Supper Mario Broth: The Lost Levels, Issue 6, Week 41/2018 (Patreon)

Content

Welcome, Supper Players, Broth Siblings and Supperstars, to the sixth issue of the Supper Mario Broth: The Lost Levels feature! Thank you so much for your continued support into the second month of the operation of the Patreon! Unfortunately, October has been very stressful for me in terms of personal issues so far, which means that this is the second time in a row that the column was delayed. I understand if you feel like you are not getting the value you are paying for as I am not fulfilling the deadlines; you may request a refund by contacting me over Patreon and I will issue it immediately. Before I start, let me briefly restate some things of note about the article series. For more detailed explanations, please refer to Issue 1.

- All images without an attribution have been recorded/created by me. If you wish to know what emulators/programs I used, please leave a comment. I will reply promptly.

- All comments and criticism are greatly appreciated, and all suggestions are evaluated and incorporated into future issues. You can shape the form and content of the articles with your feedback, so don't hesitate to tell me anything!

Now, let us look skyward and welcome a new galaxy of obscure Mario content.

This is Supper Mario Broth: The Lost Levels.

Which Game has the Fastest Mario Speed?

Despite not resembling what one may imagine an athletic person to look like, Mario can run very quickly in some of his games. So quickly, in fact, that Super Mario Bros. was the inspiration for Sonic the Hedgehog, a game series defined by having a main character who is extremely fast. This, of course, brings up an intriguing thought: when has Mario been the fastest?

There are several issues we must tackle before even starting to measure Mario's speed. First, we must think of what speed is, according to physics: distance traveled, divided by time to travel, or colloquially, "distance over time". In the case of Mario games, we have difficulty measuring both distance and time, for different reasons. Let us start with distance.

As convenient as it would be for Mario games to provide measurements for objects featured in them, and as admirable as it would be for Nintendo to keep the measurements consistent between all games, we are getting neither of these things. Countless fans have made their own theories about Mario's height, about the size of his world, and about the strange relationship between the shifting sizes of different characters in the Mario franchise - and none of those theories are more true than any other, as even in the few cases where an object in a game can be used as a reliable yardstick, the measurements become inconsistent the second it is applied to any objects outside the game it is in. Therefore, while we may hypothesize Mario's size in some narrow context with a degree of certainty, to do so for the entire franchise seems to be impossible.

Therefore, I will not use "absolute" distance in my calculations. Instead, I will measure Mario's distance relative to his own height - a distance not in feet or meters, but Marios. This sidesteps the entire problem, but of course delivers a much less useful result, as we can never know by how much Mario has shrunk or grown between games - if he is supposed to shrink or grow at all, but it is clear something - Mario or the environment - changes size between games all the time. Still, it may be of interest to see what game Mario has the highest speed relative to his height in.

Of course, for games with both Small Mario and Super Mario, we must decide what height to use. As starting with New Super Mario Bros., Super Mario has been depicted as the regular Mario 3D model while Small Mario has drastically different proportions, we can say with confidence that Super Mario is what Nintendo currently considers Mario's "regular" size to be. As such, we will use Super Mario as the "one Mario height" unit for games where he is present.

A different problem presents itself in the matter of measuring time. At first, you would think that there should be no issues, after all, can we not just measure seconds? There is a theoretical obstacle and a practical one. First off, not all Mario games run at the same number of frames per second. In some games, Mario "moves" 60 times during one second of observer time, while in others, it is 50 or 30. The practical one is rather embarrassing for me, as it would be no problem for someone with better equipment: I can simply not emulate certain games at the correct speed, as my computer is not powerful enough to do so. If I were to measure the speed in seconds, it would be slightly off for older games, and wildly off for newer games. Therefore, I must make a concession and measure Mario's time in frames rather than seconds.

So, to recap, we are measuring Mario's/Super Mario's distance measured in his own height traveled over time measured in frames. While it is not as exciting as knowing his speed in miles per hour, "Marios per frame" still gives us a vague idea of which games he is faster and slower in.

A final note: I am going to measure Mario's running/dashing speed in some of what are considered "mainline Mario platformer titles". While Mario has methods of moving faster than running in many of them, measuring them is much more difficult and not really comparable. In contrast, Mario can run or dash in all of these titles, giving us a more or less consistent framework. And while it would be great to compare every single Mario game where Mario can move around, to do so is simply impossible for me, as I cannot emulate them all, and footage recorded and uploaded to Youtube is often frame-inaccurate.

