair number of blanks to be filled. In the novel, one character’s death is revealed in a single-line diary entry in which Lauren gives a flat description of her parents being called downtown to identify the body. The comic adapts this into a two-panel sequence in which we not only see Lauren writing the line in question, but throwing the diary at the wall in anguish. In each case, the story demonstrates exactly how to land an emotional punch in a confined space: the medium is different, the effect is the same.

The novel later provides a graphic description of the flayed, burnt corpse; the comic avoids depicting this, instead putting the description into the mouth of Lauren’s father. While we do not see the brutality itself, we see its aftermath: the solemn father, the shocked and tearful faces of those listening to him, and the overall ambivalence of Lauren – whose relationship with the deceased was far from positive.

One aspect of Butler’s story that allows the comic adaptation to come into its own is Lauren’s hyperempathy. As a result of her mother having abused a drug when pregnant, Lauren has a condition (officially known as “organic delusional syndrome”) that causes her to share the physical pain of those around her. The comic is able to depict this in visual terms, with expressionistic sequences in which various impacts and injuries are projected onto Lauren’s body.

The more cerebral aspects of the novel – namely, Lauren’s philosophical development – pose a bigger problem for a comic adaptation. Damian Duffy makes a valiant effort to covey the protagonist’s

internal state, filling a few choice pages with Lauren’s notepad musings and even reviving that much-despised comic convention of the thought balloon; nonetheless, a good deal of Butler’s writing has been sacrificed. For example, consider this excerpt from Lauren’s narration in the novel:

A lot of people seem to believe in a big-daddy-God or a big-cop-God or a big-king-God. They believe in a kind of super-person. A few believe God is another word for nature. And nature turns out to mean just about anything they happen not to understand or feel in control of.Some say God is a spirit, a force, an ultimate reality. Ask seven people what all of that means and you’ll get seven different answers. So what is God? Just another name for whatever makes you feel special and protected?

After spending a long paragraph pondering the role of God in a storm that killed more than 700 people in the Gulf of Mexico, Lauren delves still deeper into theology:

Is there a God? If there is, does he (she? it?) care about us? Deists like Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson believed God was something that made us, then left us on our own.“Misguided,” Dad said when I asked him about Deists. “They should have had more faith in what their Bibles told them.”I wonder if the people on the Gulf Coast still have faith. People have had faith through horrible disasters before. I read a lot about that kind of thing. I read a lot period. My favorite book of the Bible is Job. I think it says more about my father’s God in particular and gods in general than anything else I’ve ever read.

The comic compresses all of this into a few narrative captions across a single page:

A lot of people seem to believe in a big-daddy-cop-king-God. A super-person. Others think God is a spirit, a force. Or another word for nature. There’s an early-season storm blowing through the Gulf of Mexico. More than 700 known dead so far. Mostly the street poor. That’s nature. Is it God? Is it a sin against God to be poor? My favorite statement on my Father’s God—and on Gods in general—is the Book of Job.

But while the comic may sometimes sacrifice the intellectual for the visceral, this is easy to forgive when we consider just how adeptly it meshes the visceral with the artful. Jennings’ artwork uses a range of expressionistic techniques to capture the emotional states of its characters: the anguish, the sorrow and the occasional moment of precious joy that are shared by Lauren and the rest serve to warp and transform the barren landscape that surrounds them.

Of course, discussing Parable of the Sower in formalistic terms risks losing sight of the story being told. A rich story it is, too, filled with the anger, anxiety and hope of a young character forced by the world to become wise beyond her years. Lauren suffers one loss after another until, finally, she is driven to flee her neighbourhood altogether. While travelling with a band of fellow refugees, she keeps much of herself hidden, even disguising herself as a man. Over time, however, she opens up to her travelling companions about such personal topics as her hyperempathy and her spiritual theories. The band must take harsh measures to protect their resources; and for Lauren, one of the most valuable resources of all is her faith.

We live at a time in which dystopian fiction has been heavily commoditized, with totalitarian regimes being popped out as though by an assembly line, each ready to be toppled by a plucky teenage protagonist. Parable of the Sower turns its face against such easy reassurances, however.

“Cities controlled by corporations are old hat in science fiction” says Lauren at one point, as she reads one of the SF novels left by her grandmother. “The company-city subgenre seems to star a hero who beats ‘the company.’ I’ve never read a novel in which the hero fights like hell to get taken in and underpaid by the company. In real life, that’s how it is.” As it happens, Lauren follows neither path: she ploughs her own furrow, one that takes her away from the cities – indeed, Earth itself – altogether.

This mirrors Octavia Butler’s own working method. While the SF canon afforded many easily-imitable dystopian novels, she wrote a deeply personal work that incorporated contemporary social issues and African-American history (one plot point even hinges on Laurens’ grandfather having chosen a Yoruba rather than Swahili family name in the sixties). The comic adaptation never obscures or dilutes this, and instead demonstrates the continued resonance of the original novel.

Much has been made in recent years of Butler’s prescience: Parable of the Talents, the 1998 sequel to Parable of the Sower, has a presidential candidate running on a platform to “make America great again”. Many adaptors would be tempted to bridge the gap and insert commentary on events from after the novel was written; Duffy and Jennings, however, generally avoid this.

Granted, the twenty-first century is not completely absent from this nineties-conceived dystopia. When the characters reach a station supplying water (a valuable and highly-commercialised commodity in this drought-stricken future) a sign declares it to be “sponsored by Notslē” – an obvious dig at Nestlé, whose bottled water operations are an ongoing source of controversy. This scene, however, is an exception to the general rule.

