Historical Underwater Habitat Showcase, Part 4: Continental Shelf Station Three (Patreon)

Content

The last two articles in this series covered Conshelf 1 and 2, so of course now I have to move on to the final habitat project ever undertaken by Jacques Cousteau. That's right bitches, it's time for Conshelf 3, the biggest and baddest of them all.

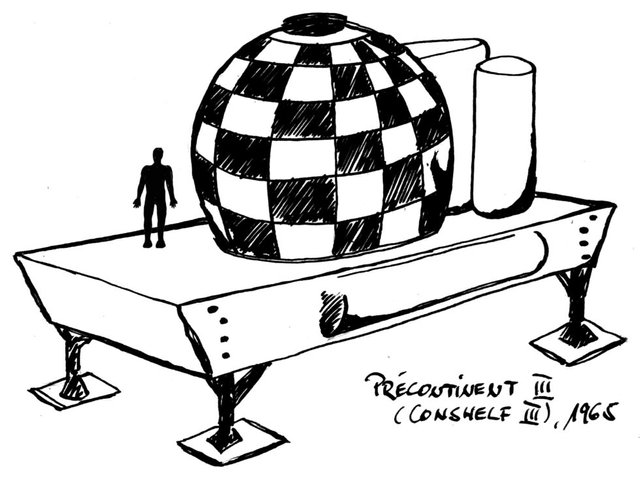

If it looks less beautiful and fantasy-esque than Conshelf 2, it's because Conshelf 2 was intended to be beautiful and a showpiece for the documentary about it. Conshelf 3, instead, was all business. Specifically it was a prototype for an underwater oil rig.

Funded entirely by the French petrochemical industry, Conshelf 3 was the first serious attempt to demonstrate the feasibility of putting humans underwater, long term, for the purpose of oil extraction. This was before robotics was advanced enough that ROVs could replace divers for most oil related tasks.

This was also before Cousteau had his environmentalist awakening, after which he did a 180 on the topic of human settlement of the sea, instead proclaiming we should stay out of the ocean and focus on conserving its biological diversity.

Imagine the consternation of his wealthy financiers when he did this. In all likelihood this was the turning point where they began looking for other ways than Cousteau's habitat technology to extract undersea oil deposits.

Of course today, the "habitat" is on the deck of the ship (the deco chamber) and the divers are shuttled between it and the work site by a pressurized diving chamber. More on that later.

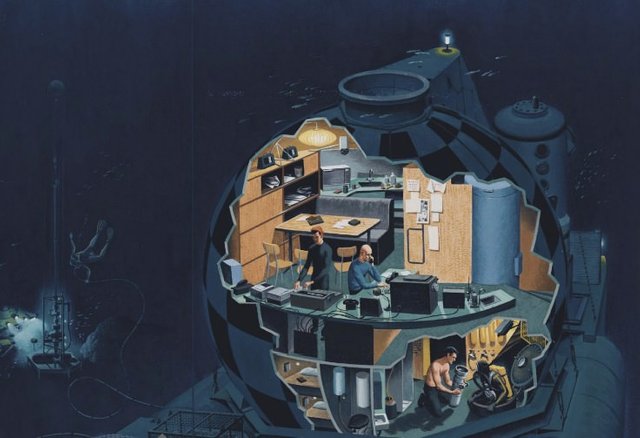

Conshelf 3 was deployed on September 17, 1965. It was emplaced on the sea bed at a depth of 100 meters, three times the depth of Conshelf 2. The habitable portion consisted of a sphere 15 meters across divided into two floors, roughly as spacious as Starfish House before it.

Because of the spherical hull, Conshelf 3 could be sealed up and used as a decompression chamber. It also had its own ballast tanks and so could lift itself up off the sea bed and float to the surface for relocation as desired, an important feature for a structure originally intended for oil extraction. When the deposit is depleted, the entire habitat would relocate.

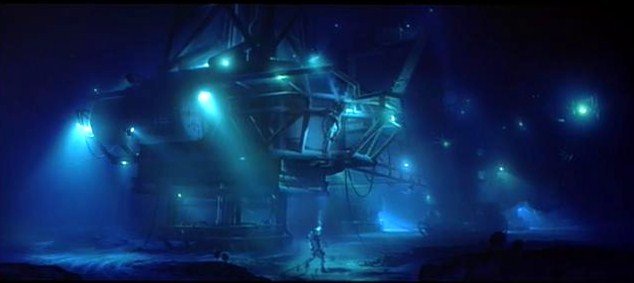

What a shame that didn't become the standard. Instead, as mentioned before, the way it's done today is for aquanauts to descend to the work site in a pressurized diving chamber which serves as their base of operations for each 12 hour work period. (Seen above)

When they are finished for the day, they climb back inside, seal it and the chamber maintains the pressure they are adapted to on the way back up to the ship. If 12 hours of labor at the bottom of the sea sounds dangerous and miserable to you, it is. That's why it pays famously well.

Once at the surface, the diving chamber is carefully docked to the shipside decompression chamber, as a crew capsule docks to the ISS. The deco chamber also has the higher air pressure inside they became acclimated to while working at depth. Here, they can relax and wait out the many hours of decompression necessary before they can safely exit the chamber.

Had things gone differently between Cousteau and his backers, perhaps we'd live in a different world today. One where entire submersible oil rigs sit on the sea bed, populated by crews of aquanaut oil workers living and working at depth for weeks, or even months at a time:

source

Stay tuned for subsequent entries in this series, the best is yet to come!