Let us start with Super Mario Bros. for the NES. I let Super Mario dash at maximum speed for 50 frames; left is Frame 1, right is Frame 51.

Super Mario's standing height is 32 pixels - if you attempt to measure it yourself, you may come up with 31 pixels - but this is because if you look closely, Mario's feet overlap the ground by one pixel. The concept of one-pixel ground overlap in Mario games is a topic I will tackle in a future article. In 50 frames, he travels 121 pixels. This makes his speed 2.42 pixels per frame, or 0.076 Marios per frame. Of course, due to games using subpixel values, many Mario games will have Mario move very slightly different distances each frame, which is why I use an average value.

An interesting thing to note about the measurement in frames is that it is relevant for the very first game we analyze, as the European version of Super Mario Bros. runs at a different framerate and is in fact 20% faster when played with the usual 60 FPS. If we counted the seconds, European Mario would be much quicker than American or Japanese Mario, even though clearly within the context of the game, he moves at the same pixel/frame speed.

Next up, Super Mario Bros. 2, but before that, a quick note about the original Super Mario Bros. 2, known internationally as Super Mario Bros.: The Lost Levels. Mario moves at the same speed in that game as in the original Super Mario Bros.

Mario's height in this game is 27 pixels, and he travels 113 pixels in 50 frames. Thus, his speed is 0.084 Marios per frame. While the "feeling" of his movement is much slower than Super Mario Bros., as he travels a lesser distance across the screen, the fact that he is shorter makes him actually faster from an in-universe point of view.

Super Mario Bros. 3 introduces the P-Meter, which allows Mario to dash much faster after not being interrupted for a set amount of time. Even though the P-Meter dash is different from the normal dash used by Mario prior, it is still a form of running and will thus be counted.

Mario's height in Super Mario Bros. 3 is again 27 pixels, and the distance he travels in 50 frames in 176 pixels, much greater than the previous games. Thus, his speed is 0.13 Marios per frame, almost twice the speed of Super Mario Bros.

In Super Mario Land, Super Mario's height is 16, which is normally the height of Small Mario, and he travels 56 pixels in 50 frames, resulting in a speed of exactly 0.07 Marios per frame, the slowest result yet.

But this is not nearly as slow as Super Mario Land 2 Super Mario, who is again 27 pixels tall but moves only 74 pixels in 50 frames for a record low speed of 0.055 Marios per frame.

In Super Mario World, Super Mario is very slightly taller than usual at 28 pixels, and moves 150 pixels in 50 frames, resulting in a speed of 0.11 Marios per frame, faster than any other game except Super Mario Bros. 3 in the pre-Nintendo DS 2D Mario platformer lineup.

I will finish the 2D platformers by looking at New Super Mario Bros. While there are undoubtedly differences between it and the three later sequels, from my experience Mario should move at about the same speed within them; in addition, I cannot emulate the others.

In New Super Mario Bros., Mario is roughly 31 pixels tall. I say "roughly" because due to the introduction of idle animation, there is no definitive "standing" sprite for Mario to go off of, as he keeps swaying slightly at all times. The number 31 is my personal estimate for Mario's average height, and is not as accurate as previous games.

Mario travels (again, roughly) 155 pixels in 50 frames, putting his speed at ca. 0.1 Marios per frame, slightly slower than Super Mario World.

This marks the point where results with any kind of credibility stop. I will post a comparative list of speeds, but before that, let us take one final entirely non-rigorous look at Super Mario 64.

Mario is more compact in this game, which means he runs relatively quickly compared to his height. I have determined the speed to be 0.39 Marios per frame using the pattern on the wall as a reference; even if it is wildly inaccurate, it blows all previous speeds out of the water.

However, we will not include this in the final list of speeds - at least for now. I intend to research tools that will let me measure distances in 3D Mario games more accurately, and at a later date, revisit this topic to add those speeds; but right now, here are the comparative speeds of Super Mario in 2D mainline Mario platformers:

Super Mario Bros. 3 - 0.13 Marios per frame

Super Mario World - 0.11 Marios per frame

New Super Mario Bros. - ca. 0.1 Marios per frame

Super Mario Bros. 2 - 0.084 Marios per frame

Super Mario Bros. - 0.076 Marios per frame

Super Mario Land - 0.07 Marios per frame

Super Mario Land 2 - 0.055 Marios per frame

As we can see, the Game Boy games are the slowest, most likely due to needing to restrain Mario's speed so he does not run too fast for the small screen to be able to adequately warn players of oncoming danger. Super Mario Bros. Mario may be fast in terms of his speed relative to in-game tiles, but his taller height makes him the slowest home console 2D Mario in terms of Marios per frame. Finally, the P-Meter makes Super Mario Bros. 3 Mario undoubtedly the fastest of them all. In fact, he is so fast time actually slows down when he is running at full speed.