The story is still set during the 2020s, even though this is no longer the futuristic decade that it was when Butler was writing. There is no attempt to shoehorn in a Donald Trump-like character as foreshadowing of the newly-relevant sequel, nor has the technology level been updated: astronauts have landed on Mars, but mobile phones are conspicuously absent. By and large, this is a comic that could conceivably have been published in 1993, the same year as the original novel. The fact that it still carries so much weight is a testimony to both Butler and her adapters.

Octavia Butler wrote a dense, challenging and rewarding novel. Damian Duffy and John Jennings have successfully adapted it into a dense, challenging and rewarding comic. Any material that is lost in translation receives more than adequate compensation in the rich new dimension provided by Jennings’ artwork, which brings Butler’s world into starkly expressionistic territory. The comic version of Parable of the Sower does full justice to its well-regarded source text – and, perhaps, will help bring a new generation of admirers to the work of Octavia Butler.

Monstress Volume 5: Warchild

Created by writer Marjorie Liu and artist Sana Takeda, Monstress has been a fixture of the Hugos’ Graphic Story category for years now. The series won the award every year from 2017 to 2019, and even in 2020 it was a runner-up. Now, the fifth volume has become the latest instalment of this bloody and beautiful saga to be in the running for the award.

Monstress Volume 5: Warchild is set during a war between the human Federation and the Arcanics, a diverse species of various human-animal hybrids. The cause of the conflict was a bomb attack on a human city; although the bombing was carried out by a splinter group of the Arcanics, the human military nonetheless views the latter race as demons to be vanquished.

The central character in the story is Maika Halfwolf, a shaman-princess who shares her body with an eldritch entity named Zinn. This being lends her a Jekyll-and-Hyde aspect, although recent events have caused her two halves to blur together somewhat: her remorse at being forced to drain the lives of others vampire-fashion as a means of survival has begun to fade, and she recognises the usefulness of Zinn to her role as military leader.

Maika tackles the psychological side of warfare with a flare that would have made Vlad the Impaler proud. After her first encounter with Federation soldiers, Maika sends two surviving back to their camp wrapped in barbed wire, their lips sewn up, and the severed heads and limbs of their dead comrades tied to their bodies. “In war, no one wants a friend”, says Maika when justifying her ruthlessness. “They only want killers who will help them survive.”

Each issue in the volume opens with a brief flashback sequence depicting an earlier battle between humans and Arcanics, during which Maika served as a child-soldier. The young Maika is portrayed as something of an ingénue, her similarly-aged comrade Tuya taking on the role of unsentimental pragmatist that Maika herself would later adopt. Taken together, the sequences fill in a chunk of Maika’s backstory – right up until she is possessed by Zinn – and at the same time underline just how young she is in the present-day portion of the story: only six years have passed since Maika was the tiny child of the flashbacks.

Maika’s hard-headedness puts her into conflict with the secondary protagonist, a small fox-girl named Kippa. Clinging to an intense faith in the sanctity of a promise, Kippa insists on fulfilling a vow by helping the fox-people currently sheltering in the city of Ravenna – which is due to be attacked by the Federation – in violation of Maika’s wishes. Although hardly unaware of life’s cruelty (she lost her entire family) Kippa embodies the idealism and compassion that Maika has forced herself to shed; the Halfwolf’s treatment of the fox-girl alternates between warmth and coldness, but the fact that she keeps Kippa around at all indicates that she is not as harsh as she might seem on the outside.

While Kippa is an easier character to sympathise with than Maika, she is also wrong – catastrophically so. Her good heart and idealism result in a deadly attack on the city. Monstress is not only brutal, it is also brutally honest, and does not shirk from following the details of its conflict to their harsh conclusions Yet even so, it never loses its touch of warmth, or allows hope to be completely quashed. We see this again in the character of Kippa, who strives to make amends for her grievous error: the voice of principled and hard-won optimism to the end.

Sana Takeda’s artwork gives full representation to the contradictions and ironies implicit in Marjorie Liu’s script. The world of Momstress is one of statuesque beauties in ornate art nouveau uniforms; majestic tiger-faced men and enigmatic seahorse-headed people; taking cats with many tails and warriors riding into battle atop unicorns. But it is also a world of firearms, bombs, tanks and explosion-sundered bodies scattered across a battlefield amidst a murky, all-pervasive fog. Even amidst these grim echoes of real-life twentieth-century warfare, however, we find fresh shoots of sweetness – represented (once again) by Kippa, a cartoon cherub straight out of a Studio Ghibli film.

The comic roughly divides the fantastic and the mundane across the lines in the conflict, with magic and animal-people on the side of the Arcanics while the humans are given tanks, walky-talkies and dour sepia fatigues. Leading the latter force is Colonel Anuwat, a white-haired, scar-faced woman who has all of Maika’s ruthlessness but none of her mythic romanticism. Were it not for her gender, she could easily have turned up in a Vietnam War film as a cold-blooded commanding officer. The human army has its weird aspect as well, however, as embodied by a group of deadly nuns: white-skinned, Goth-like warriors with supernatural abilities.

All of this is merely one instalment in an ongoing narrative. Indeed, the bombing attack that initiates the conflict is simply an attempt to unearth a buried fragment of a mask, effectively rendering the entire conflict collateral damage in an artifact-hunt. The final issue in the collection sees a confrontation between Maika Halfwolf and Colonel Anuwat, which in turn paves the way for more exploits and intrigue. Anybody who has followed the series this far will need little encouragement to pick up the next volume: Monstress Volume 5 is just further confirmation that the series is something special.