In the future, we will continue this comparison by looking at 3D games.

The Progressive Paperization of the Paper Mario Series

Have you ever felt that the latest entries in the Paper Mario series have had a very large focus on paper? More than simply having the entire game world and all characters within it made of paper, now paper is being constantly referenced in dialogue, many interactions with the world are based on actions commonly performed on paper (cutting, ripping, folding etc.) and even the aesthetics of the heads-up display, menus and other interface elements have become entirely paper-themed.

I will now examine how the series, despite containing the word "paper" in the title from the beginning, in reality did not do a lot with the concept, but then became increasingly aware of it and finally grew into a franchise that attempts to reference paper in every way possible, as it does now.

First, let me point out that the last sentence is not entirely correct. In fact, Paper Mario does not contain "paper" in the title, at least not in Japan.

Instead, it is called "Mario Story". Since the Japanese version released first, it is actually accurate to say that the series started by not referring to paper in its title. Of course, the title is not as important as the content, and clearly Mario - and everyone else here - is made out of paper... or are they really?

If you have seen the US commercial for the game, you may have been primed to believe that the game clearly states that all of its characters are made out of paper. However, this is not the case. I have analyzed the entirety of the text in the code of Paper Mario and the only occurrence of the word "paper" referring to a character (outside of two tongue-in-cheek references to the name of the game itself) is this:

"Mario, you're really good at climbing down that pipe! You roll up like paper and spin on down! That's so cool!"

This is said by Goombario about Mario going down a pipe to the Toad Town Tunnels. Note that Goombario says "like paper". Even though he acknowledges the paper-like quality of Mario's movement, he does not imply that Mario is literally made out of it.

While the aesthetics of the game are very paper-like in how angular and simplistic some of the environments look, there is no "exposed behind-the-scenes arts and crafts" theme that has become popular in later games in the series. While rocks may look like paper maché, the outer layer never peels off to reveal newspapers underneath. While the rooms look like dioramas, the floor does not show corrugated cardboard through the cracks, and so on. Some visual effects treat the world like paper, such as building walls folding to show what is inside, but the actual objects are not shown to be actual paper, but merely two-dimensional.

The only exception is the battle screen, where some of the scenery is very heavily implied to actually be paper, such as this cloud:

However, this may be due to the battle screen being a stage, and the paper objects could represent cheap props. None of these obviously paper items appear outside of battle.

I realize there is a thin line between "paper-like" and "actual paper", and the argument can be made that the lack of distinct "tells" that the world is an arts and crafts project is due to the limitations of the hardware. Thus, this is not a strong argument and I would say the lack of direct references to paper in the text is the main point in favor of Paper Mario being not too heavily paper-themed.

Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door marks the point where the series also receives a "paper" title in Japan (listen for the title at 12 seconds in). Let's look at the text again first. In addition to the ever-present references to the game title (and another reference to "Paper Luigi", a game yet to be released), Mario is finally referred to as paper:

The Black Chests contain entities that "curse" Mario with powers allowing him to harness his paper-like nature and become different paper constructs, like a plane, a boat, or a tube.

One of the powers is just called "Paper Mode", but curiously, in-game all characters refer to using Paper Mode as becoming "paper-like" or "paper-thin". The plane and boat, however, are explicitly referred to as paper.

On the aesthetic front, the game references paper much more extensively than Paper Mario.

Screen transitions now employ an effect that scrunches up the screen like paper.

Whenever an event causes a change in the environment, a variety of paper-inspired visual effects are used to present it, such as this flipbook-type reveal of a bridge in Chapter 1. The environment gets ripped, folded, and unfolded in a way that does not merely exploit its 2D nature, but uses paper textures and sounds.

Finally, during some sections, Mario is able to stand on 2D structures in the background of some areas, which was not possible in Paper Mario. In fact, this one feature has been increased in importance to the point of being the focus of the next game in the series: Super Paper Mario.

Interestingly, Super Paper Mario never refers to any characters as being made out of paper, and in fact dials back on all paper aspects by employing drawing effects instead of paper-themed effects for environmental changes. Instead, a different gimmick is played up: that of characters being aware that they are two-dimensional.

This has not been referred to much in the previous two games, but in Super Paper Mario, it is practically the main plot point.

Mario is gifted the ability to flip between dimensions, which for the Super Paper Mario universe, is special; meaning that most entities within it exist in 2D only. (Although a surprising amount of characters who should logically not have this exclusive ability still do, leading to descriptions like "It's a Goomba, one of Bowser's minions... It really puts the "under" back in "underlings"... It has no remarkable traits... Well, except this one has the ability to flip between dimensions...")

So while the paper aspect is dialed back, the in-universe view of characters as flat is enforced much more than in previous entries in the series. This all comes together in full force in Paper Mario: Sticker Star.

This is an example of dialogue near the beginning of the game. As you can see, the characters are now, for the first time, aware of the fact that they are made of paper, and are embracing it completely. Also note that the Toad said he was "raised" to keep his creases crisp, meaning that in-universe, everyone has been made of paper for at least a very long time, but presumably forever.

This, of course, does not seem to make sense given how the previous games were presented as stories that happen within Mario's normal world, but merely stylized. One strong case that connected the previous Paper Mario games' world with the regular Mario world is that of Podley the innkeeper in Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door.

Podley is a Beanish, a species originating in the Beanbean Kingdom, the location of Mario & Luigi: Superstar Saga - a game not part of the Paper Mario series. In addition, Goombella mentions Chuckola Cola, a beverage produced only in the Beanbean Kingdom and nowhere else. If she is aware of it, then the Beanbean Kingdom exists, but as we have seen in Mario & Luigi: Superstar Saga, the Beanbean Kingdom and its denizens are not made of paper. Therefore, the paper presentation is either for the purposes of visuals only, or temporary at best.

In Paper Mario: Sticker Star, paper is much more than visuals.

Now it is not just the environment that is treated like paper during cutscenes, it's characters being treated like paper in story-relevant ways. The Toads tell Mario that Bowser "lined up their edges together" before stuffing them into the cabinet, meaning that characters are not only aware of being paper, but are also treated as such by other characters.

Of course, the environments have had the same principles applied to them, and are now fully and clearly made out of paper not just visually, but in terms of story, as well.

In short, the paperization of the series was complete by that point.

Paper Mario: Color Splash continued in exactly the same vein, and in fact did not add much (if only because the paper aspect was already saturating all elements of the world so much that adding "much" was impossible) except more elaboration on the idea of treating characters like paper objects; in particular, now living characters become "inert", inanimate paper by having had their color drained from them.

In the game's intro, a Toad in received in the mail, having been folded into a letter and stamped. Throughout the game, it is revealed many times that an object thought to be inanimate was simply a living being that had its color drained; and as almost everything in that world is now made of paper (except for a handful of realistic objects called "Things", the origins of which are never explained) any paper surface could be a living being, merely unpainted or painted the wrong color. One can only imagine this being rather disquieting to think about the implications of, but the game does not dwell on it too much and I do not specialize in theorizing beyond what is clearly shown on-screen.

Finally, Mario & Luigi: Paper Jam answers the question that has been building throughout the previous two games: how can the fact that the Paper Mario universe exists alongside the normal universe be reconciled with the new idea that everything in the Paper Mario universe has always been made out of paper, forever? It does so by simply declaring the first part to be no longer valid: the Paper Mario universe is not a part of the normal Mario universe, but a micro-universe inside a magic book within the latter.

In the game's intro, Luigi from the regular world accidentally releases characters from the paper world into the regular world. Paper Mario, Luigi, Peach, Bowser, Bowser Jr. and Kamek are also among the characters released, and them meeting their regular counterparts once and for all establishes that the Paper Mario world is not the regular Mario world.

Now, there is one open question about the book: does it contain a full copy of the regular Mario world, or merely the Mushroom Kingdom and a few other unique locations? We only see characters native to the Mushroom Kingdom (and Prism Island, which is a Paper Mario-exclusive location) in the three games that assert that the Paper Mario universe is different from the regular one, and we never get to see what is inside the book in Mario & Luigi: Paper Jam. Still, Goombella is referenced in Paper Mario: Sticker Star, meaning that she still exists in that universe, which in turn means her reference to Chuckola Cola should still be valid. In order for this to make sense, the only explanation is that the book contains a complete copy of the regular Mario world - but of course, we will have to see what the official explanation is once (or if) a new Paper Mario game is released.

In the end, we can see that the series went from something that did not even have "paper" in the name (and was in fact supposed to be a sequel to Super Mario RPG, although this was scrapped early in development), to a series that now fully asserts its paper theme by clearly delineating its universe as a magic micro-universe made out of paper within the larger Mario world. Who knows where the future will take us? Will "Paper Luigi" ever be released? We can only wait.

Mario and Dr. Mario: Same Person or Different Person?

Dr. Mario has long baffled players by being kept very separate from Mario's regular persona. Not only do no games featuring regular Mario ever mention him being a doctor in addition to his other jobs and adventures*, the Super Smash Bros. series also presents Dr. Mario as a completely different character from Mario. Let us examine everything official sources have to say on this matter.

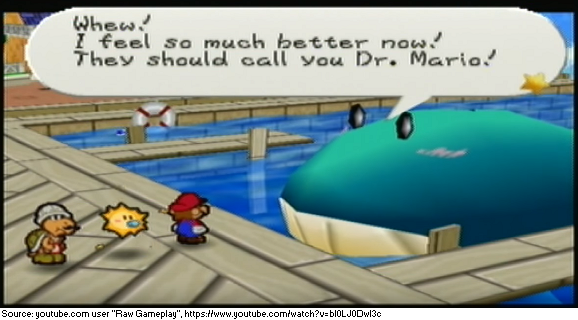

*On one occasion, the words "Dr. Mario" are spoken in Paper Mario, but not as a clear in-universe reference to Mario having an MD, but rather as a fourth-wall breaking reference after Mario heals a whale (note "they should" instead of acknowledging that Mario is already a doctor):

Let us start in the beginning. The manual for Dr. Mario on the NES, the first game in the series, lays out unmistakably that Dr. Mario is in fact Mario:

Mario acknowledges that it may not be believable that he is a doctor, but that he is one nevertheless. This alone is such strong evidence that we could declare the case closed right here - if not for the unfortunate fact that later official material seems to contradict it.

Dr. Mario 64 contains a story mode - one bizarrely involving Wario Land 3 characters - in which Dr. Mario is only ever referred to as Dr. Mario, and no mention of his other jobs is made. Still, in the manual we can find this:

In the third line, the manual calls Dr. Mario "Mario". Whether this is supposed to serve the same explanatory purpose as the original NES manual or whether it was a lapse on part of the editor is unclear.

In subsequent manuals, the story of Dr. Mario is simply never mentioned. It appears that Nintendo is intent on presenting Dr. Mario in his own, separate context - at least in his own games. What creates the most confusion around Dr. Mario's identity is his trophy descriptions in the Super Smash Bros. series.

This trophy description from Super Smash Bros. Melee states that Dr. Mario is slower than Mario due to his "lack of exercise". Now, a lack of exercise can not be acquired just by assuming another persona and changing your outfit, it is a statement about the entire lifestyle of the character in question - exercise carries over between personas no matter how separate. Since the description implies that Dr. Mario has a lack of exercise, but regular Mario does not, it is impossible for them to be the same character.

In Super Smash Bros. for Wii U, this is again reversed:

Now, the original story from the NES manual is referenced again. However...

The trophy immediately following the previous one again states that the differences between Mario and Dr. Mario are due to something that makes little sense if they were the same character - although this makes little sense either way: the description claims that Dr. Mario's MD is responsible for slowing him down. If this refers to some hypothetical kind of heavy diploma, or documentation, that Dr. Mario is forced to carry at all times, it could be understandable, but if it refers to the mere fact of having completed medical school, then it is probably not intended to be taken seriously.

Of course, Super Smash Bros. trophies are known to contradict information found in the game series those are from. Therefore, we can state with perhaps not full certainty, but with high confidence that Dr. Mario and Mario are the same character, at least according to games actually focused on Dr. Mario. However, if you would like to believe that Dr. Mario and Mario are separate characters, there is official content at least indirectly supporting it, so you may continue to do so, as well.

The Lost Fortress

The Prima Official Guide for Super Mario Galaxy contains a section featuring concept art for the game with commentary from the developers. One object showcased therein is this fortress:

Interestingly, model files for this fortress still exist in the code, along with some rudimentary textures. While the fortress looks only a fraction as detailed in its unused model, the parts that are present are remarkably similar to the concept art. Here are screenshots of the model, rotated into the same positions as the concept art:

(All further screenshots of the model use the same source as the above image.)

Note, among many other things, the absence of water, the complete omission of everything on the semicircular underside of the planet, the lack of trees and the missing minor details like the cords and flagpole. Although it is not entirely correct to say everything has been removed from the underside - merely everything visible in the concept art. There is actually one solitary object remaining there:

A Warp Pipe. Now, compare this Warp Pipe to the one on top of the highest building both in the model and in the concept art. They are in fact connected by a continuous pipe model - which does not occur in the finished game, but was later used in Super Mario 3D World for the "clear pipe" concept.

There are two other Warp Pipes in the model, also connected in the same way, see the green objects above and below the outcropping:

Here is a shot of the side of the planet not visible in the concept art:

Curiously, even though from a distance, it appears that the windows of the fortress are black holes, they all use this texture:

This is probably supposed to represent wooden shutters, but the texture admittedly looks a lot like a door, as well.

The shadowy object on the underside of the planet at first appears to be Megaleg, the first observatory dome boss in the finished game. However, this is not the case, as a model of a construct much more closely matching the concept art is also found in the code:

This is "BossCrab", an unused enemy and likely an early form of Megaleg, with four legs instead of three. It is somewhat curious how a boss like that could be fought on the planet without artificially restraining Mario to the underside: if Mario were to climb the fortress, would the boss follow? It would be extremely difficult to program the boss to climb such complex terrain without errors or glitches.

If you look very closely at the top left corner of the concept art image, you can see a planet with three trees and three platforms. This can also be found in the data; I have made a post about it on my main blog here.

Finally, let us look at the internal name of the fortress model itself. It is called "StarManFort". While the name itself does not seem to get across much - it could refer to "Starman", the Super Mario Bros. name for the Super Star item, or just stars in general, which are abundant in Super Mario Galaxy - it does tie this model in with two others.

The first is this one called "NeoStarManFort". Strangely, although the name seems to imply that this is a newer version of the fortress, the model seems much less detailed, with the buildings being replaced with generic platforms. Going off of the apparent state of the model, it could be an older version of the fortress, even though this is directly contradicted by the name.

The second model could answer the question of what "StarMan" refers to, being named "StarMan" in the code:

It is very likely that these were intended to be the inhabitants of the fortress, although whether they were friendly or hostile is not clear. According to tcrf.net user "Peardian", another model of the same character exists called "SpotLightEnemy", meaning both that it is an enemy and that one of its abilities would be to shine a spotlight. However, it could be that the SpotLightEnemy and the StarMan models were intended to be colored or textured differently in-engine, with one of them representing a friendly NPC and another an enemy, but sharing the same model (if you think this is unlikely, consider the exact same scenario happening in Super Mario 64 with hostile black Bob-ombs and friendly pink Bob-omb Buddies, who share the same model). In the end, we will never know unless Nintendo decided to release more information about the StarMan species.

I would also like to note that the guide contains another concept art for a planet with a similar concept to the fortress, but appearing as a much larger castle:

This is likely a very old concept of the fortress, probably one drawn without an intent to turn it directly into a model, as it lacks any gameplay-relevant imagery like Warp Pipes.

Quicker Squid

One of the boss fights in Super Paper Mario is against a giant Blooper at the end of Chapter 3-2. Quick aside: the music that plays during the Blooper's reveal (but not during the actual battle) is a reference to the underwater music from Super Mario Bros. 3. To defeat the Blooper, the player has to wait until a red tentacle comes up from the bottom of the screen, then attack it. Usually, several blue tentacles come up first, resulting in the player needing to spend time dodging them before getting a chance to counterattack.

However, a trick can be used to defeat the Blooper very quickly. Please take a look:

(Source)

If Mario flips to 3D next to one of the boundary-delineating yellow tentacles, all of the Blooper's other tentacles will rise from the bottom of the screen to build a wall of tentacles - including the vulnerable red tentacle. This allows Bowser's fiery breath to hit the tentacle upon switching back to 2D, as now all tentacles are layered on top of each other.

Strangely, there seems to be little point to the Blooper raising all tentacles to bar Mario's way in 3D, as the yellow tentacle is programmed to always move in such a way that it is in front of Mario, and even if the yellow tentacle is passed, an invisible wall is present just behind it. Thus, the raising of the tentacles is purely to provide a visual effect, which is then exploited to quickly defeat the boss.

Hidden Debug Mode in Wario Land

Wario Land: Super Mario Land 3 is one of the very few Mario games with a debug mode that is accessible not only by modifying the game's code, but during normal gameplay without much issue. Simply pause the game and press Select 16 times to bring up a small square cursor over the status bar.

The cursor can be moved left and right by holding B and pressing Left and Right. Whenever it is on a digit, pressing Up or Down increments or decrements that digit, respectively. This can be used to give Wario up to 99 lives, 999 coins, 99 Hearts and 999 time units. By holding A and B and pressing Left when the cursor is on the tens digit of the lives, the cursor will move to Wario's head. Unpausing at that moment will result in Wario changing his state - cycling through Small Wario, normal Wario, Bull Wario, Jet Wario, and Dragon Wario before going back to Small Wario. This debug mode is relatively well-known.

What is less well-known, however, is the second debug mode of the game, which can in fact only be activated by modifying the code, or using Game Genie code 018-C75-E6A. This debug mode is more extensive, containing not only all features of the regular debug mode, but also several exclusive ones.

The first feature encountered when activating this debug mode is that courses do not start automatically upon selecting them from the map screen. Instead, a menu appears where a course can be selected from among every valid course in the game by pressing Up or Down. The course's in-game number appears in the center, while its internal number appears in the lower right. The internal numbers range from 00 to 2A (hexadecimal for "42") for a total of 43 levels. Some courses have two states and appear as two internal numbers, such as Course No.01 being index number 07 in its non-flooded state and 17 in its flooded state.

After entering a course, you will discover that the state-changing feature, previously available by selecting Wario's head in the regular debug menu, has now been mapped to the Select button, making it easy to power-up Wario on the fly. In fact, with this feature is it almost impossible to die to anything except instant-death obstacles, as simply pressing Select after Wario is hit instantly reverts him to a state where he will not lose a life after another hit.

The most important feature of the hidden debug mode is the free-roaming mode. To enter it, simply press Start, then Select. Wario can be moved around freely in 2D space while the game is paused, and unpausing it will deposit Wario onto the spot he is overlapping. The mode is surprisingly stable; while usually free-roaming debugs allow the player to scroll the camera past the boundaries into a non-playable area filled with unset tiles that appear as a chaotic mess of unrelated graphics, this free-roaming mode simply does not scroll the camera outside of the boundaries. To make Wario enter a different area, it is possible to move him off-screen and unpause; if the position is valid, the camera will follow - and if not, Wario will remain off-screen.

Another feature of the free-roaming mode is that it is not possible to move Wario below the death barrier. When Wario hits the death barrier in this mode, he will assume his death animation and die when the game is unpaused, even if he is moved to another place beforehand. (See above footage for example.) However, it is sometimes possible to cause the mode to become glitched by moving Wario again several times after he had died, as the game allows pausing even in the middle of the death animation.

This results in Wario becoming controllable again, but the sprite of his hat, which detaches as part of the death animation, persists and continues falling, looping when it reaches the bottom of the screen:

The falling hat will follow Wario through the level and continue falling even in free-roaming mode.

Finally, an interesting observation about the way the game handles bosses can be made using the debug mode:

By using the free-roaming mode inside a boss battle, the graphics become glitched the moment Wario attempts to leave the screen. This causes previously transparent tiles to become filled in, revealing that in order to move around large objects like the Genie boss, the entire background moves. In other words, the Genie is not a sprite that moves relative to the background, it is itself the background, and uses background scrolling to move. This is very common in older games, but seeing it visualized like this is still worthy of note.

Bomb Hat Connection

This is less of a fact and more of an observation, which may stem from a cultural common source I am not aware of - if you have more information on this, please contact me over Patreon and I will edit this section to include it.

This is a Poppy Bros. Jr.* enemy from Kirby Super Star:

*(Unlike the Hammer Bros and all related Bro species in the Mario series, whose name's singular form is "Bro", Poppy Bros. Jr. still contains "Bros." in the singular form.)

The Poppy Bros. Jr. is a staple enemy in the Kirby series. Note that he wears a specific hat - a night cap with a white brim and a white ball or pom-pom at the end. Note also that he uses bombs. These two are the most important traits of that enemy.

Now take a look at the Sprite from the SNES version of Wario's Woods:

Appropriately enough given the name, the Sprite exists only as a sprite; i.e. there is no official artwork of it. The entire situation surrounding official artwork for Wario's Woods is highly odd; even though Birdo, the Sprite and the Pidgit that summons enemies are very important to gameplay, and at least the former two also important to the story according to the manual, neither of them have any official art. Instead, all artwork is of Toad, Wario, the enemies and the bosses.

That aside, the Sprite has the same night cap with a white brim and pom-pom as the Poppy Bros. Jr., and it also does nothing but produce bombs. Of course, I am not implying that there is any kind of connection here - the Sprite, being a type of fairy, could simply be wearing a cap that is associated with those kinds of magical beings (elves in particular), and the fact that it is summoning bombs has no story relevance and exists only as an excuse to enable the gameplay.

Still, when I first realized the connection, I wondered if both of these characters were a reference to something else, perhaps from Japanese folklore. Is there an elf-like creature that wears a nightcap of this kind and uses bombs that both of these are based on? If you have any thoughts on this matter, please let me know!

Gunyolk's Eyes

If you have played Super Mario RPG all the way through until the end, you may remember this fight right before the final boss:

The enemy in the top right corner is Gunyolk, one of the creations of Smithy's factory and the final encounter before the battle with Smithy himself. Gunyolk appears as a grey machine resembling a tank, containing a vat of orange liquid. During some attacks, the liquid comes to life and assumes a form similar to Roger the Potted Ghost from Yoshi's Island:

However, due to the game's very stark shading on its pre-rendered character sprites and the relatively high amount of detail that needed to be compressed into low-resolution images, it is not easy to see that Gunyolk's metal body has eyes as well:

In the official art, we can see that Gunyolk has angry, semicircular eyes to the left and right of the lower front cannon. These are hard to recognize as eyes due to using the exact same "steel with rivets" texture as the rest of the enemy.

This is not the only time the game's official artwork is hard to decipher - the following example has been a point of contention ever since the game's release:

Is Jonathan "Johnny" Jones a shark with a flat grey eye and a strange glowing yellow tongue, or a fish wearing a shark mascot costume head with a glowing yellow eye? Note that the "pupil" of the eye lines up perfectly with one of the teeth, meaning that it could be the silhouette of a tooth in front of a glowing circle, and not an actual eye. Neither of the two interpretations seem completely logical, and no official answer has been given from Nintendo or Square.

Now Listen, All You Boys And Girls

(special thanks to twitter.com user "NishiOxnard" for the information)

If you have purchased the physical version of Super Mario Odyssey, you may have noticed the inside of the box containing lyrics for the song "Jump Up, Super Star!":

(Please excuse the bad quality; I was forced to take a picture of my own copy myself and I do not own any equipment that would let me take a better-quality photograph.)

And if you have been following the game's development from the beginning, you may remember that the song has a verse that starts with "Now listen, all you boys and girls" - which was heard on a loop during Nintendo's 2017 E3 presentation on the Nintendo Treehouse livestream. However, if you look at the above picture, the verse is nowhere to be found. In fact, it can't be found in the game at all. Listen to the first four minutes of the New Donk City Festival song (as it is called in-game). At the end, you will hear the song loop, but the verse will not have been sung.

In contrast, here is the version you may be remembering from E3 2017. The verse is present, and starts at 3:23. It is not known why it was cut from the game, as it is highly unlikely that it was recorded separately after the rest of the song. It is odd to think that one of Super Mario Odyssey's biggest assets used to promote it in advertisements, trailers etc. can be only found in its full form online, and not within the game itself.

This concludes this week's Supper Mario Broth: The Lost Levels. Thank you once again for your support. I must again point out that you are entitled to a refund, and note that due to the large delay in this week's work, the podcast episode for Broth Siblings may be delayed by up to 2 days and the next The Lost Levels article by up to 1 day. After that, however, I should be able to resume the regular schedule again. Please join me next week for Issue 7, featuring such topics as:

- Which Games in the Mario Franchise Have the Fewest Humans?

- Interpreting Tiny Maps

- Lose Extra Hard to See This Content

Thank you very much for reading.